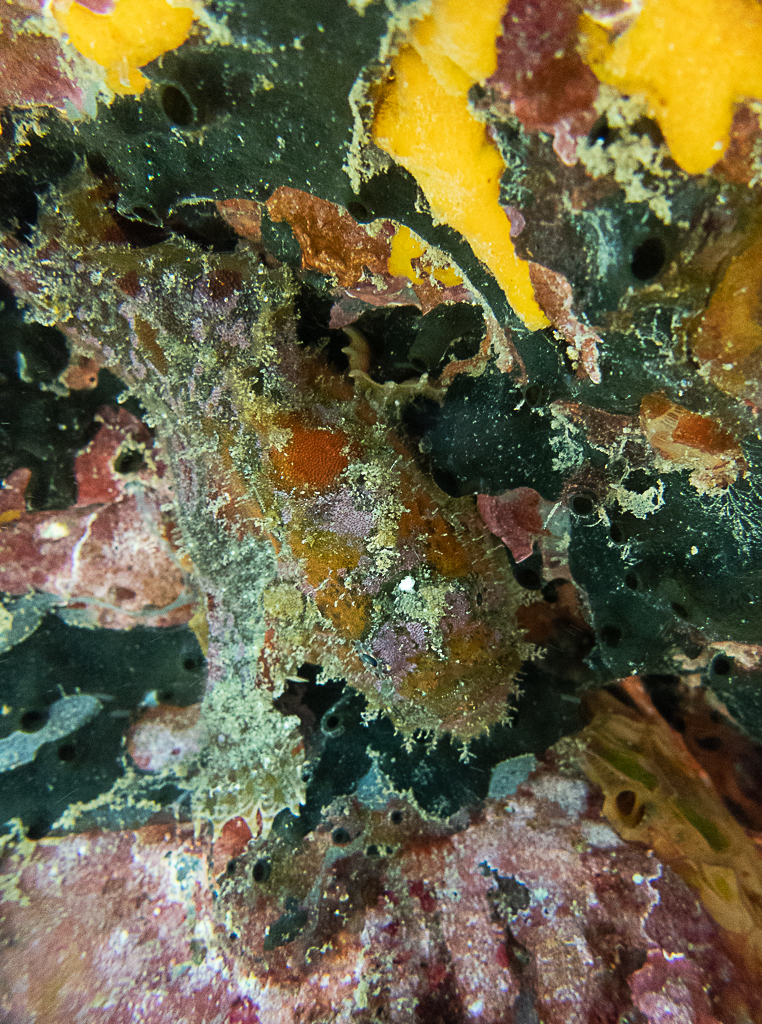

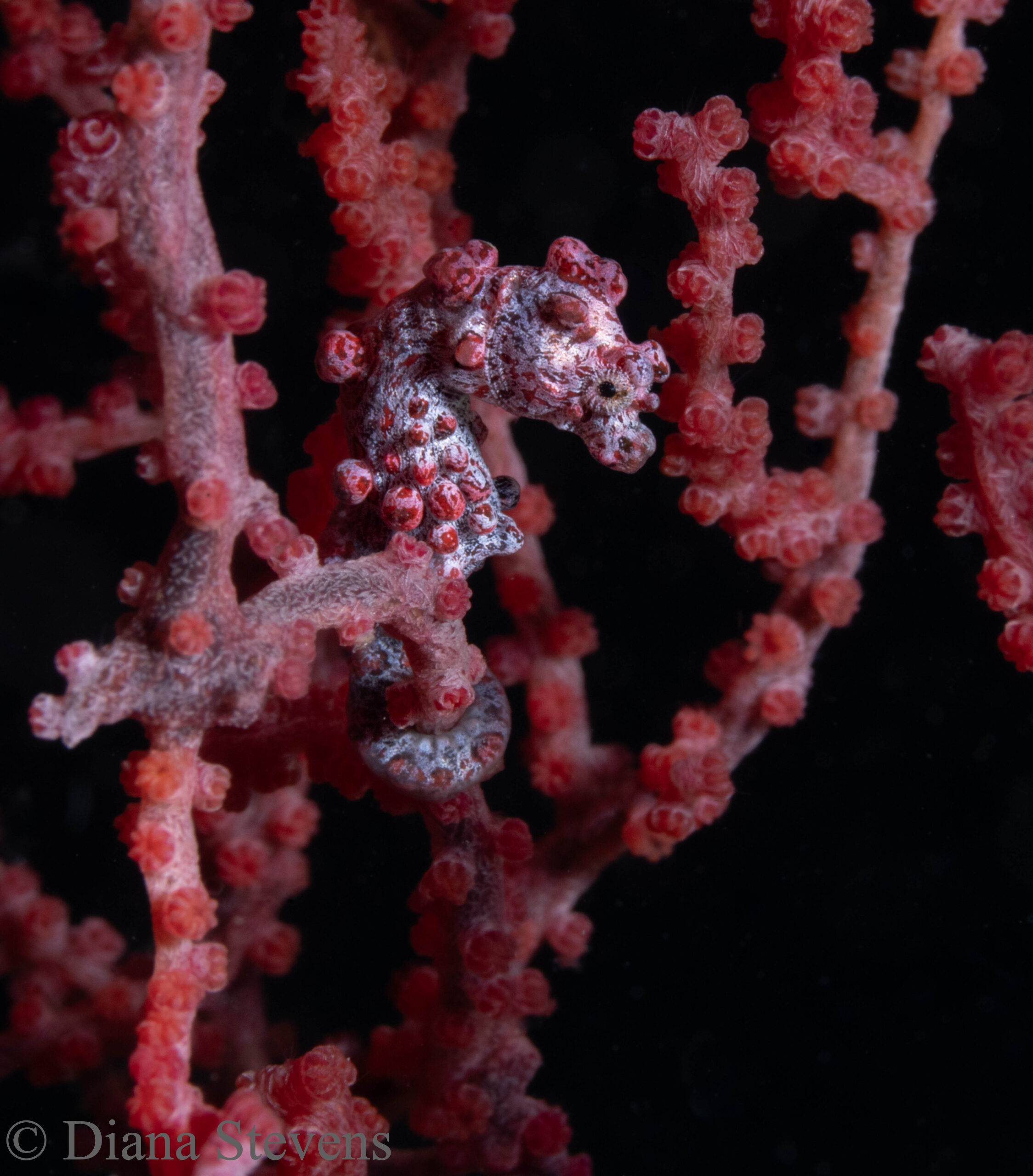

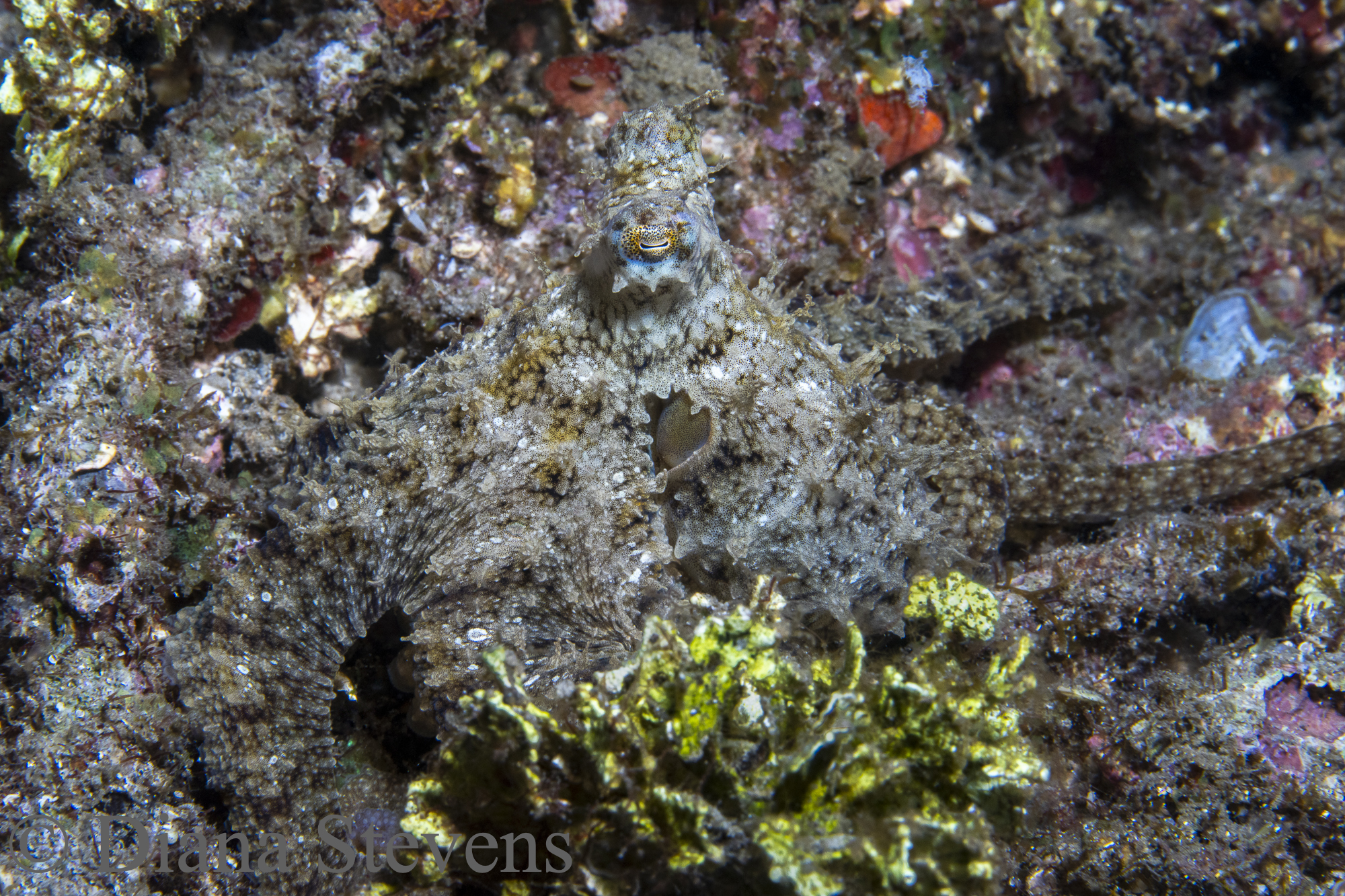

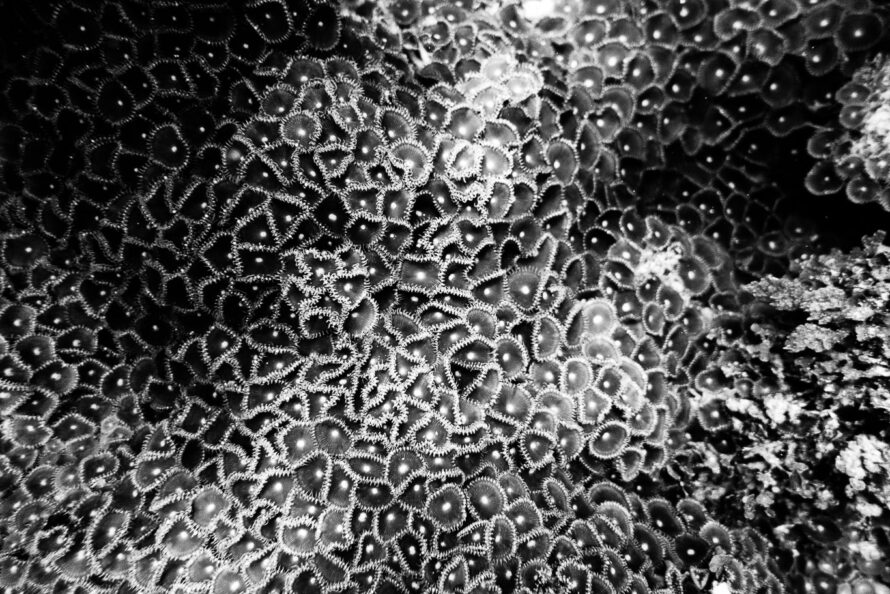

The final Lembeh Strait muck diving album (see the previous two posts for more crazy creatures from these murky waters).

Tag: Firsts

Start MUCKING around!

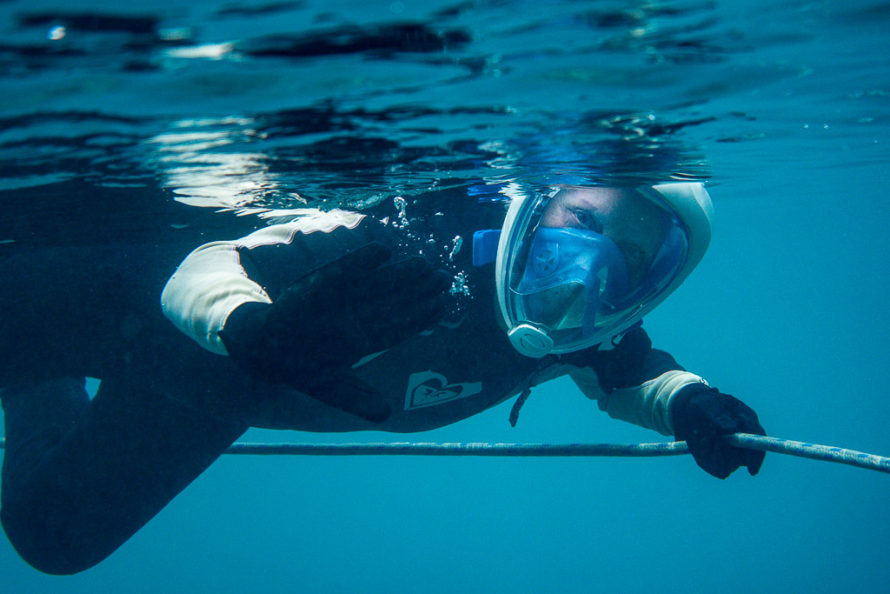

Muck diving is not for everyone. Turns out it’s pretty much what it sounds like, no matter what Diana (and especially her photographs) will try to tell you. Fortunately, at least in Lembeh Strait, Sulawesi, the water’s warm and the visibility is just slightly better than the name conjures. If you go with a dive resort, normal dives times are around sixty minutes. Unfortunately (for me) we didn’t have that restriction, and due to regrettable advances in battery technology and Diana’s ability to forego breathing for extraordinary lengths of time, muck dives with her can run over two hours. I have a bit more blood to keep oxygenated, so I typically get a (usually pleasant) half hour nap in the dinghy at the end of the dive. So not quite two hours in featureless gloom, scouring the rubble and muck for creatures mostly too small for my aging eyes to see even when they are pointed out to me.

Muck diving is not for everyone. Turns out it’s pretty much what it sounds like, no matter what Diana (and especially her photographs) will try to tell you. Fortunately, at least in Lembeh Strait, Sulawesi, the water’s warm and the visibility is just slightly better than the name conjures. If you go with a dive resort, normal dives times are around sixty minutes. Unfortunately (for me) we didn’t have that restriction, and due to regrettable advances in battery technology and Diana’s ability to forego breathing for extraordinary lengths of time, muck dives with her can run over two hours. I have a bit more blood to keep oxygenated, so I typically get a (usually pleasant) half hour nap in the dinghy at the end of the dive. So not quite two hours in featureless gloom, scouring the rubble and muck for creatures mostly too small for my aging eyes to see even when they are pointed out to me.

And yet, I would spend a week in the muck anytime, for the chance to see, in person, two Painted Frog Fish holding hands twenty meters deep in the Celebes Sea. I’m so very happy to live in a universe where that is a thing.

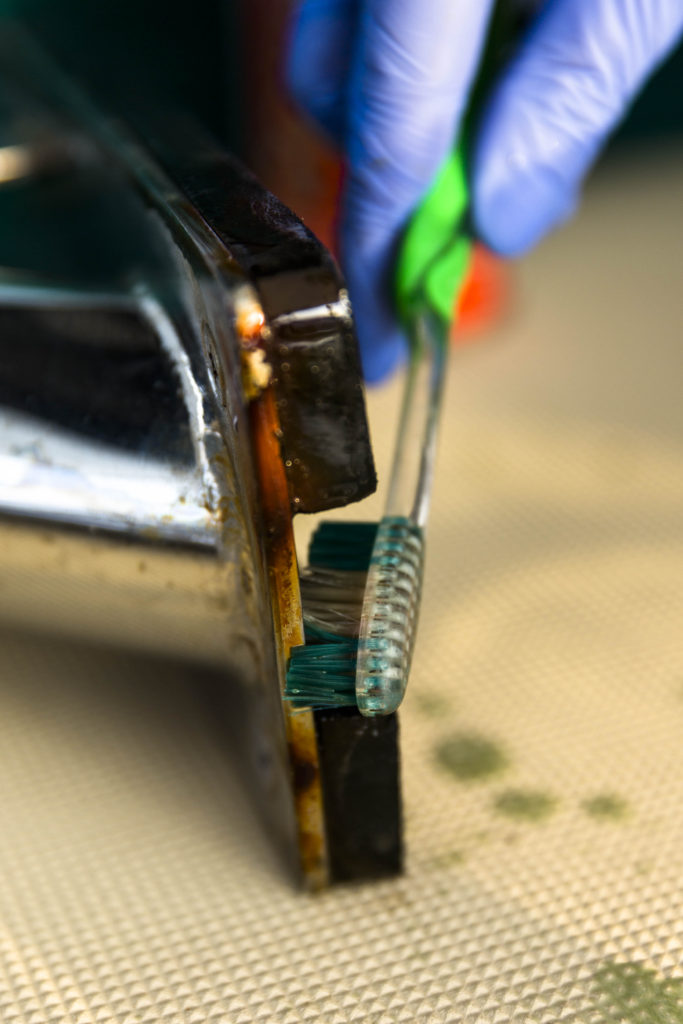

