Picton to Opua via Napier and the East Cape (duh, duh, duh)

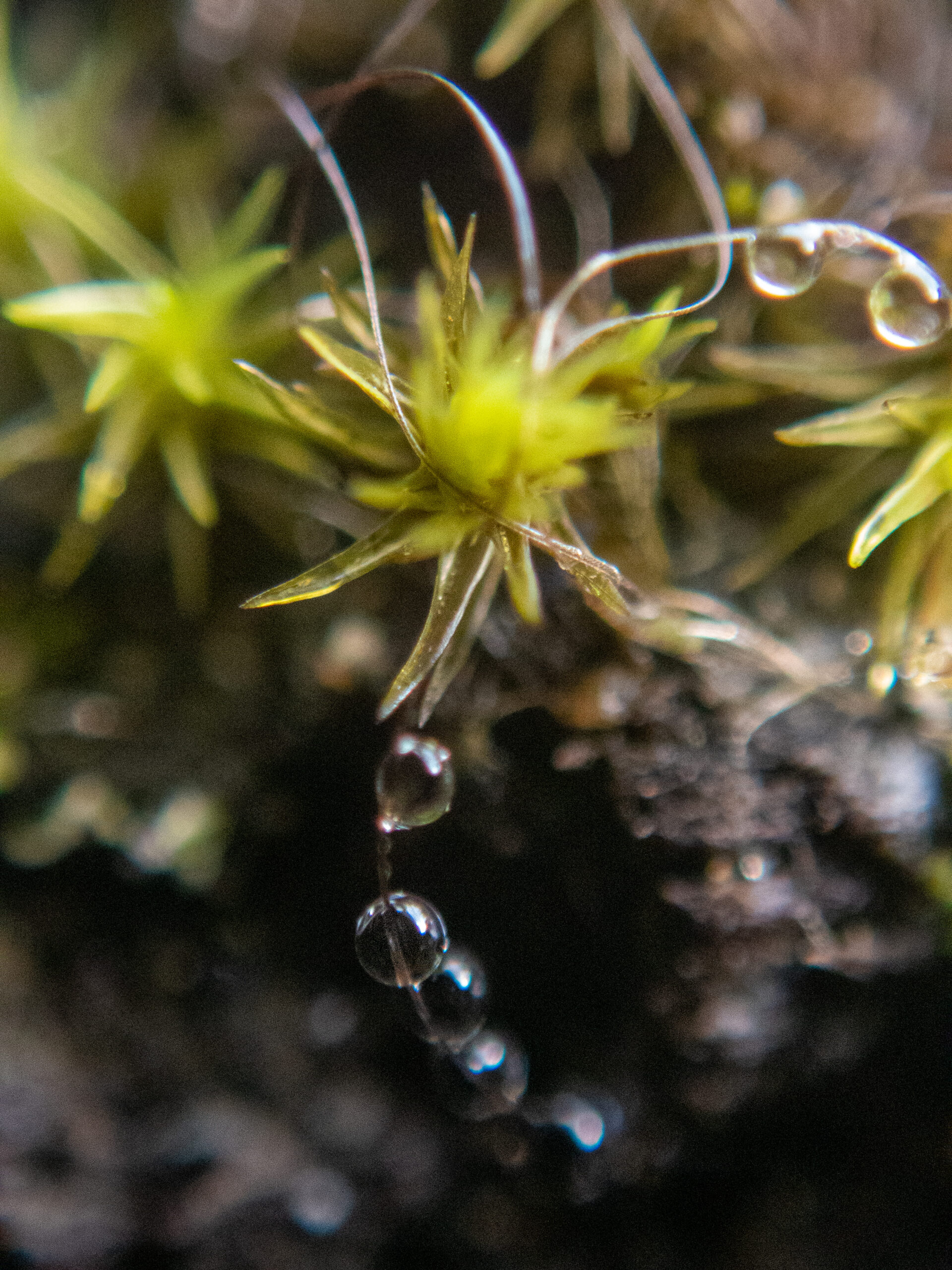

Diana’s last log entry on the first leg of this passage: “worst passage ever.” Maybe, I’m not sure, but I confess to getting seasick, for only the third time ever. Even so, I think the hardest part was leaving the South Island in dead calm with the threat of drizzle. After two and half years, it felt like leaving home, not least because we were leaving Haley and Liam, and knew it would be a while before we could get back.

Fueling up, (which for some reason is always a little stressful for me), was extra stressful knowing it was the last thing to do before saying goodbye. After multiple hugs and lots of tears, there was nothing to do but cast off the lines and pull away.

We were on a bit of schedule, running out of time to get to Opua before Maddi arrived from the States. Also, it was crucial to time our exit from the Tory Channel for a reasonably favorable current, the basic recommendation was leave on high tide out of Picton. We led that by an hour or two to try to avoid encountering head winds in Cook Strait. It was pretty mild to start and Diana made some super yummy wraps for lunch (she is the undisputed Empress of wraps in my book). As seems to so often be the case sailing around New Zealand, there was no chance of entirely missing the wind shift, and about halfway across we were sailing close-hauled. At least the seas, at that point weren’t too bad, not stacking up against current or anything. I went down to take a nap, and missed Diana logging 13 knots surfing on seas that were getting pretty steep. In fact, we wandered into the edge of an area of rip tides and overfalls, ‘Korori Rip,’ that was pretty dramatic. As it got dark the wind was on our beam and so were the steep seas. Diana was feeling pretty awful, and then I got sick too. This might have been where Diana logged “worst watch ever,” – she was really feeling bad and then the rudder on the hydrovane (our wind vane steering system) came off and started pounding on the stern. It took Diana a couple minutes to figure out what was going on, what the loud noise was. I donned a PFD, clipped the harness in and took a knife out onto the swimstep, hoping that I could cut the safety line off without losing it. It was pretty wet, but I didn’t want to take time to put on boots, so I opted for bare feet. Anyway, it actually wasn’t that bad, Diana has set up holder for a good sharp dive knife and a pair of pliers under the lid of the lazarette where they are super handy (she’s pretty good at coming up with that kinda stuff). I took the next watch and Diana tried to sleep off her seasickness. Once we cleared Cape Palliser things improved dramatically.

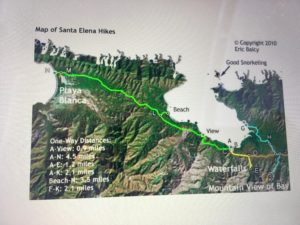

No doubt timing arrivals, departures, capes and channel entrances can be the trickiest part of sailing. You’re always trading one ideal for another. The next challenge of this passage was the East Cape, which is massive and takes a couple days to fully round. The forecast was for 4 meter seas and forty knot gusts… not super inviting. We liked better the sound of a snug marina slip at Napier to wait for the weather to ease up a bit, but that meant arriving at midnight, which is something we are loathe to do if we’re not really familiar with the layout. It’s never nice to feel like your options are bad or worse. As it turned out, the wind in the harbor was still and the passage in, though shallow, was well marked and very well lit. We glided to the visitor’s berth next to the travel-lift, easy peasy. The quiet and calm felt glorious.