In Lembeh, Diana arranged for a guide which was crucial. Lembeh Resort (phenomenal outfit in every way) set us up with Sandro, a star on their crew, originally from central Sulawesi. He was absolutely delightful to hang out with for six days of diving; easy-going but also a very motivated, perfectly happy to squeeze into Namo – with tanks and gear for three divers – and wallow across the strait at dinghy speed while the professional dive boat he would normally have been on whizzes by. He did occasionally wonder aloud about what might happen if we came up and Namo wasn’t there (with no one to tend to her), but otherwise he was game for diving without a proper boat and happy to stay under for two hours if Diana’s batteries lasted that long. He’s been guiding in Lembeh for years, having worked his way up from being the personal gardener for the dive shop owner, and he’s obviously still fascinated with muck diving. He carried an erasable slate and enthusiastically wrote down names for what he was pointing out to us (often with the proper Latin name). He has a particular interest in photography and works with Lembeh Critter’s camera operation (training other guides and shooting in his spare time) so besides spotting unimaginable, tiny camouflaged creatures buried in the muck, he also was able to help Diana learn how to use the snoot on her strobe light, which gives some of these photographs their dramatic look.

It’s basically impossible to adequately describe how difficult underwater photography is. Start with the idea that literally everything is approximately seventy-nine times harder to do underwater (except maybe peeing in your wetsuit). Buoyancy is super tricky because if you stir up the muck you can’t take photos anymore, and there are seriously dangerous creatures buried invisibly in the sand where you would like to brace your knee. Looking through the viewfinder with goggles is significantly tougher than it might sound (and it should sound impossible). Sony’s “smart” autofocus system hasn’t been down there before either and typically just throws its hands up in the (water?) unless it’s really lucky to recognize an eye. Many of the creatures who’ve developed their camouflage over literally billions of years of evolution are also smaller than a dime, so depth of field is harrowingly scant (breathe and you’ll miss the shot). You’re wearing gloves (for safety), so adjusting things like your f-stop, shutter speed, strobe power or ISO is extra fun. And, of course, though some of these critters do sit still, there’s the usual unpredictability that comes with photographing wild things. I could go on. Basically it’s like the mosaic work Diana does, in that it requires an intensity of focus and bull-doggedness that lies far outside of any normally agreed upon bounds of sanity.