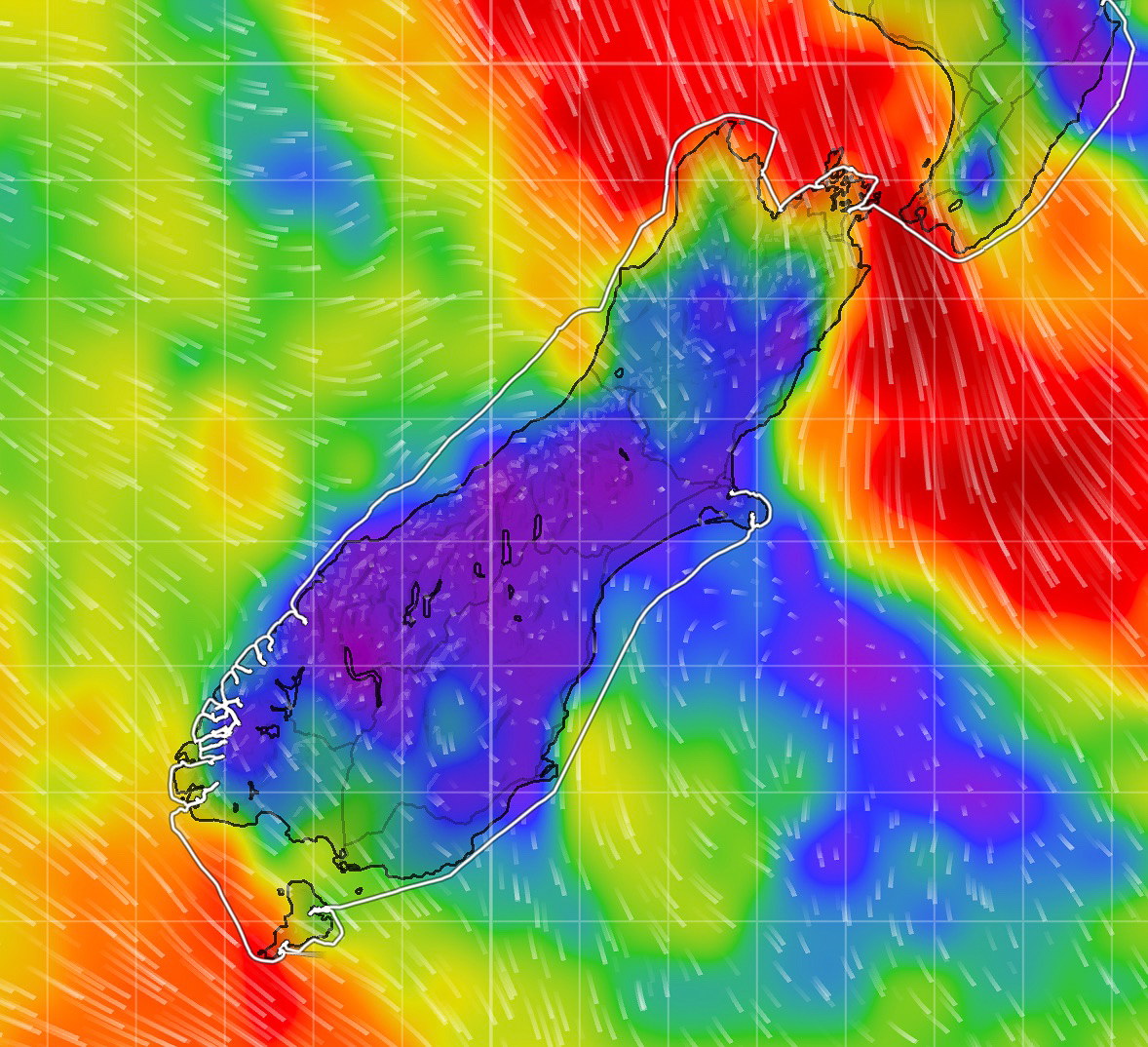

Waiting for the gale at the East Cape to ease came with a trade off — the near certainty that we would have to pass through a frontal system to reach Cape Brett. Yeah, I know, a lot of fretting about capes, but there’s a reason so many of them are given awful names by sailors (Cape Fear, Cape Runaway, Punto Malo, Cape Foulwind), they really do run the show. In the meantime, that lay two days in the future. We rounded the East Cape in the early morning, jibed and then enjoyed a glorious daytime sail headed northwest, pretty as you please, even got the guitars out for a little music.

The squalls started with darkness (naturally). Note to self: frontal passages are not to be taken lightly! Also I’m going to try to remember that the forecasts don’t really represent true wind speeds in these conditions. These are more like what you get with squalls in the tropics (sudden doubling of wind speeds) but over a much more sustained area and time period. Soon we were double reefed on main and jib, taking big seas over the whole boat.

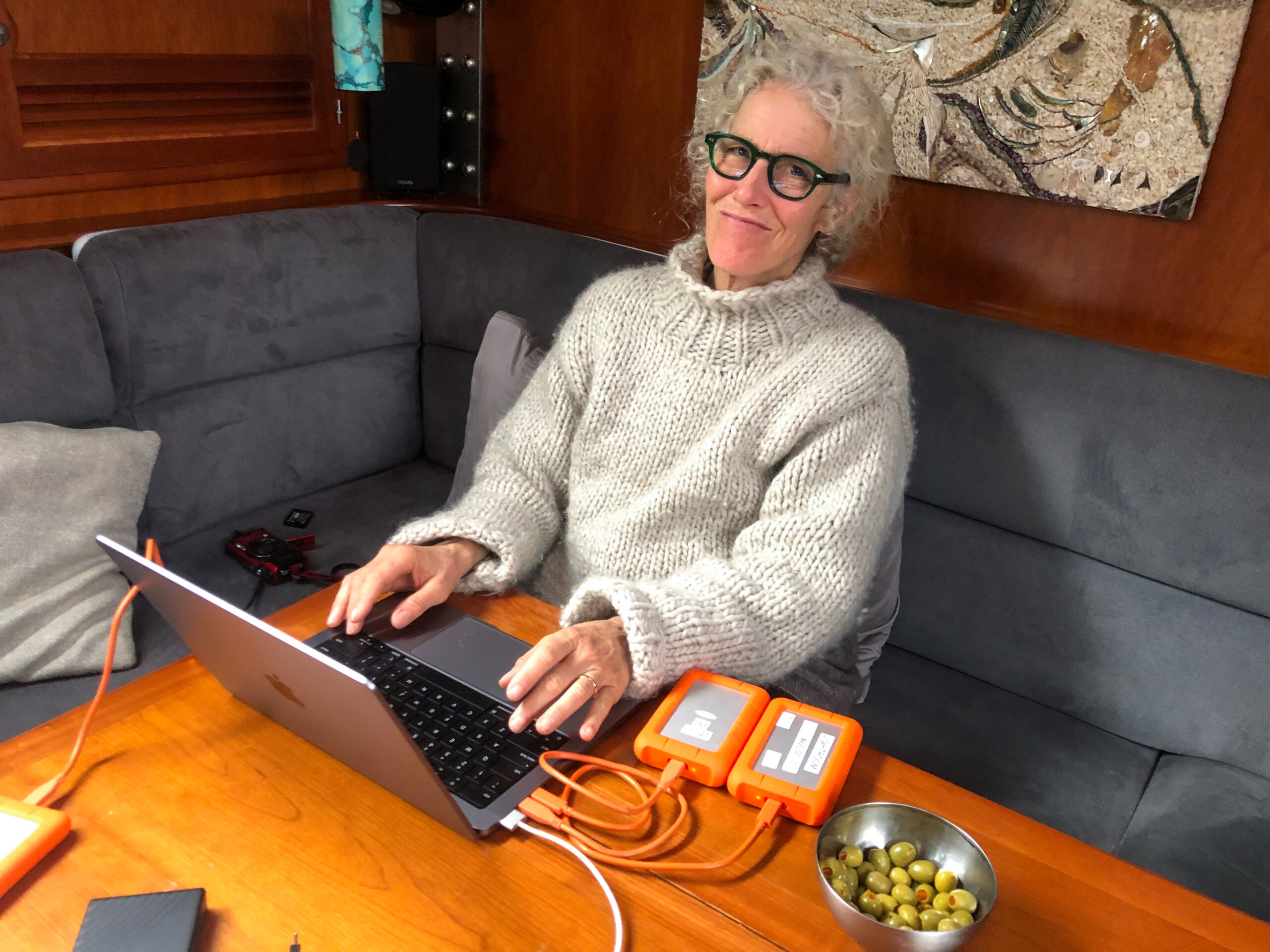

Once again, Diana took the hardest watch (you might accuse me of scheming here, but I swear this is just a matter of chance). Her words from the log: waves over bow, raucous, deluge, still dumping. Mine: rain, clearing, wind finally calming. At least I tried to make up for it giving her a longer watch off, putting in four hours to clear Cape Brett. All the while looking forward to the forecast easing and a swing of the wind for a quiet sail into the Bay of Islands. No such luck. Wind died, and then the engine died, 8X according to Diana’s notes. At 5AM I was back on, and eventually the mystery of the engine was solved. I was so focused on the last engine issue back in Fiordland (which was entirely electrical) that it took me a while to realize that the current problem was oil pressure. I’d checked the oil, but with a heeling boat, the reading was off. I added oil and the engine was happy again. More engineering-inclined-sailors than I have expressed skepticism about black boxes (computers) on marine diesel engines, but for the less mechanically minded (yours truly) they can actually be a life saver. Better the engine shut itself down than damage something, though it’d be kinda nice if the $1000 panel offered something a little more elucidating than “CHK ENG.”

Dawn came quietly, and it worried me a little to see fog along the coast, but it dissipated as we arrived, and pulled into a quiet slip in the Bay of Islands Marina. ~MS

" data-envira-height="475" data-envira-width="570" />

" data-envira-height="475" data-envira-width="570" />

" data-envira-height="480" data-envira-width="570" />

" data-envira-height="480" data-envira-width="570" />

" data-envira-height="428" data-envira-width="570" />

" data-envira-height="428" data-envira-width="570" />

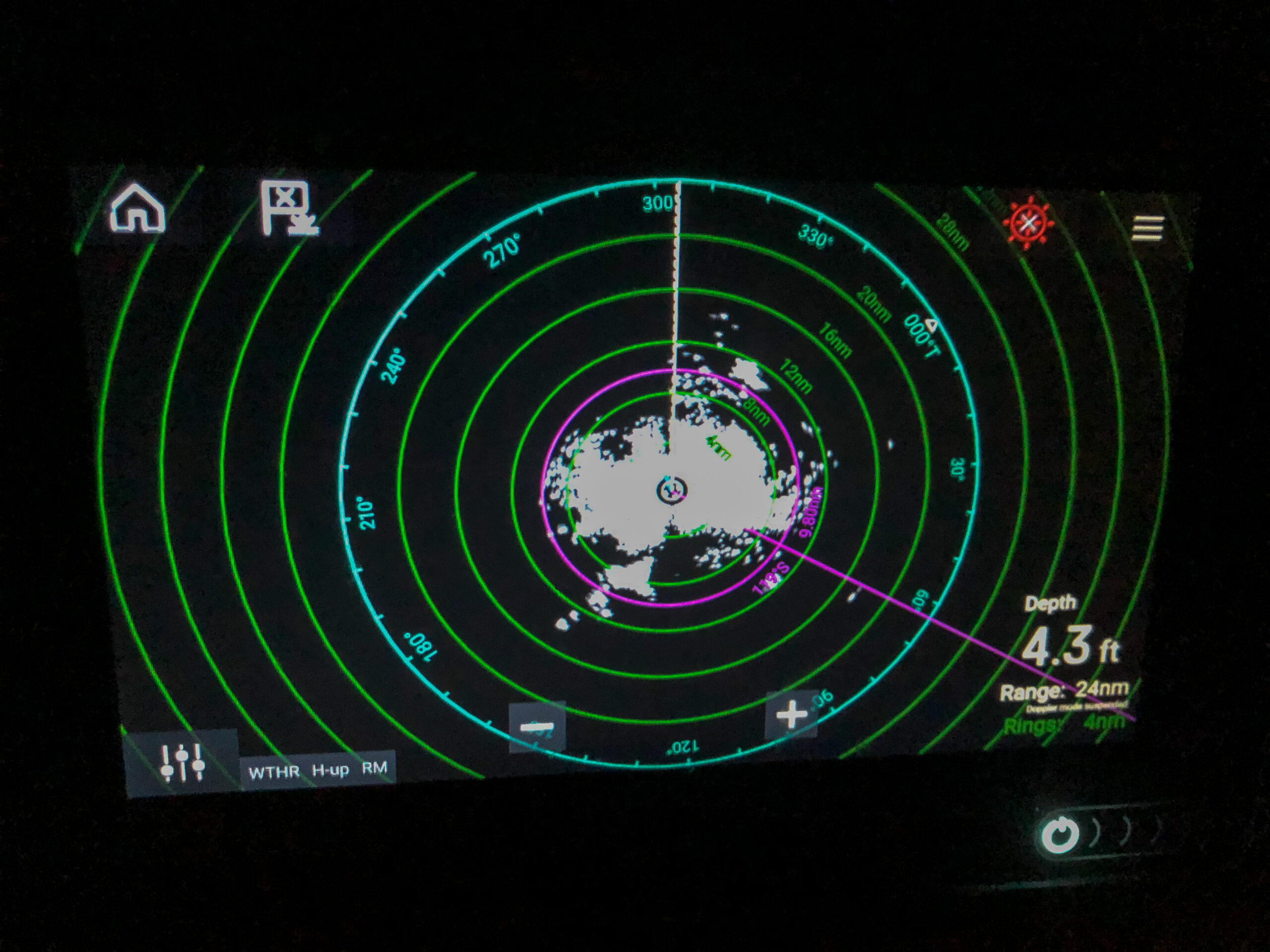

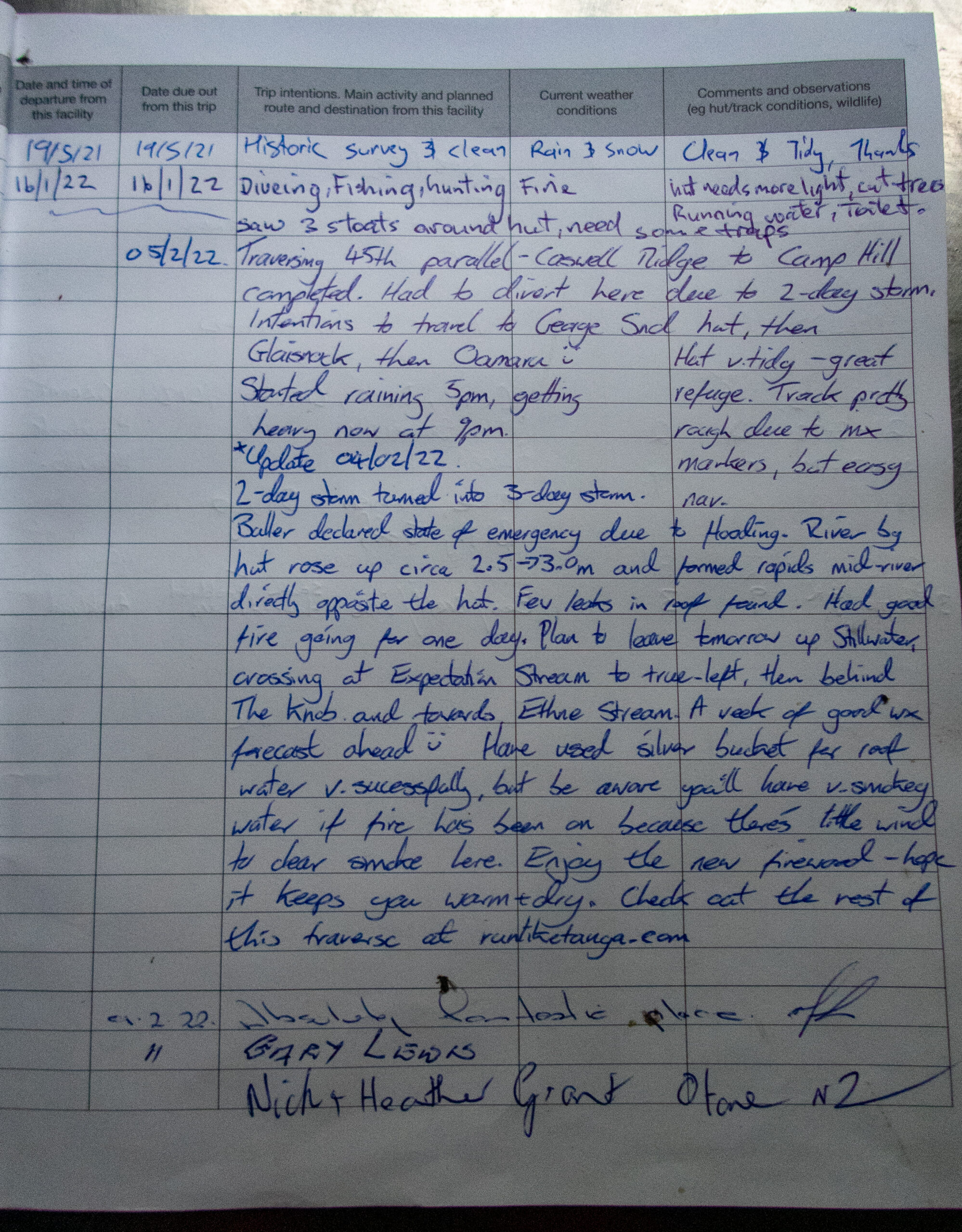