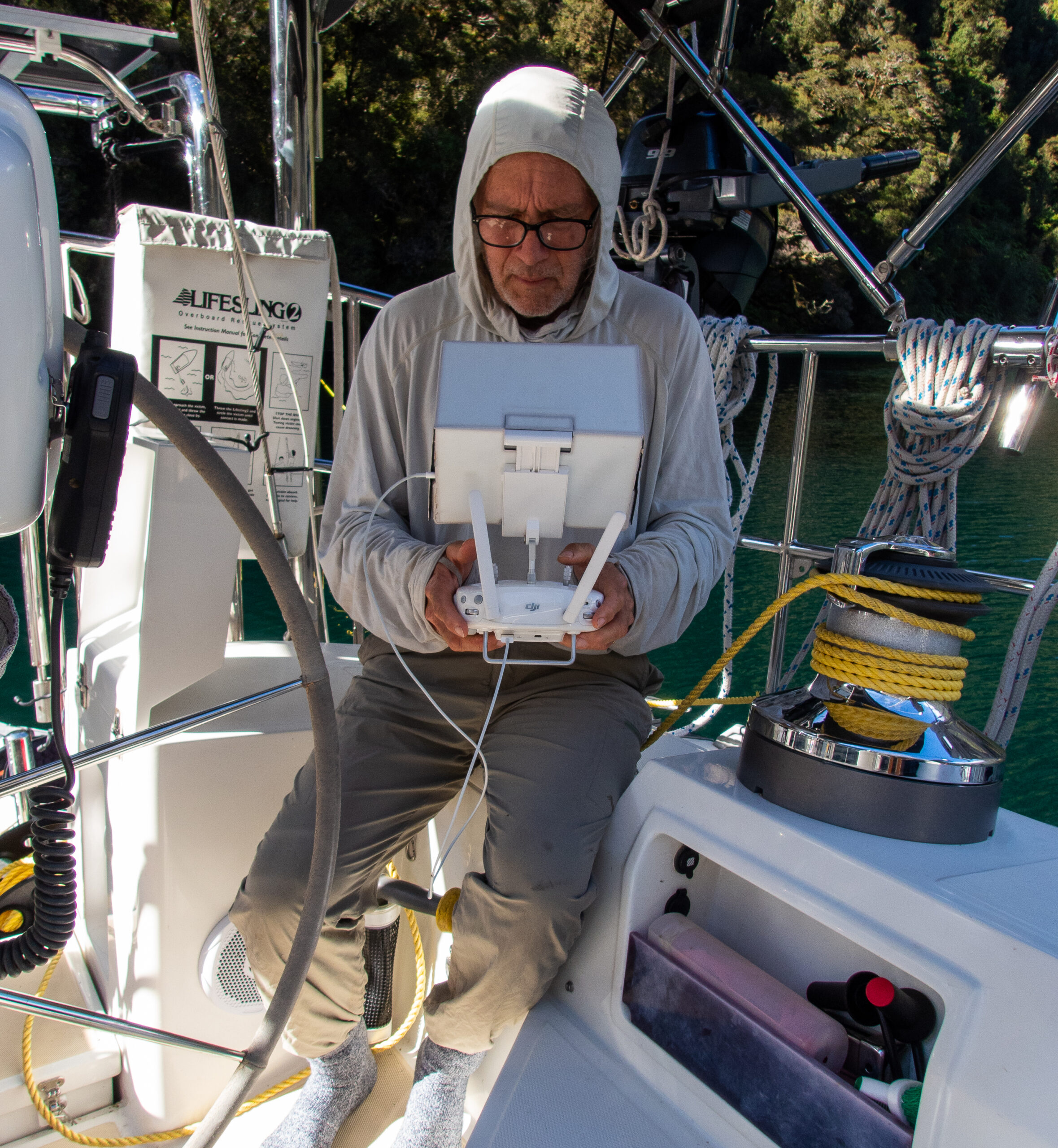

Enjoy the photos (comments are welcome), but also watch the behind the scene’s video I made of Diana and Sandro doing their thing, so you don’t get the wrong idea. ~MS

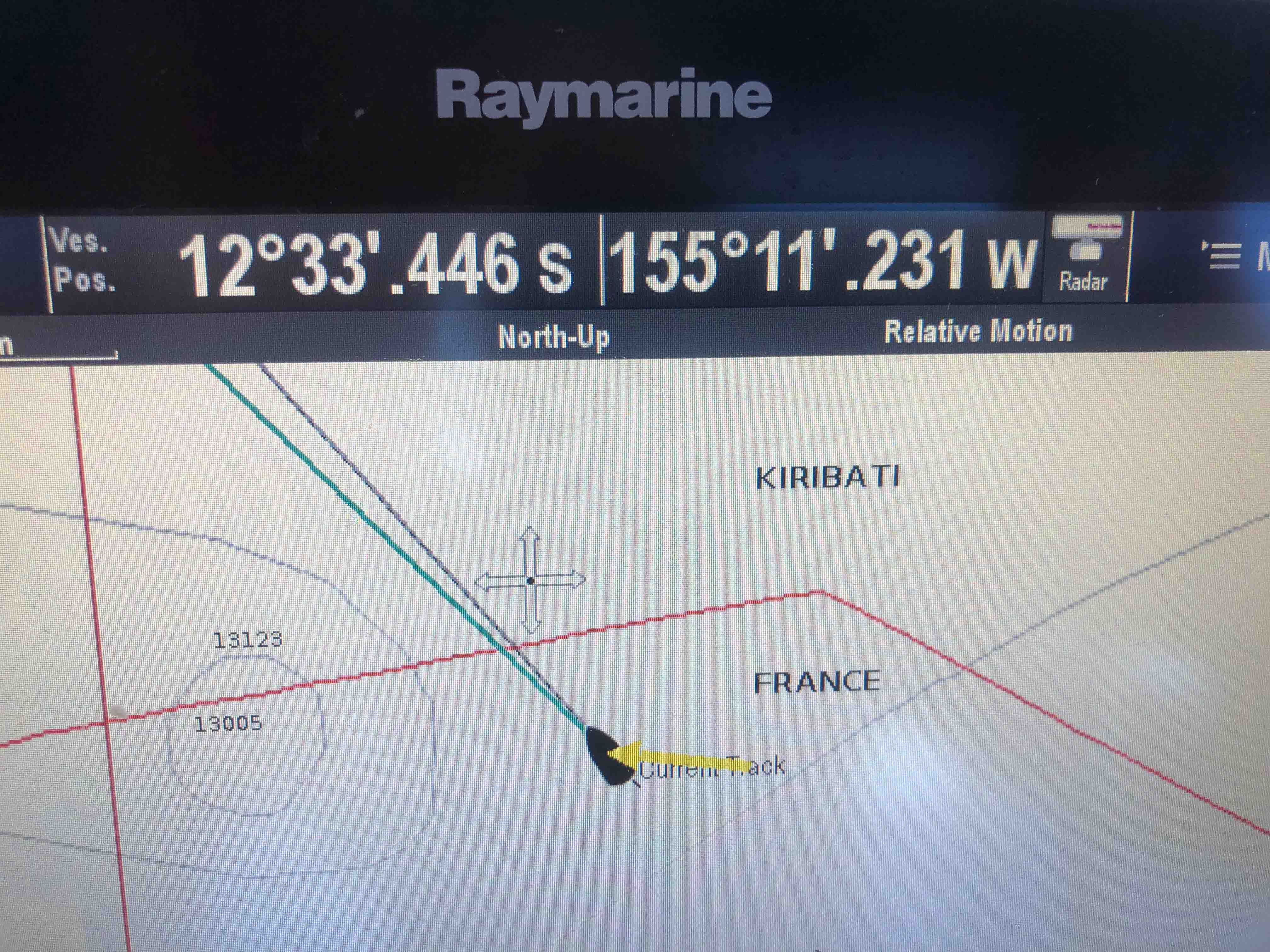

Australia and Tasmania

Allora’s heading off on passage across the Torres Strait and the Arafura Sea from Australia’s northernmost islands to Tual, Indonesia. It’s just us two for this 4-5 day passage and conditions look good; it should be a brisk, downwind sail and we hope/plan to steer well clear of all the reputed fishing fleets! If you’re interested to track us on this passage, our Predict Wind Tracker link is under ‘Where In The World Is Allora.’ Should you need to reach us, head over to the ‘Contact Us’ page. And to AU and her fine people/landscape/creatures, you’ve been a whole lot of wonderful! It’s going to be a tough sail away …

Posts from these past 9 months forthcoming!

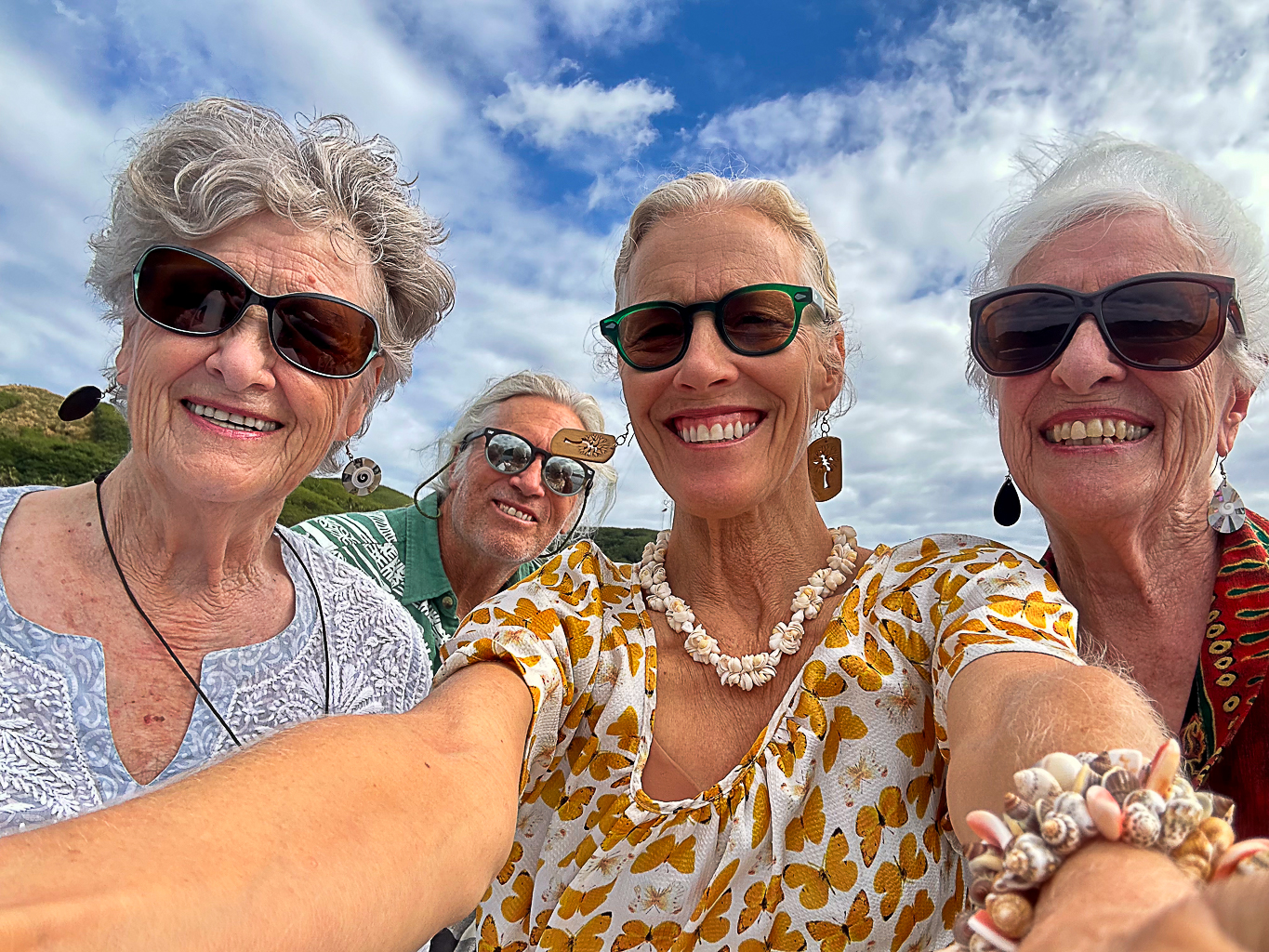

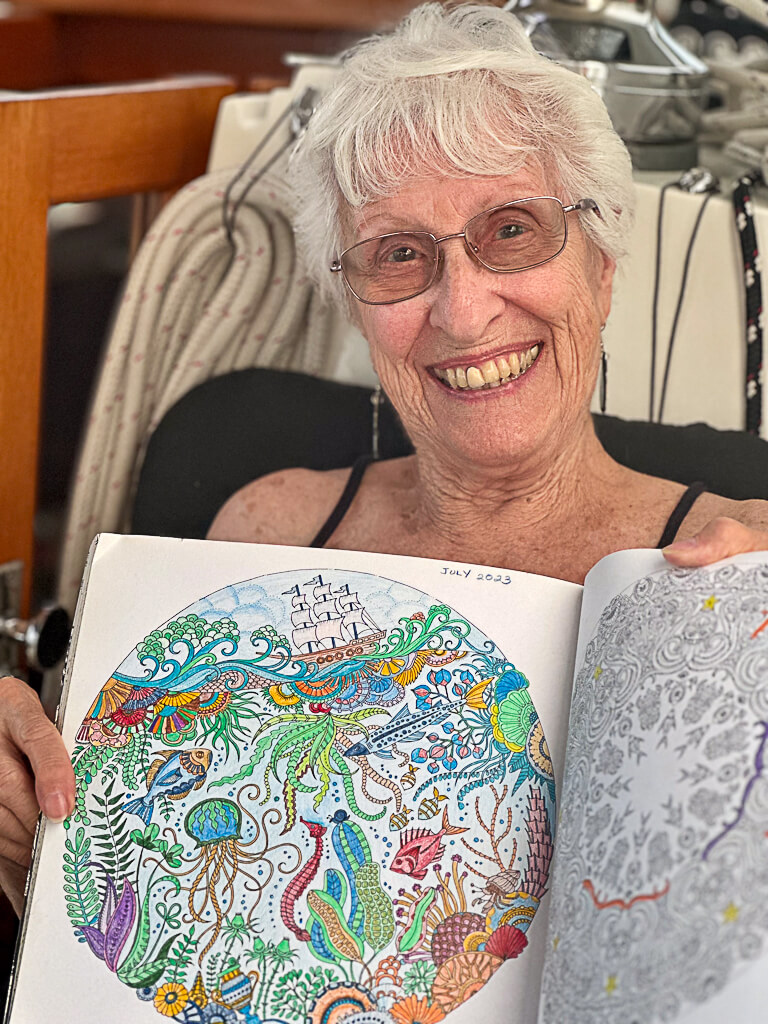

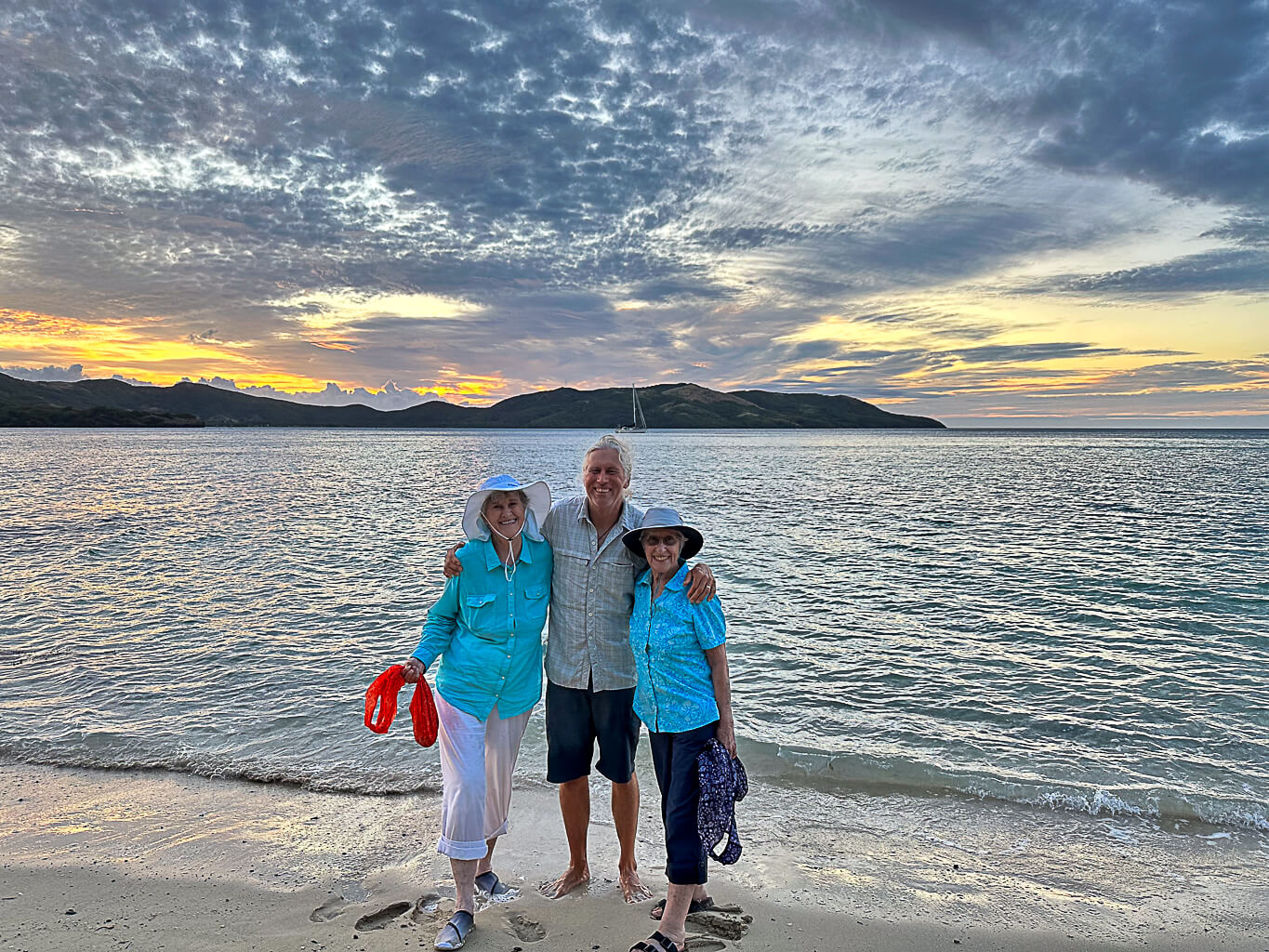

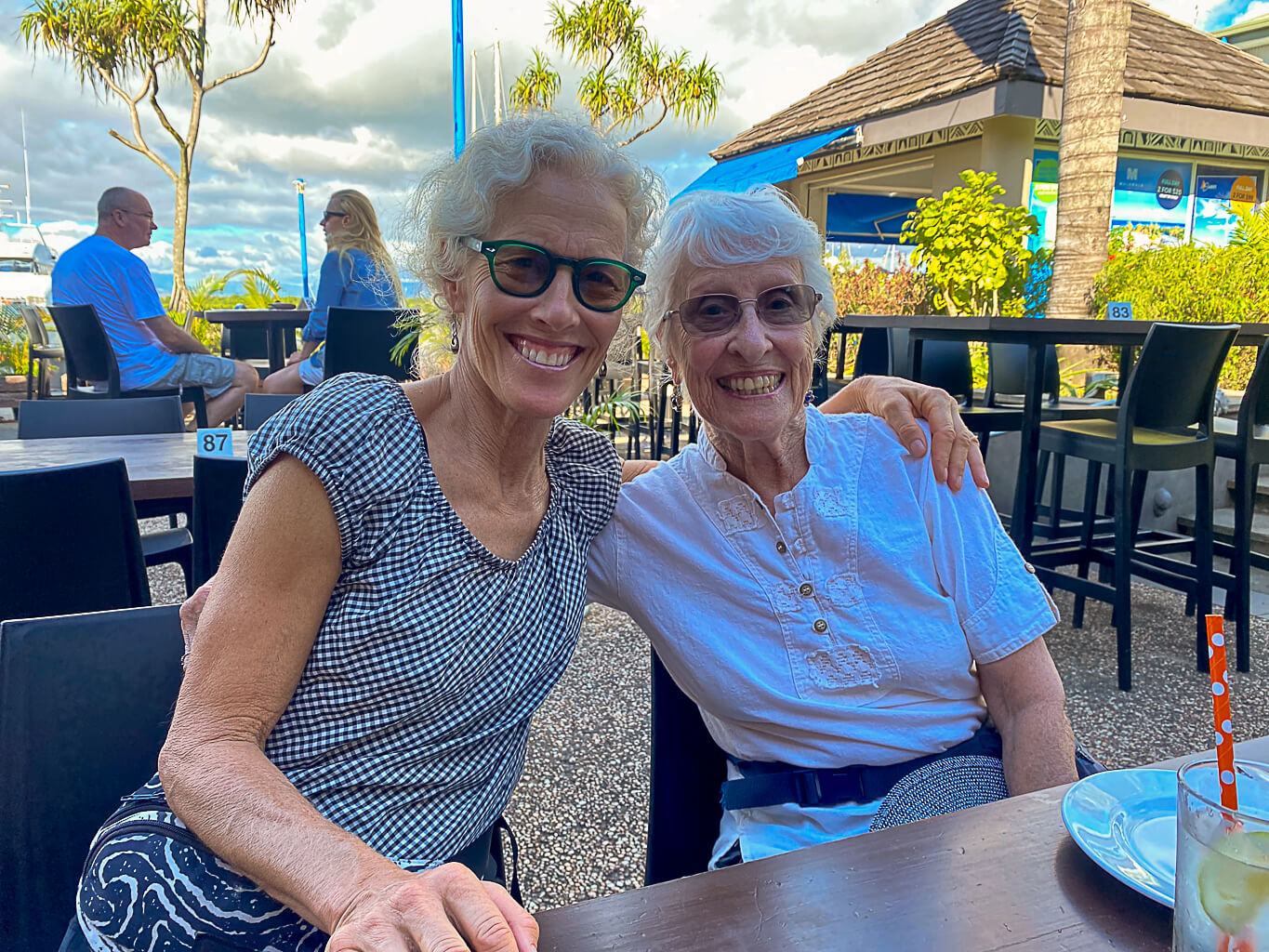

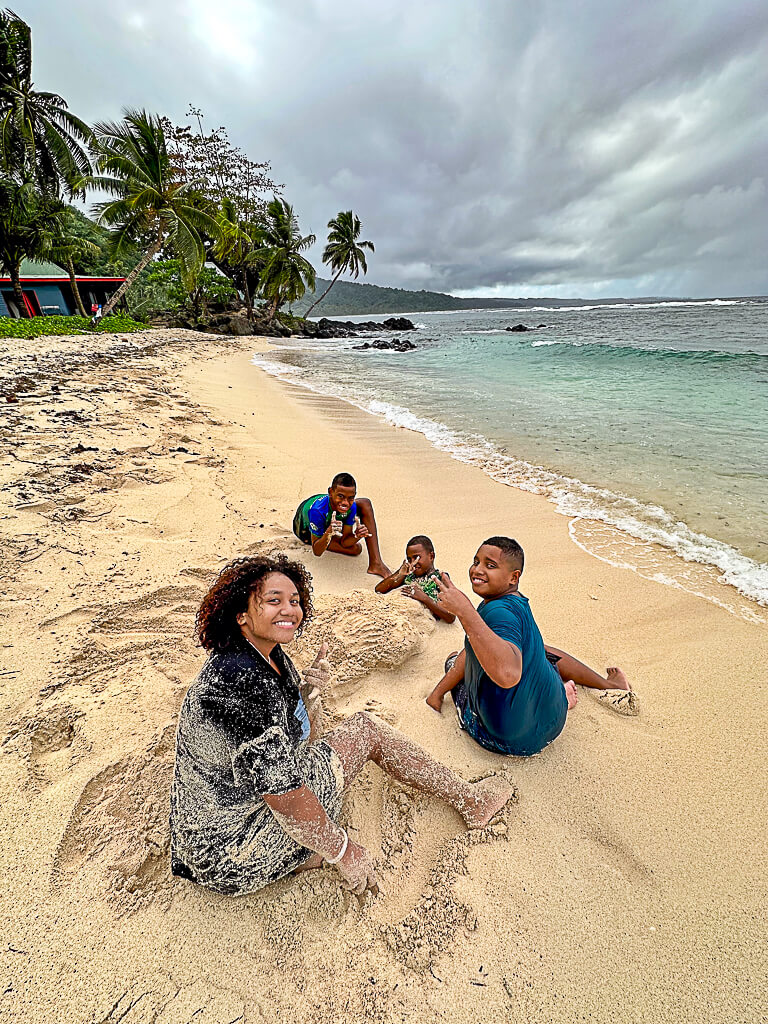

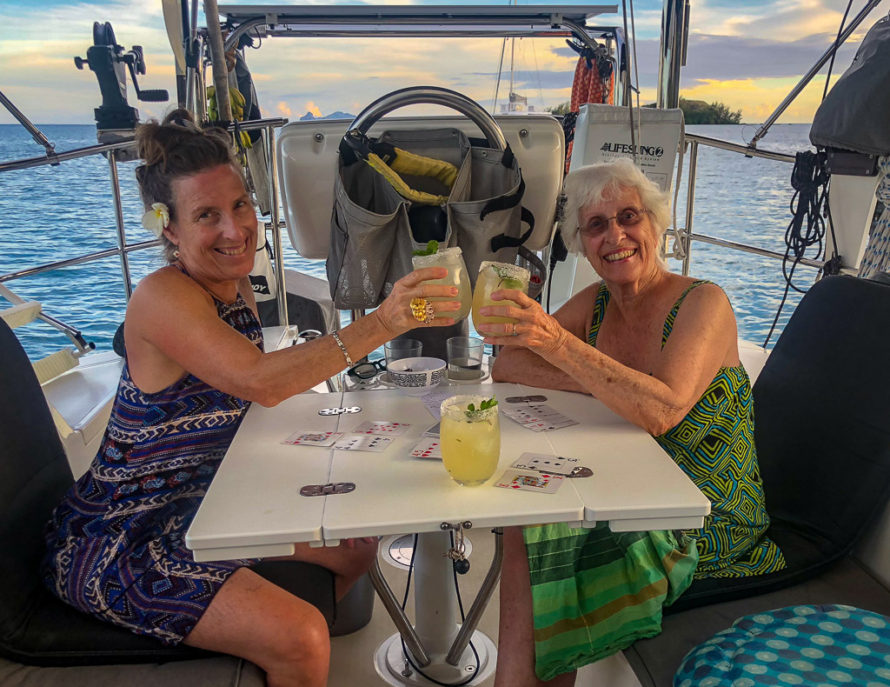

Mamas in the Mamanucas (and Yasawas), western Fiji

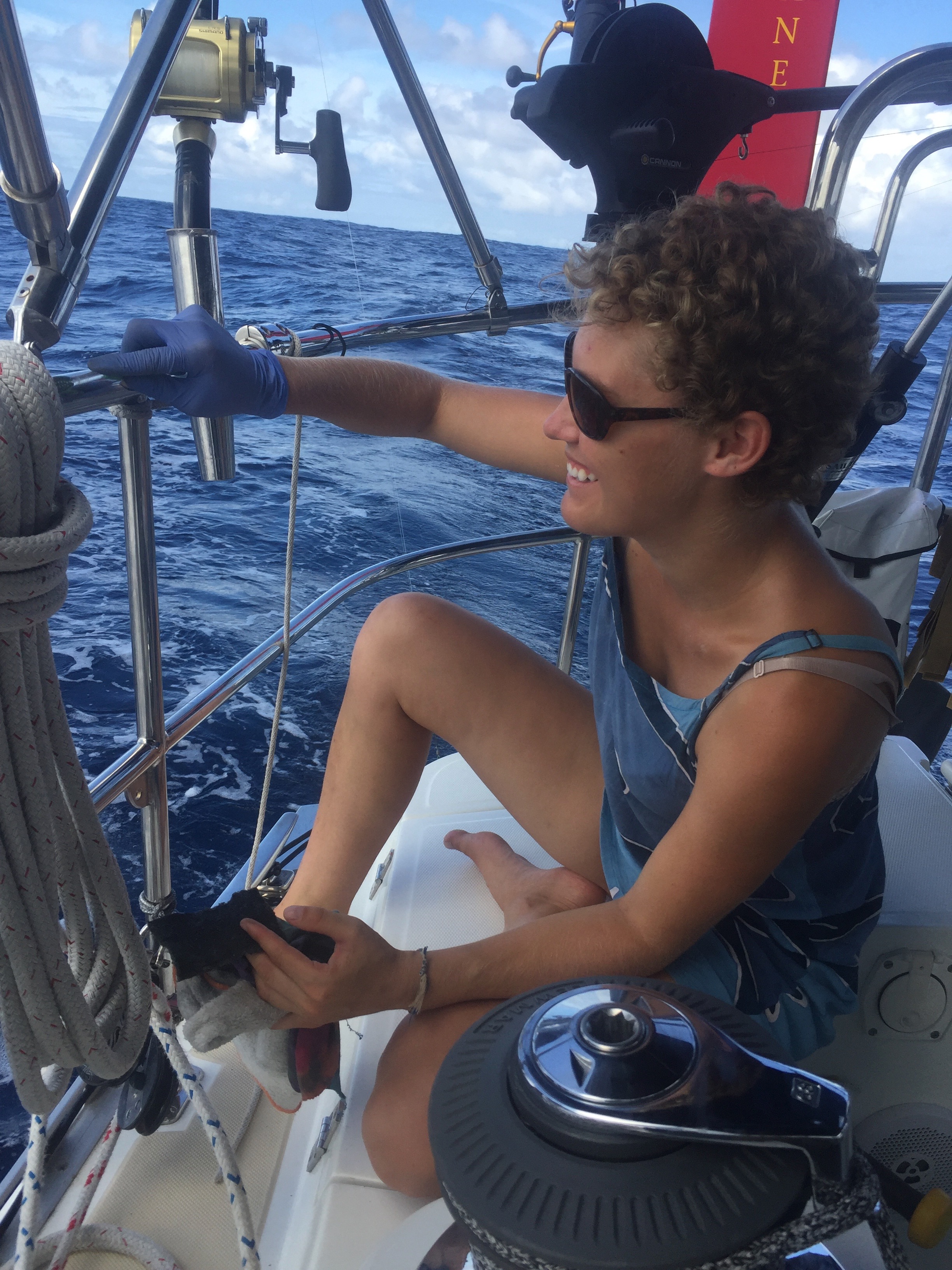

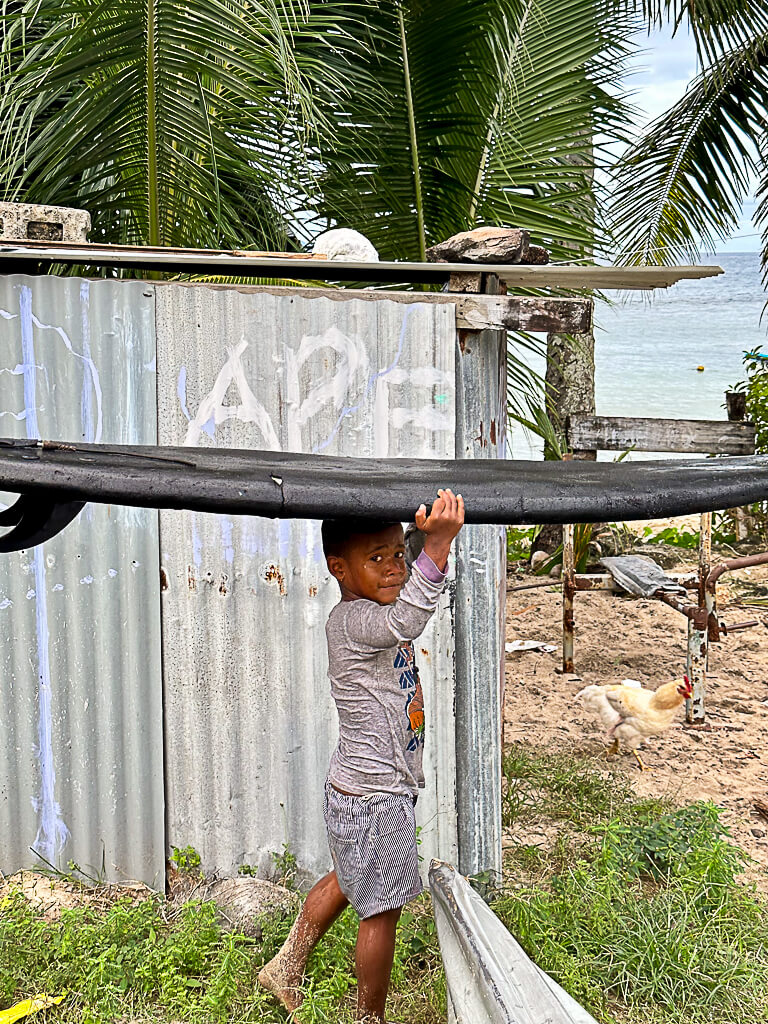

It’s winter in Fiji, which can be easy to forget, usually. Last year we spent a sweltering July in Vuda marina waiting for our transmission, and absolutely no one was talking about cold. This “winter” has felt different (El Niño has officially replaced La Niña). In Viani bay the local dive master talked about rainy weather hanging on longer than usual, hills that were still very very green. “The Moms” arrived for the Fijian version of what overly excited weather people in Montana used to call a Polar Vortex. Fijians donned hoodies and parkas as temps plummeted into the mid-sixties (the lowest temperature ever recorded in Fiji was 12.3 C or 54 F). Meanwhile, “the Moms” counted their lucky stars and gave thanks for overcast days. I put on a T-shirt. Our biggest challenge was finding anchorages that were reasonably calm. Diana tied up the lee cloth for Camille and gave Elizabeth extra cushions to wedge herself in at night. I think I remember Diana suggesting that she handed out more sea sickness medication on this visit than she did on the entire Pacific Crossing. On the bright side, Camille says she has never slept so well (we discussed the feasibility of installing hydraulics in the foundation of her Northern California cottage to replicate these soporific Fijian seas). I think Diana and I had both imagined leisurely lagoon sailing with the Moms, based on our quick survey of the western islands last year. For sure, neither of us imagined gusts to gale force (36 knots), and sailing at 8 knots with a handkerchief of jib rolled out. But by now the Mom’s are seasoned sailors, and weathered it all like old salts, quite happily nestled in their accustomed spots. ~MS

Though the Yasawa’s and Mamanucas (pronounced mamanutha) are more accessible than some areas of Fiji, the culture here seems pretty resilient in coping with the pressures of tourism. All over Fiji people seem to smile a lot — relaxed, unhurried and generally optimistic. I think the Moms particularly enjoyed our cultural interactions. Our first sevusevu ceremony was at Nalauwaki Village in the northern bay of Waya island. The idea of sevusevu is that you must go to the chief of the village to make an offering of kava before you do anything else (swim, hike, fish etc…). Typically you find someone as you land the dinghy on the beach who can take you to the right place (take me to your leader!). The ceremony is usually fascilitated by the chiefs spokesperson, the Turanga Ni Koro. You sit on the floor in the chief’s house or the community