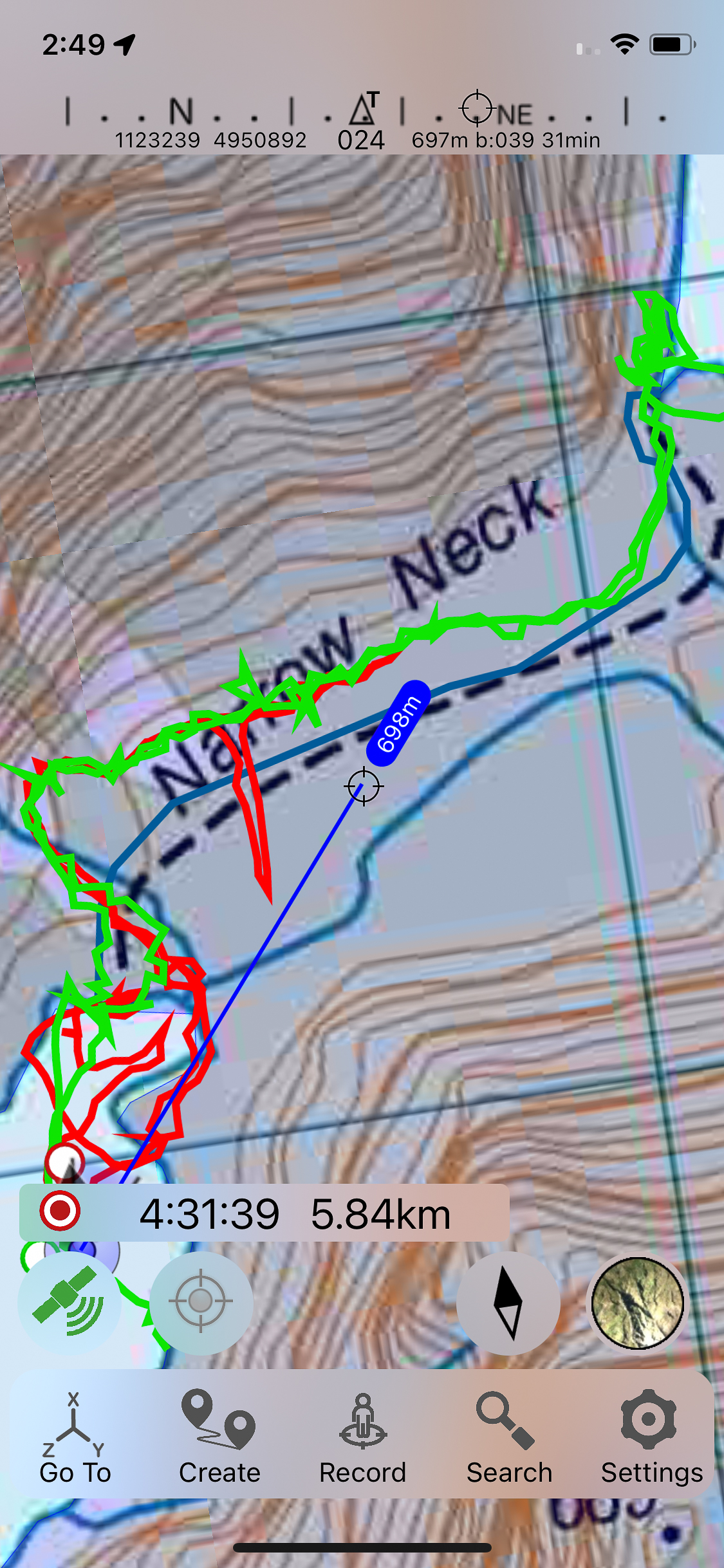

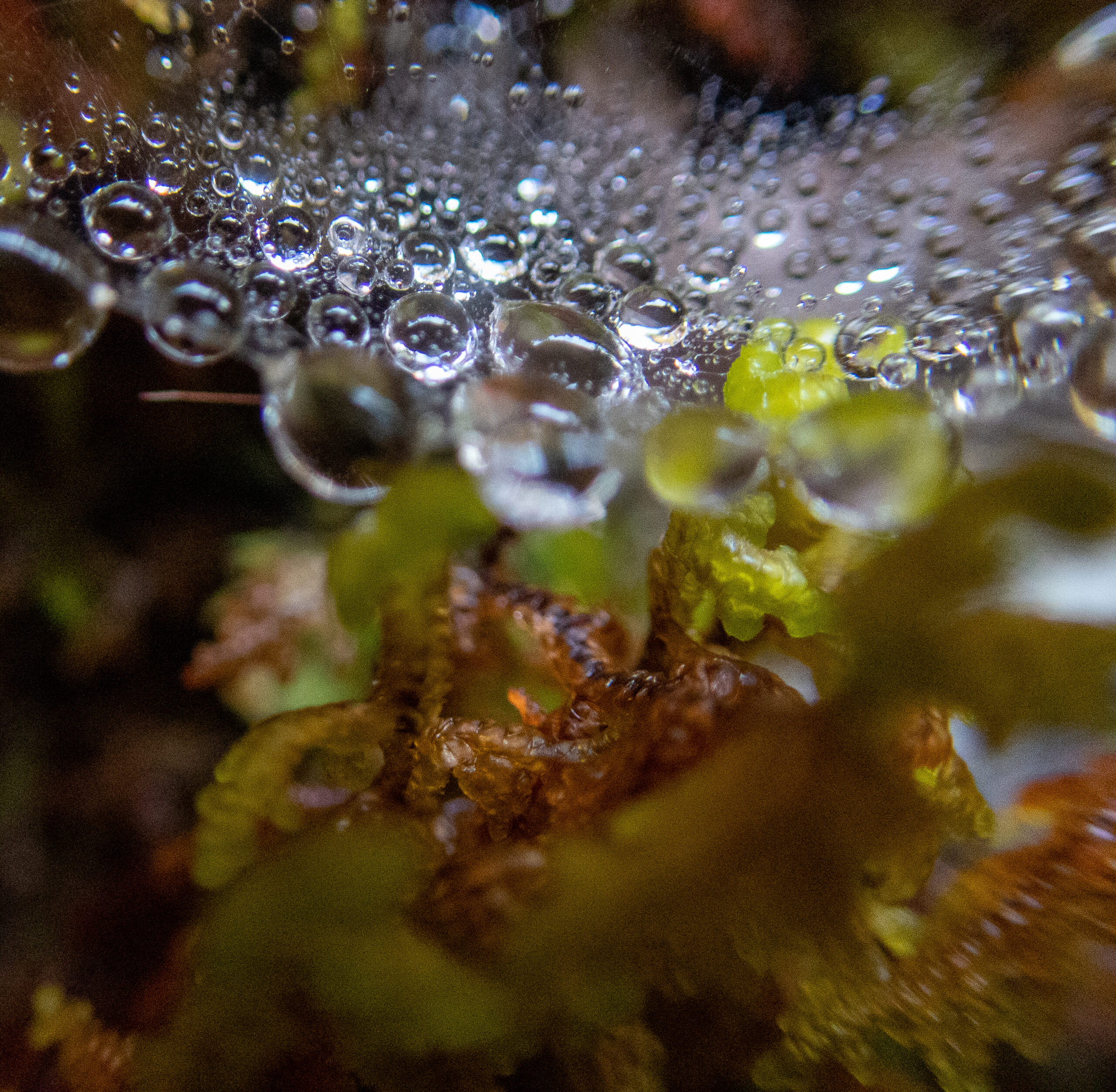

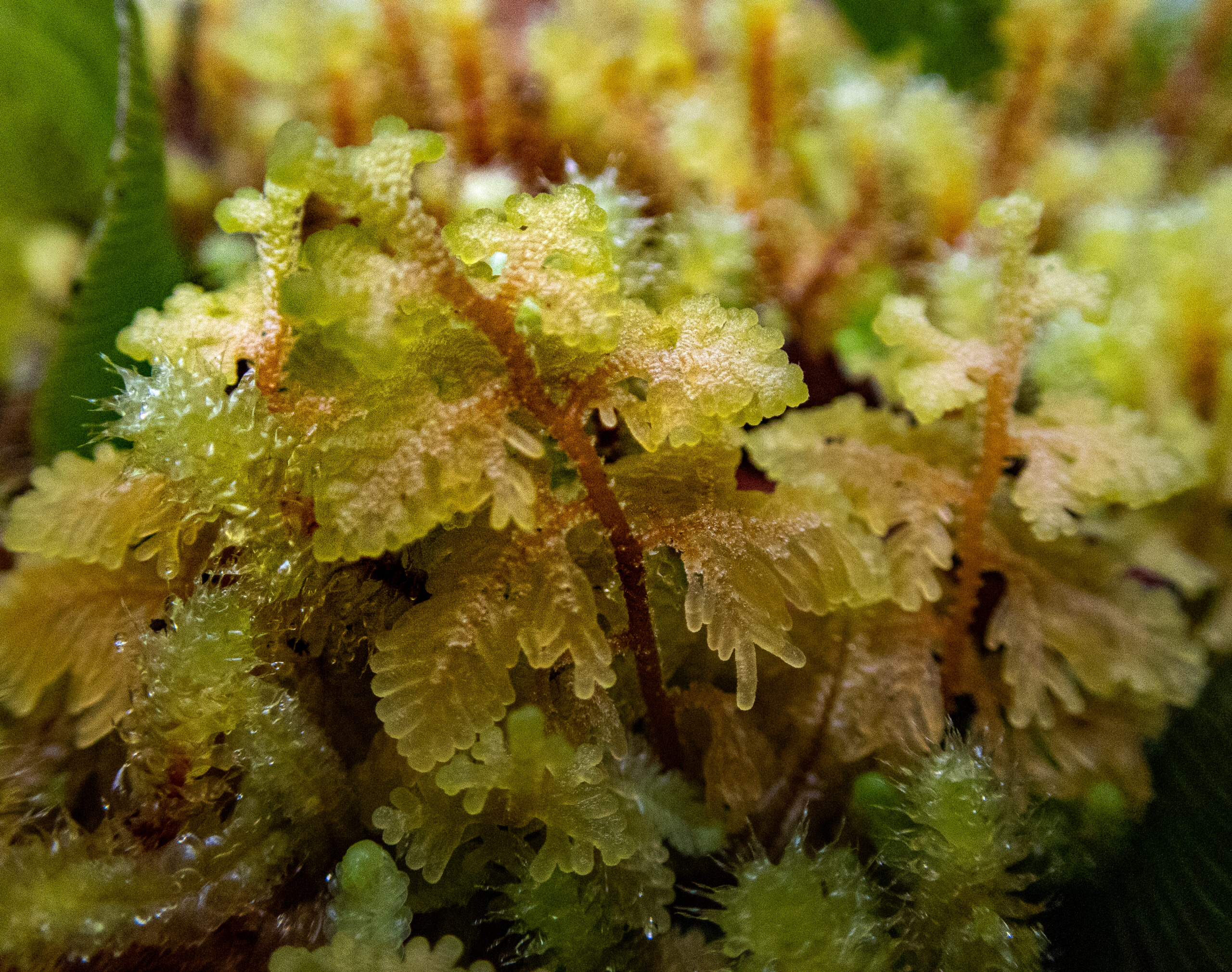

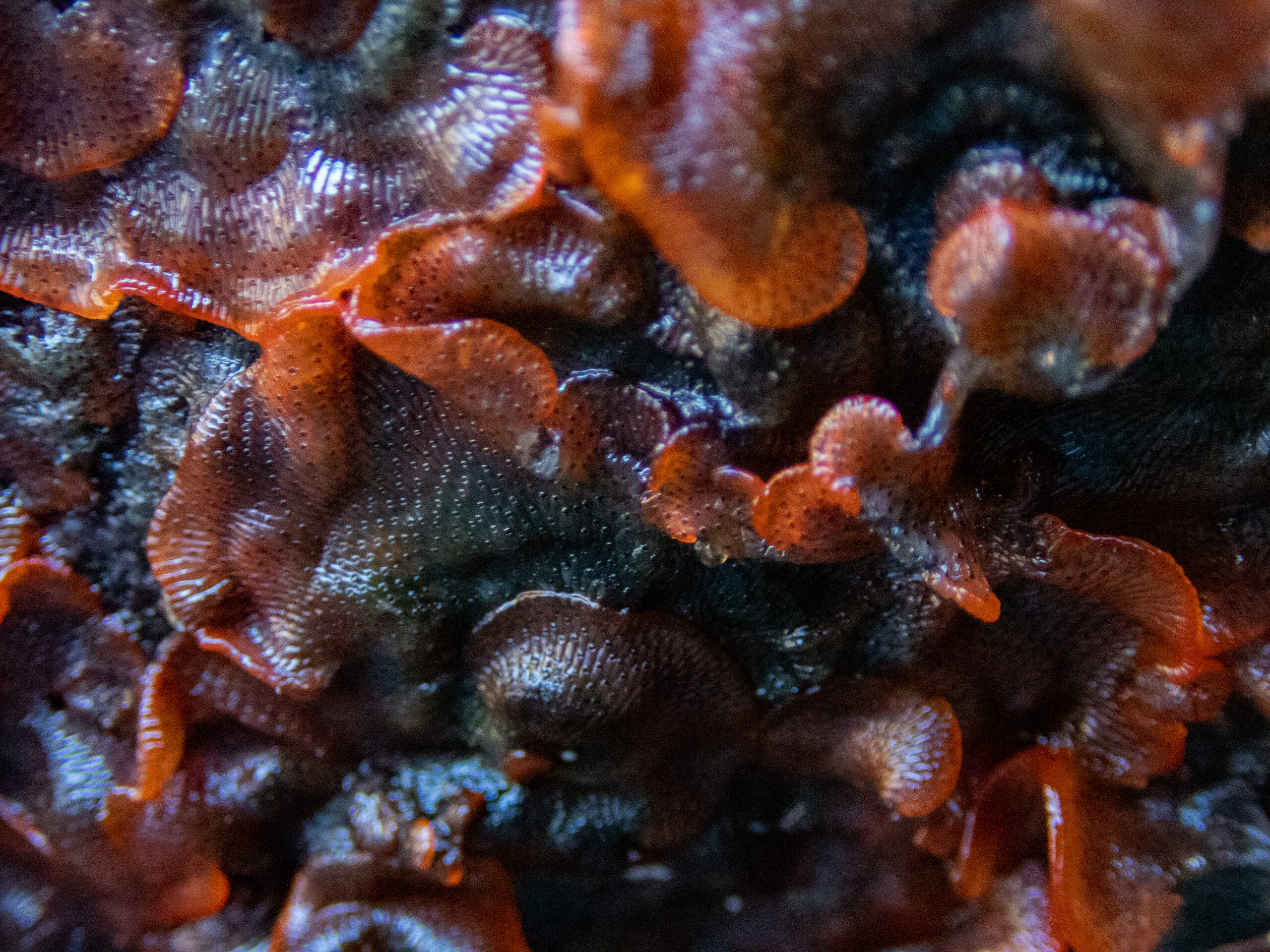

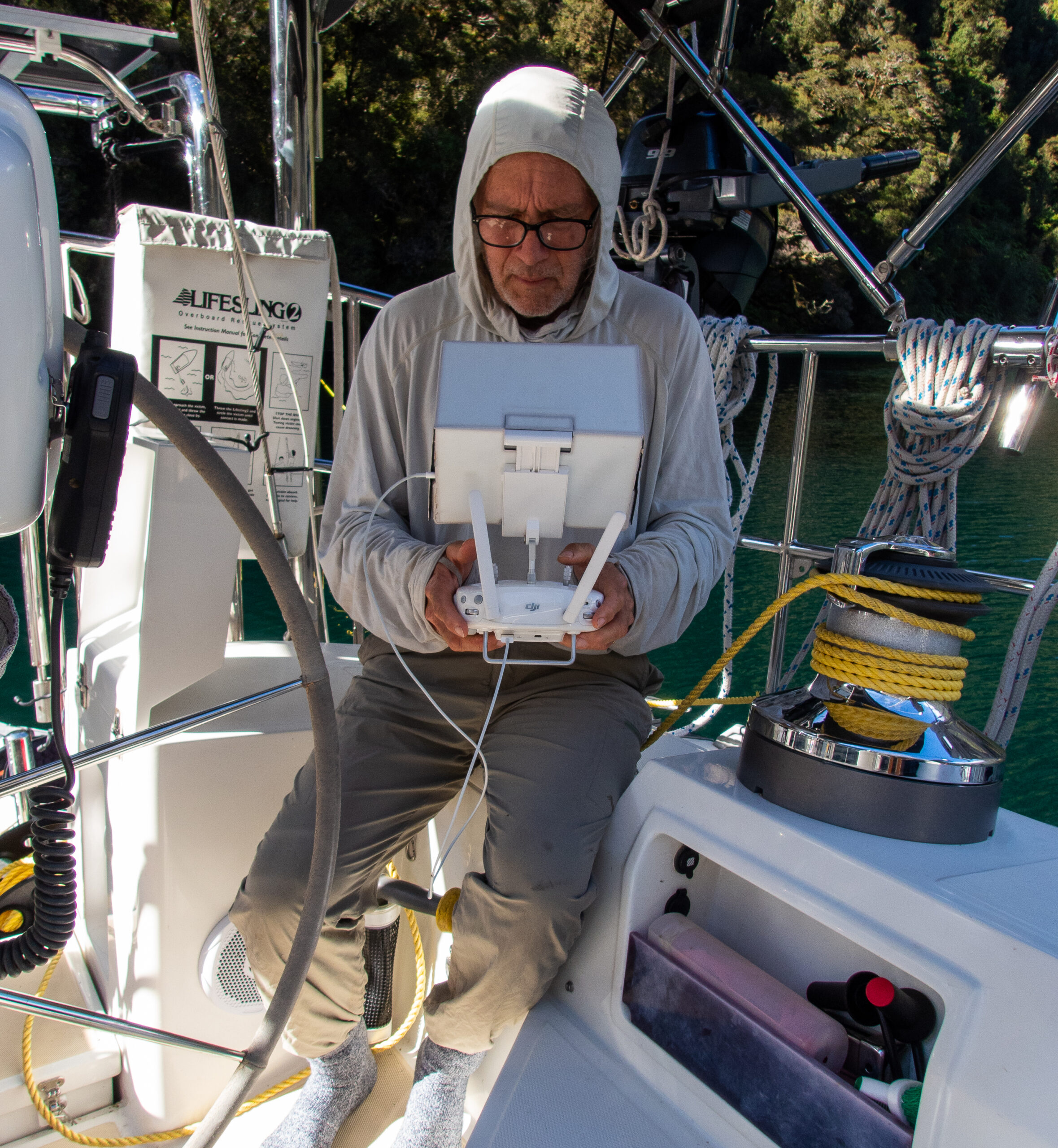

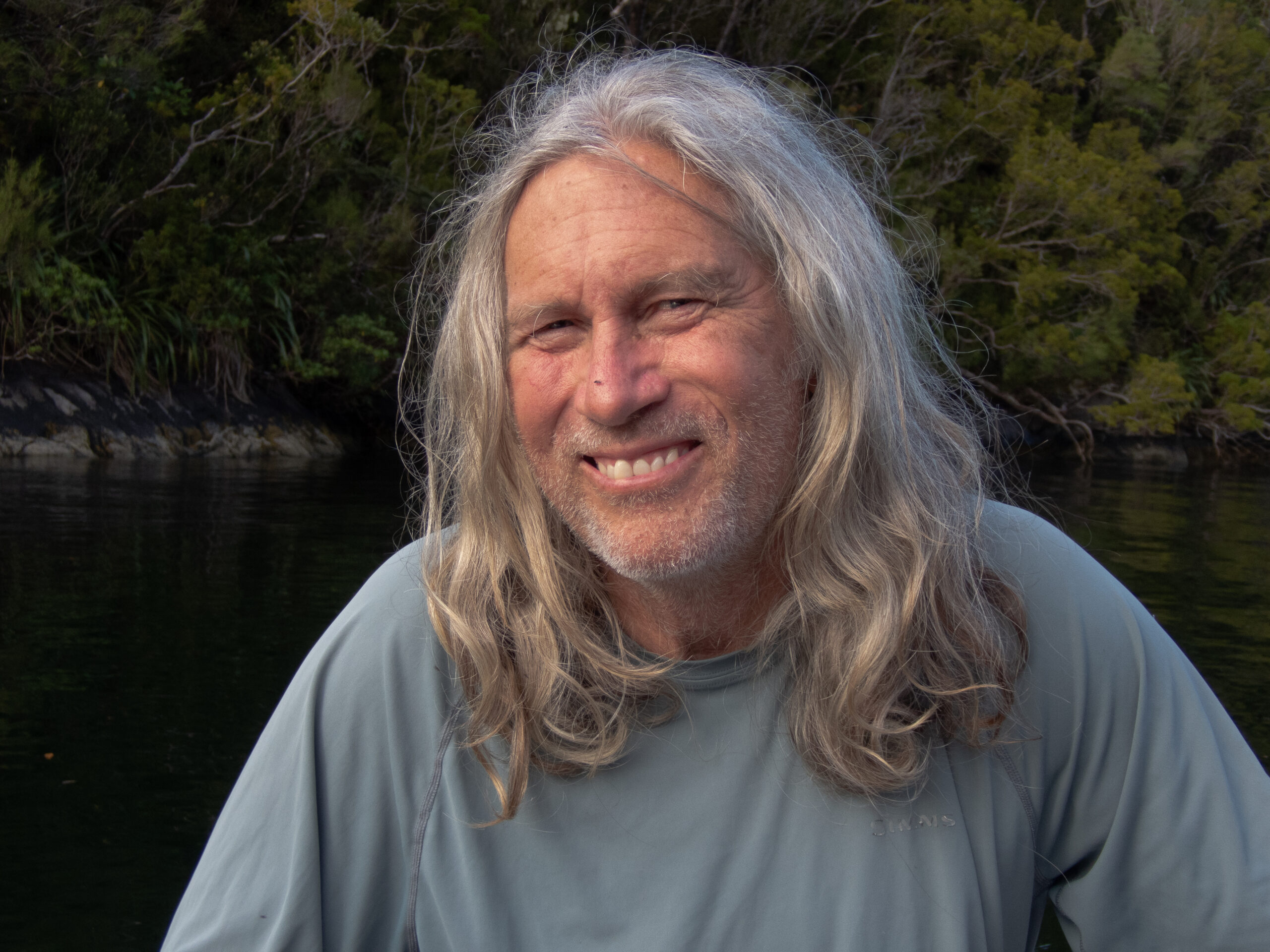

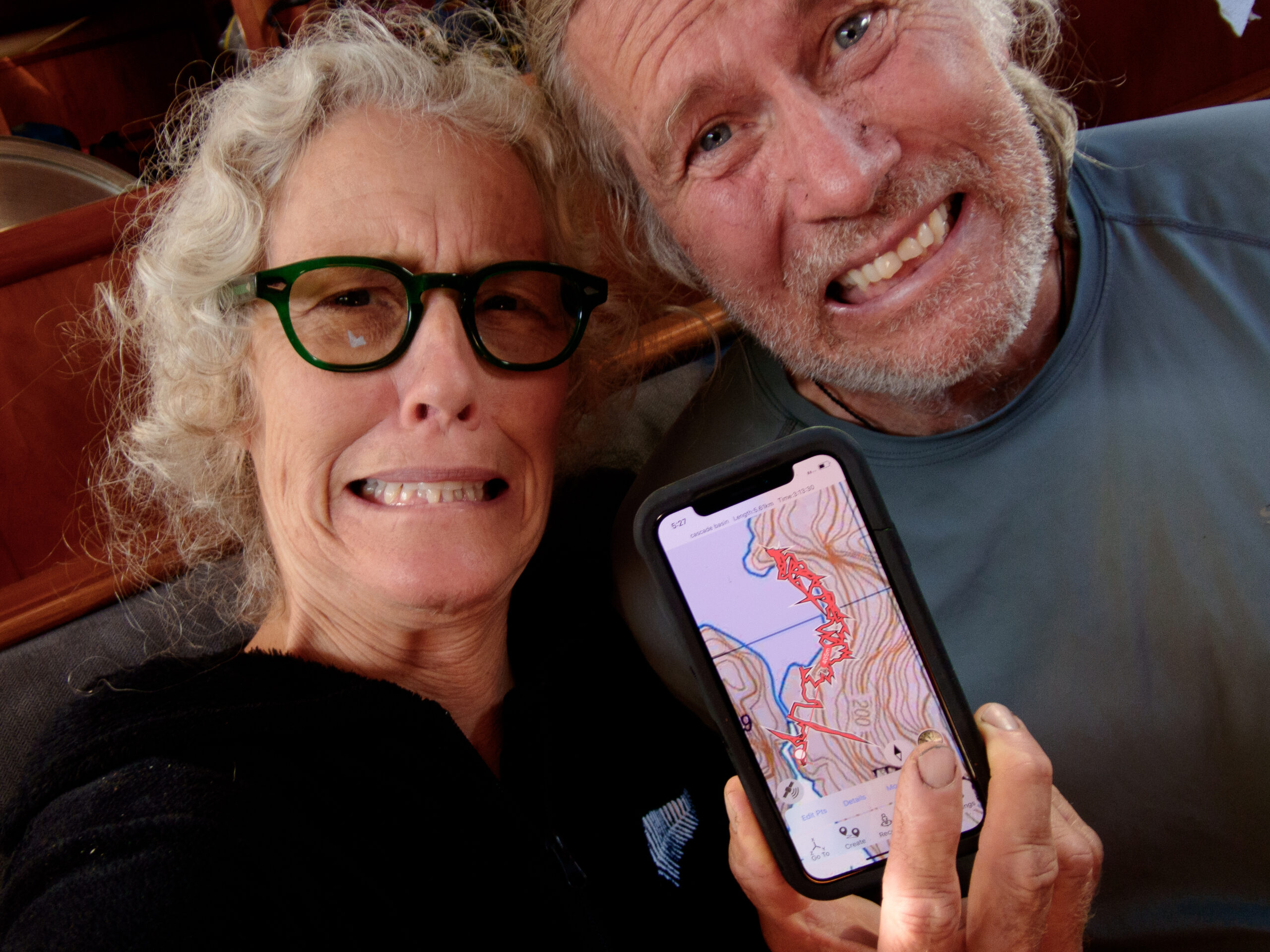

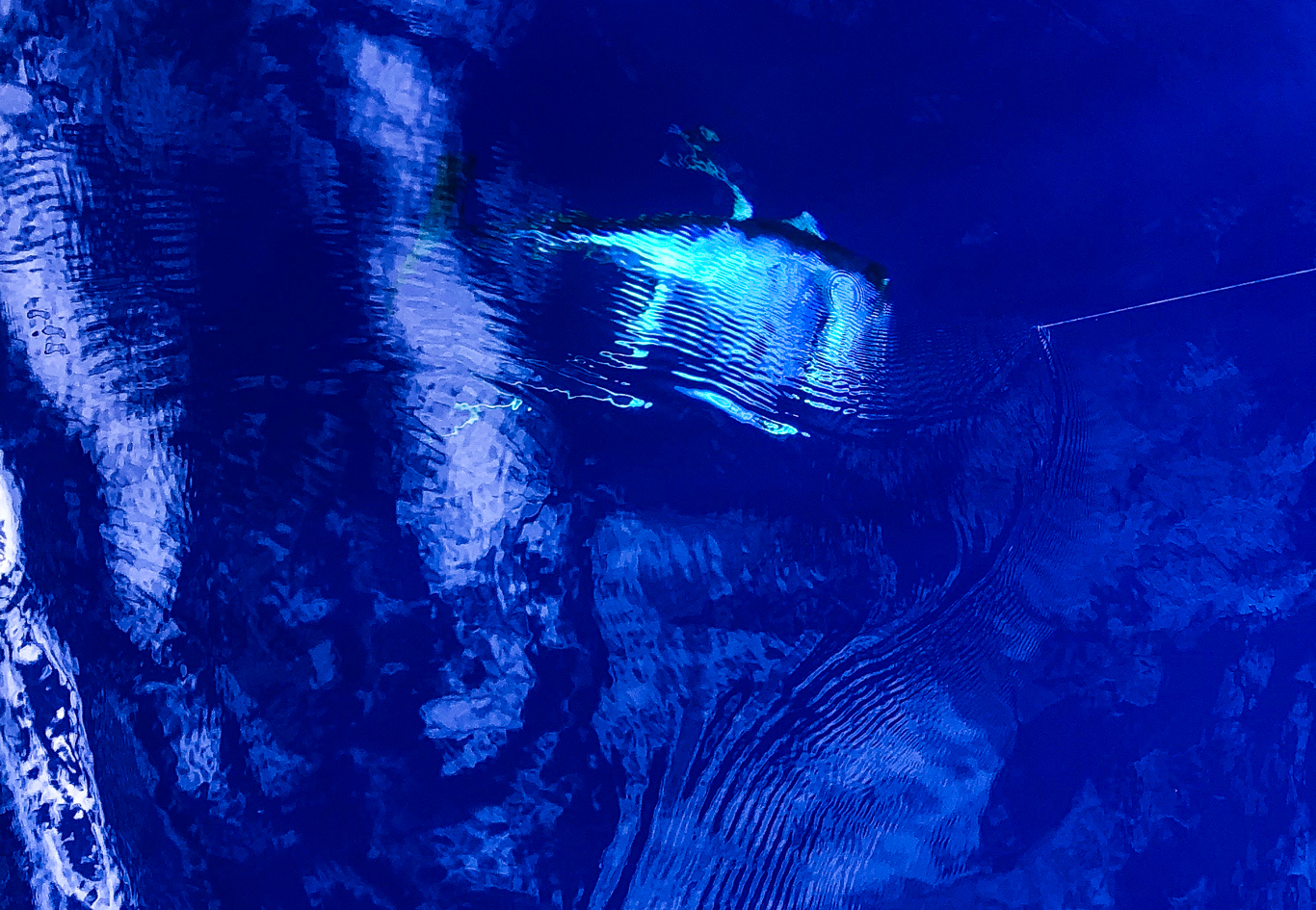

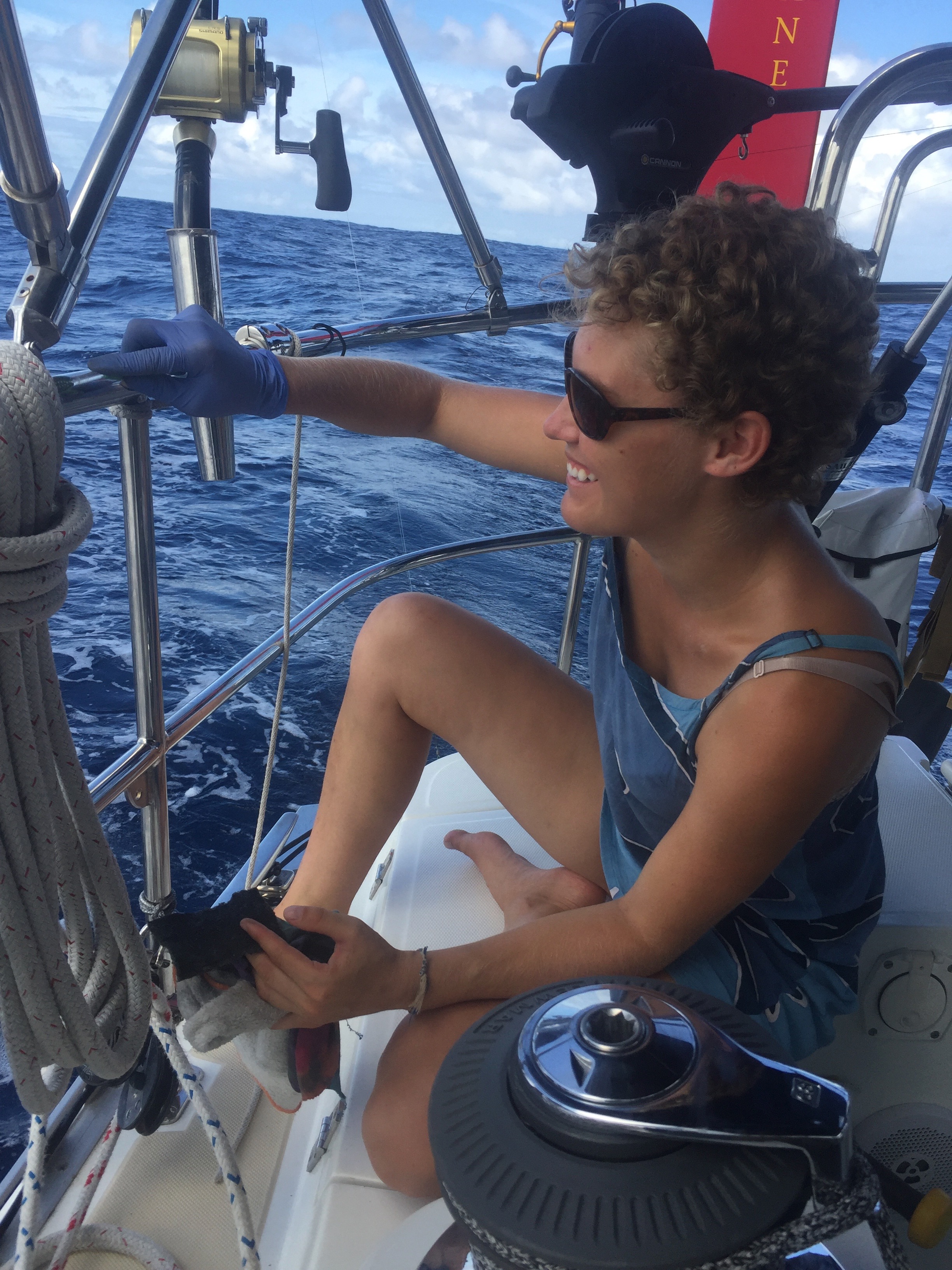