hall and pass your kava roots (usually wrapped up in newspaper which is also valued for rolling very long thin cigarettes called Suki) to the spokesperson who passes it onto the chief. He recites a speech (in Fijian) welcoming you, often by name, giving permission to walk about the village, snorkel, dive etc. The spokesperson translates that you are now guests and the chief and the village also take responsibility for your welfare. The ceremony is usually followed by a tour of the village and the school. Apparently Nalauwaki has been without a chief for a while, so this first sevusevu was a very low key version with an elder, but still had the intended effect of making us feel connected to the village rather than outsiders. All over Fiji the custom of not wearing hats, sunglasses, or carrying backpacks on your shoulders is a way that tourists can show their respect for the village. In the Lau group of eastern islands, I also started wearing a sulu (a wrap around skirt for men and women) for the ceremony as another sign of respect. It feels surprisingly good to be welcomed in this formal way and the ceremony really does create a feeling of attachment and mutual responsibility. ~MS

Since we arrived and offered our sevusevu on a Saturday we knew we would be invited to come to church on Sunday. Since it involves singing, Elizabeth and Camille were all in. We’ve been to church a few times in French Polynesia, the Cook islands and in Fiji. Mostly they’ve been very traditional, patriarchal affairs. Here they are conducted in Fijian, with a brief nod in English to visitors. The singing is the standout part of these Sunday gatherings with stunning acapela harmonies that were very moving. The tone of the sermon at the beginning also seemed softer than we have encountered elsewhere. What really stood out for me, which I’m sure I will never forget was when the pastor asked all the parishioners to offer their own private prayers aloud at the same time. The murmur of all those voices blending together was pure magic. The congregation then endured a very long scolding which seems de rigeuer for these weekly sermons (thrice each Sunday minimum, at 5AM, 10AM and 3PM). The children deserve special mention for managing superhuman patience without the usual oversight of one of the villager elders wielding a long stick which we’ve seen most other places. ~MS

Since we arrived and offered our sevusevu on a Saturday we knew we would be invited to come to church on Sunday. Since it involves singing, Elizabeth and Camille were all in. We’ve been to church a few times in French Polynesia, the Cook islands and in Fiji. Mostly they’ve been very traditional, patriarchal affairs. Here they are conducted in Fijian, with a brief nod in English to visitors. The singing is the standout part of these Sunday gatherings with stunning acapela harmonies that were very moving. The tone of the sermon at