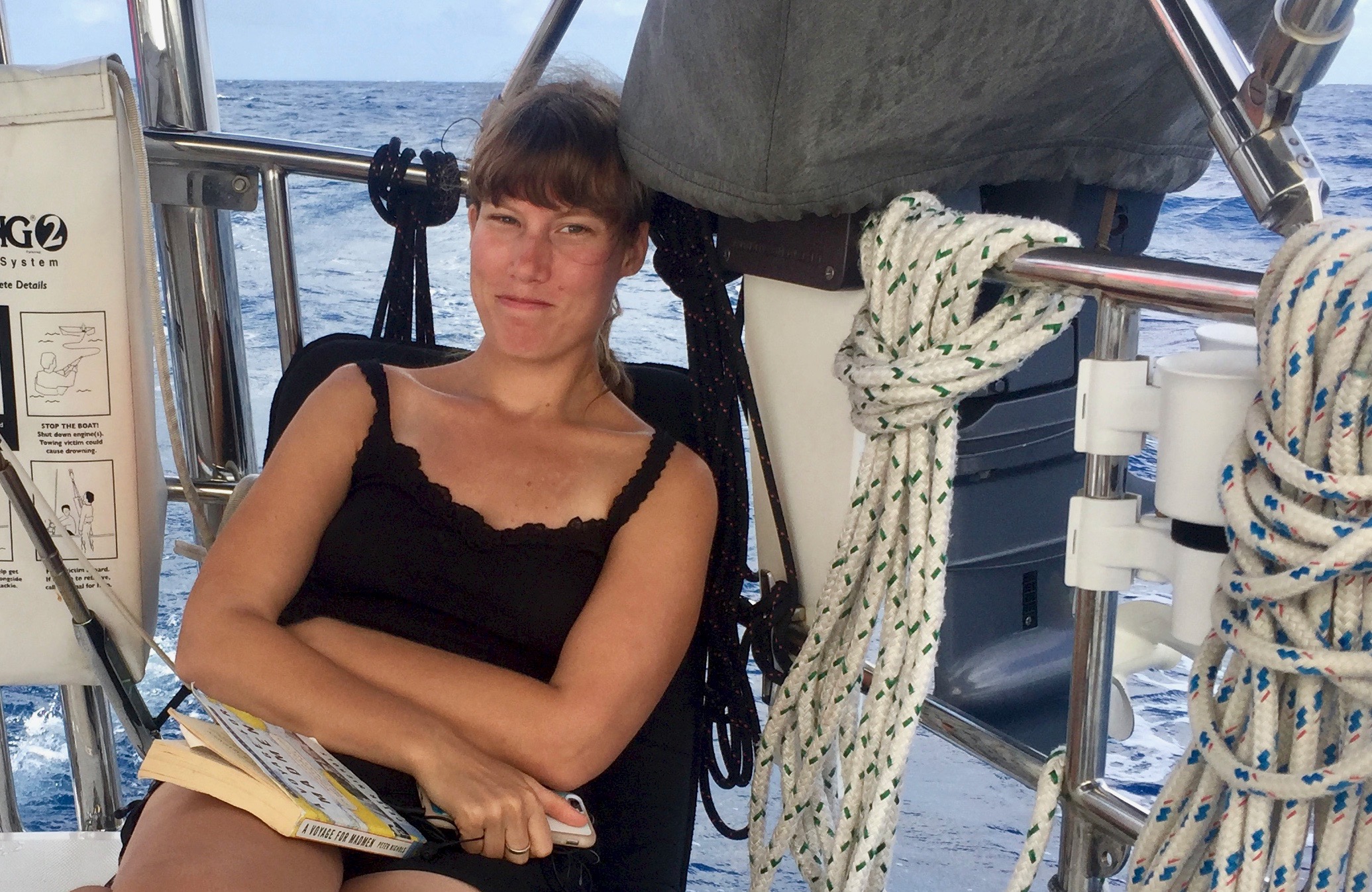

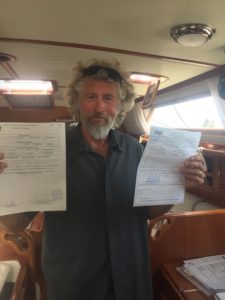

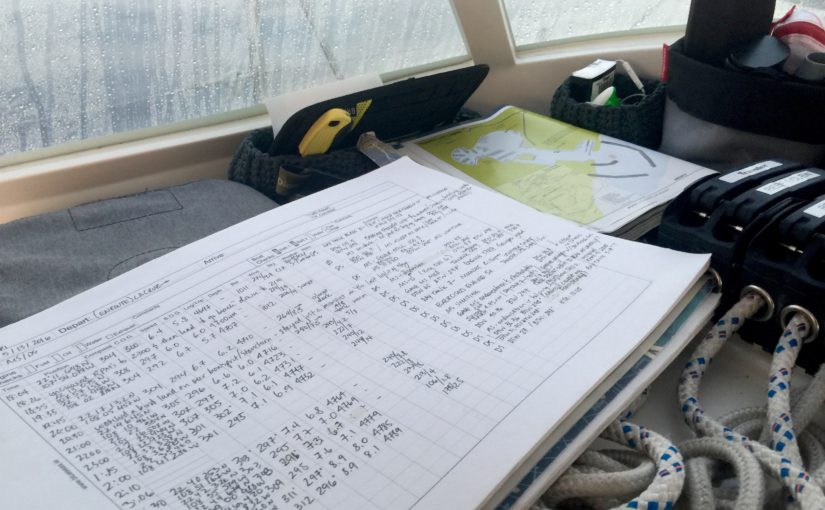

The only photo taken during all the mayhem.

The only photo taken during all the mayhem.