the beginning also seemed softer than we have encountered elsewhere. What really stood out for me, which I’m sure I will never forget was when the pastor asked all the parishioners to offer their own private prayers aloud at the same time. The murmur of all those voices blending together was pure magic. The congregation then endured a very long scolding which seems de rigeuer for these weekly sermons (thrice each Sunday minimum, at 5AM, 10AM and 3PM). The children deserve special mention for managing superhuman patience without the usual oversight of one of the villager elders wielding a long stick which we’ve seen most other places. ~MS

There’s not a whole lot of material wealth in most of the Fijian villages we visited, and an obvious shortage of healthcare. People here are pretty self sufficient and work hard to supply their own needs. They mainly sleep on the floor in very simple, but colorful houses. Still, the land and sea also seem generously willing to provide the basics. Papaya (and a lot of other things) do grow on trees. While we anchored off a small uninhabited island wondering if the rain and cold weather might ease, if the northern swell might finally cede the battle to a southeastern blow and give Allora some peace, I noticed a local fishing boat anchored further out where there was no protection. Their single light bounced and rolled all night as they fished, despite the seriously uncomfortable weather for two days. Fishermen in the islands spearfish at night just like the sharks because the fish are hiding out in the rocks and make easier pickings. No bunks or cushions on that boat, no seasickness medicine or Diana cooked meals either. ~MS

The highlight of the Moms’ visit (besides the music), was the slow mornings and conversation. It seems like most days we sat in the cockpit losing track of time until almost noon, typically with a wonderful brunch whipped up by Diana (with assistance from her favorite sous chef). Just being in the same space together with Allora gently (or sometimes not so gently) rocking, turning in the breeze (or gale) was all we needed. We covered most topics ranging from the essential meaning of the universe to childhood memories of mixing the yellow coloring into margarine. Maybe the same thing, actually, as I think about it. ~MS

These Mama visits always leave me filled to the brim with what feels like elemental GOLD, but as we say our goodbyes, the fullness gives way quickly to a longing for more. Though the days are relatively few, they are packed with meaning: laughter, stories, music, belonging, acceptance … how would I resist this grasping? In the days following their departure, I am reminded that all the gifts of being in the graceful company of these two women are still right here with us. Vinaka vakalevu. What treasures our Mamas are! Till the next time, you two … Sota Tale! ~DS

A visit from our Kiwi (resident) kin:

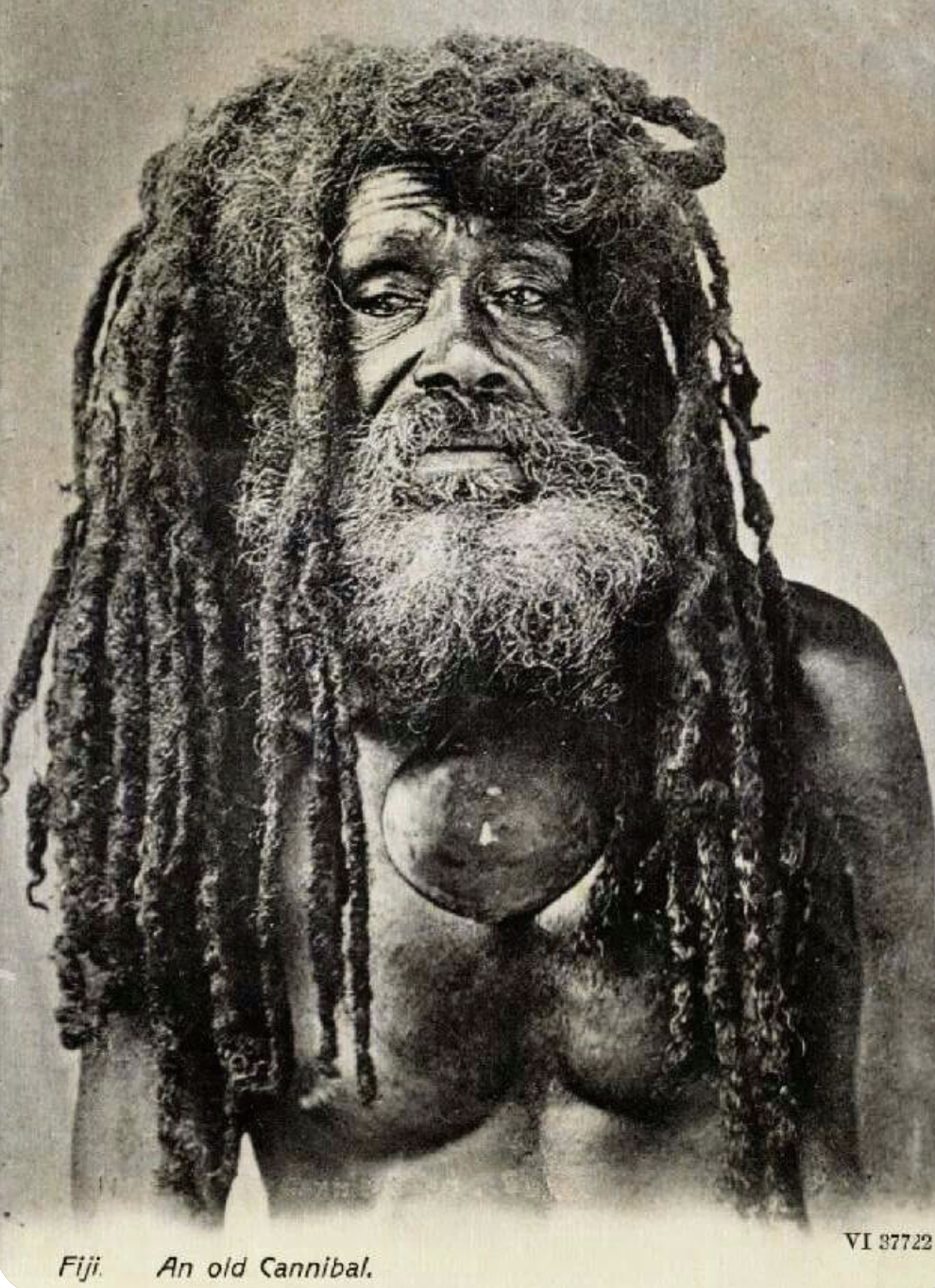

In the bar at Paradise resort, there’s an historically dubious caption pasted on a black and white picture of a dreadlocked Fijian, claiming to be of Udre Udre, famous for eating 872 or 999 people, which raises the question of who’s keeping those records? Seems a bit incredible until google informs you that the average American will consume 7,000 animals in a lifetime (vegetarianism anyone?). ~MS

from a joy perspective than any other village ceremony.

“Fiji night” kava and a guitar missing the D string. Traditional dances offered by the employees (which they must learn as kids) casual enough to feel authentic. We share the end of the table with doctors and nurses from San Diego who come to the island each year to volunteer their services for local women, long days providing surgeries that otherwise require a long trip to the mainland. Paradise is their reward at the end of a non-stop week. ~MS

Liam remarked on the mighty trees that line the long ride down the island of Taveuni, arched over the battered road, lush and green. Glimpses of the blue tropical water in the Somosomo Strait between Vanua Levu and Fiji’s rainiest island. Here’s where the 180th meridian plays funny games with our navigation programs, and astronomically speaking the date should properly change. The dive resort at the end of Taveuni, calls itself Paradise. “Welcome to Paradise” probably gets old for the staff. Or maybe not. Green vines with blue flowers tumble down black volcanic rocks and red dirt off shore. After school, kids leap into the gentle blue surge in the glowing warm sunset. Tucked under the dock a frog fish holds perfectly still, out by the yellow can bouy, blue ribbon eels poke their heads out of the sand, waving back an forth with as must bluster as they can muster. ~MS

A windy Lavena coastal walk, winding up the luxuriant Wainibau valley to the thundering falls. The usual swim against the current in warm fresh water, clinging to the cliff walls between dashes across the torrent. Liam and Diana make it the whole way. A 70 year old Fijian guide urges his charges on, climbs the cliff for a daring dive he must have made since a child. ~MS

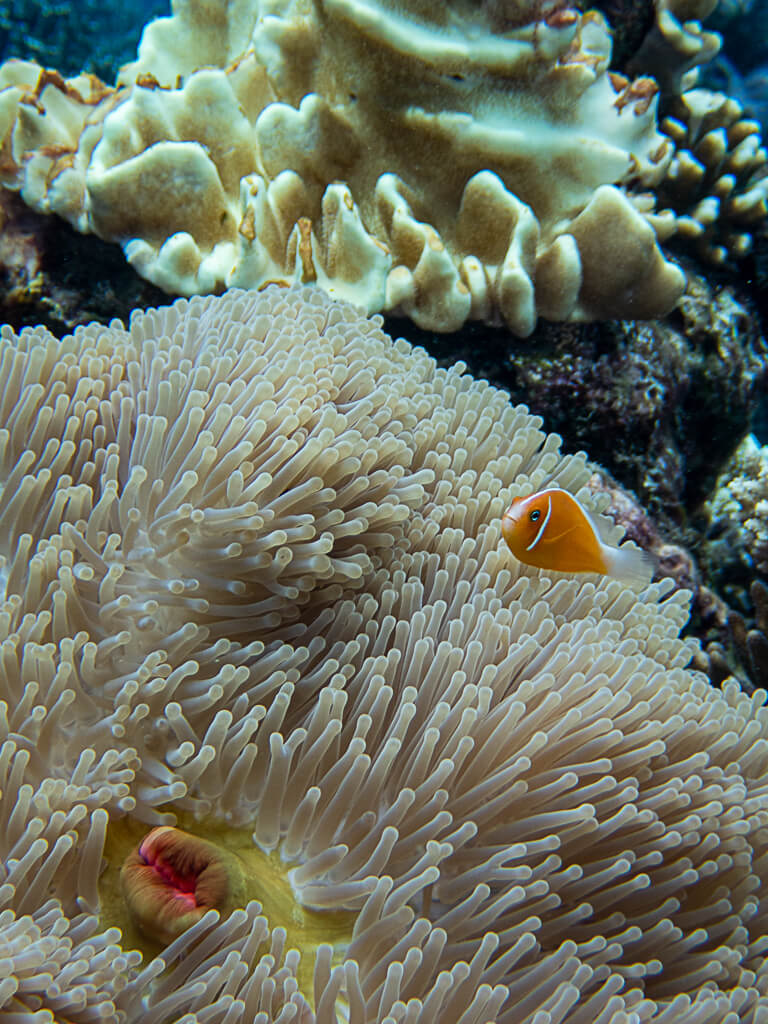

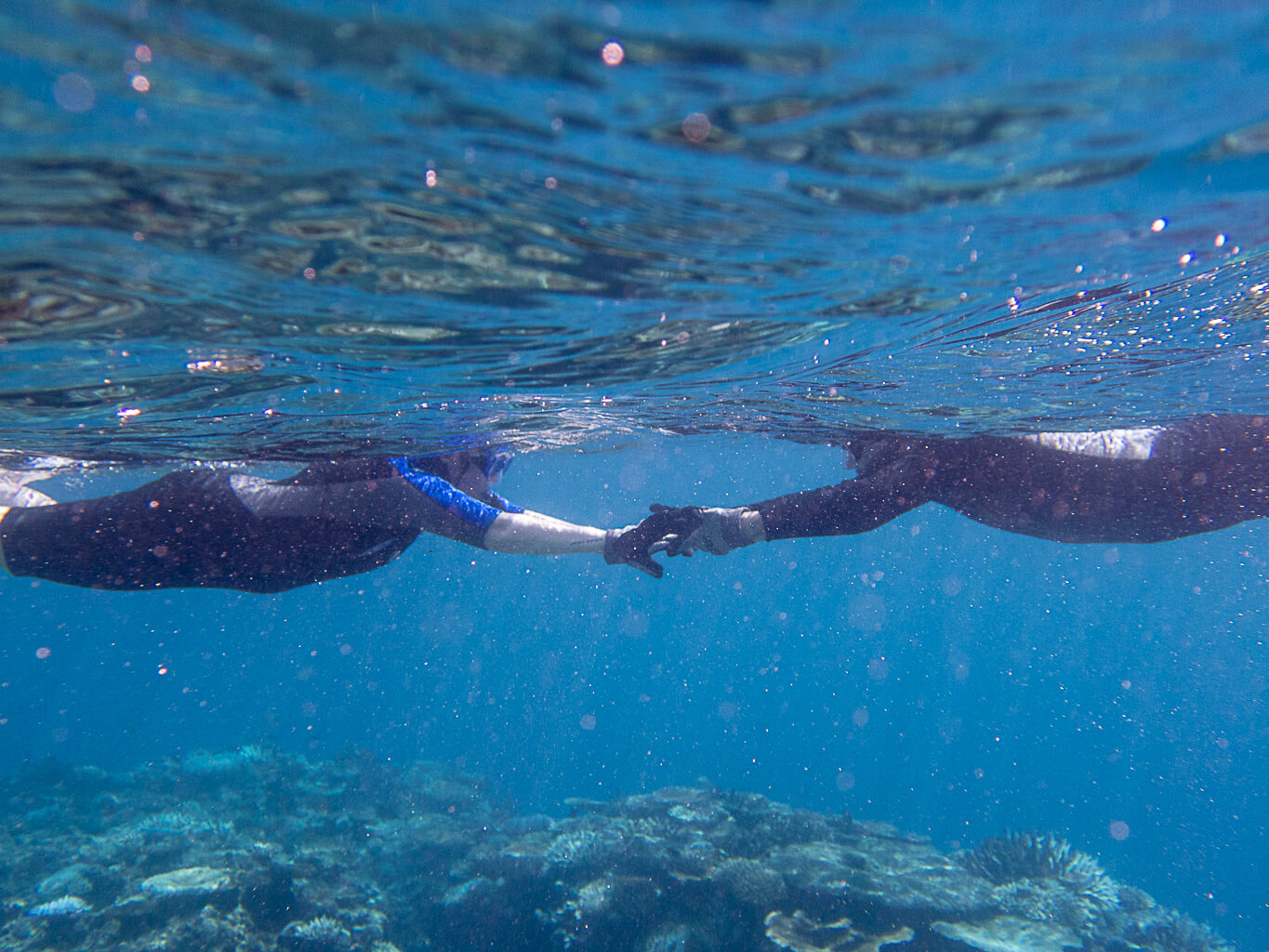

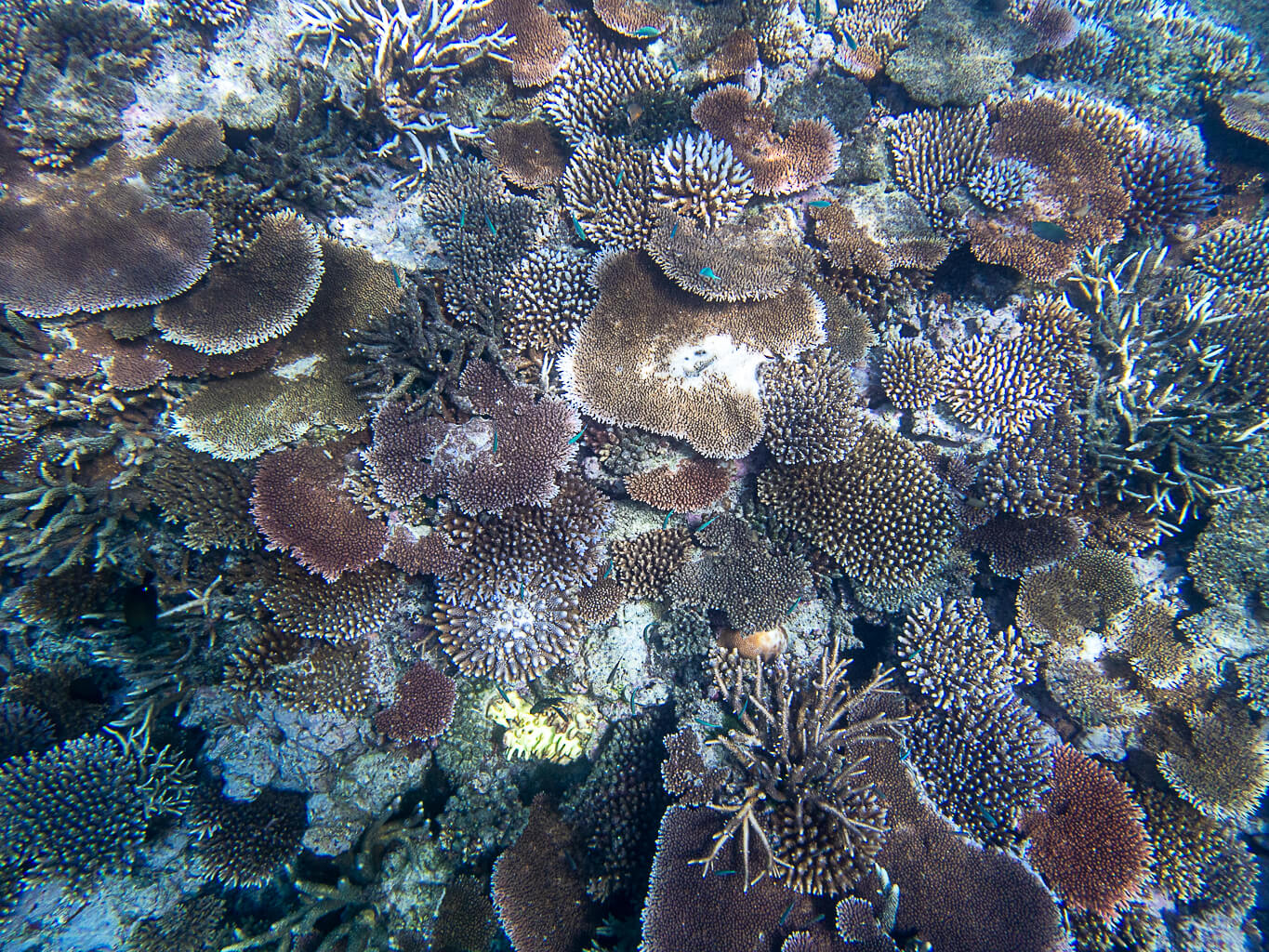

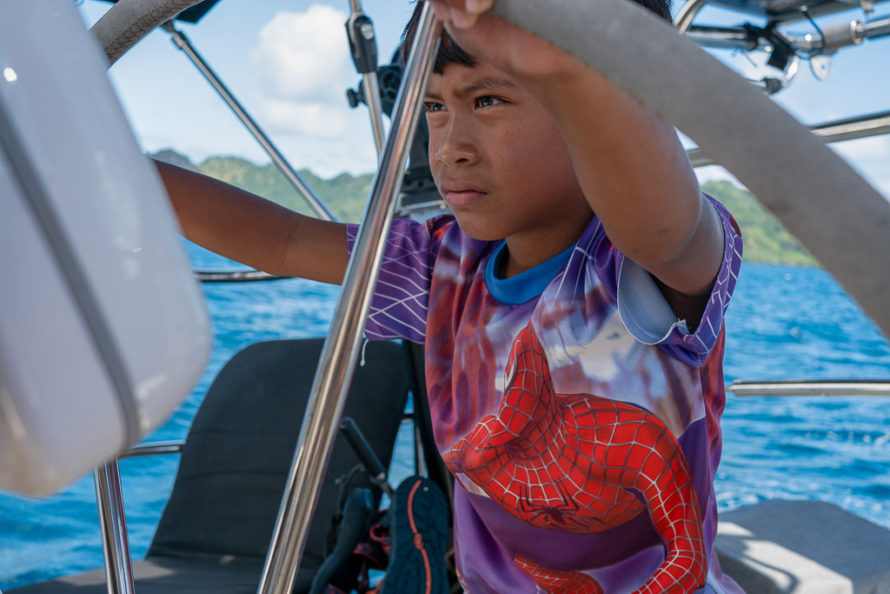

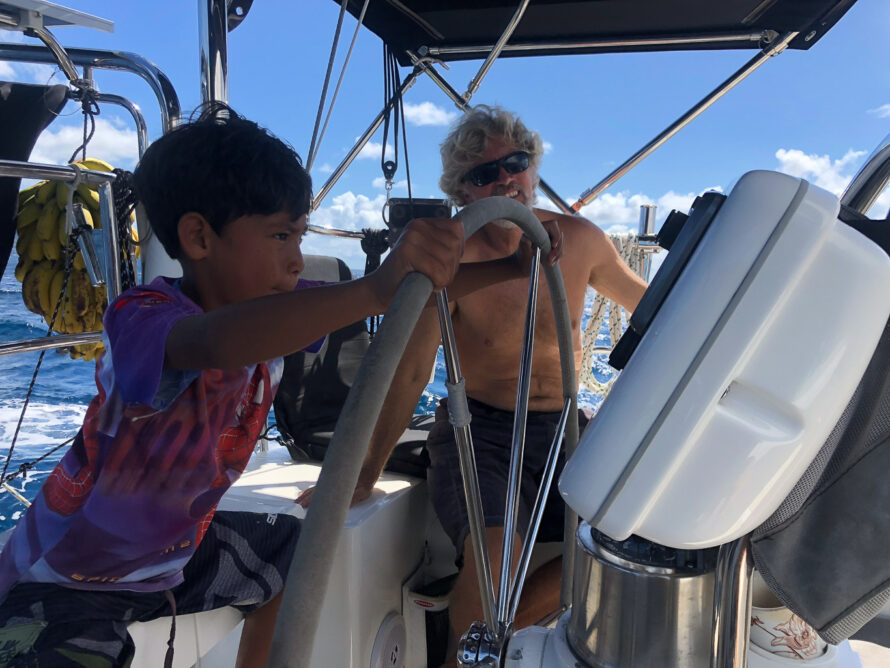

Haley and Liam tuck comfortably into life aboard Allora (Liam, knees slightly bent). Plans yield slowly to late mornings and less ambitious days. Scuba to snorkeling. Rainbow Reef in Viani Bay slips in and out of sun, turtles, schools of shimmering reef fish, clown fish in the anemone, moray eels, turtles, the odd Whitetip reef shark, luminous damsel fish and blue stars. Kids swim out from the beach for a visit, photo ops diving from the swim step. ~MS

At the turnoff to the natural waterslide where the taxi drops us is Taveuni’s prison set on a the green hillside, palm trees and a view, orange clad inmates wave Bula, Bula! The guidebook suggests that if locals are not using the slide, the water may be too high from rain to be safe. It doesn’t say anything about what it indicates that the locals are riding the slide on foot and doing flips into the pools. We were happy for Liam to go first, and appreciated the tips about hidden rocks along the fast and sometimes painful ride. ~MS

Farkle games at night reminded us of days in New Zealand when we lived in the same town. Casual dinners, walks without destinations. Just being in the same place without plans is the best part, rain or shine. ~MS

Each visit from friends and family has a certain ‘flavor’ and when Haley and Liam are aboard, it’s about EASE. They are gracious and lighthearted, generous and fun. We have a sense that we can just BE without fuss – and these days, I especially appreciate that important lesson. ‘Vinaka vakalevu’ for the inspiration, you two! And for creating the space in your lives to make the trip! ~DS

Farewell New Zealand, we fell in love …

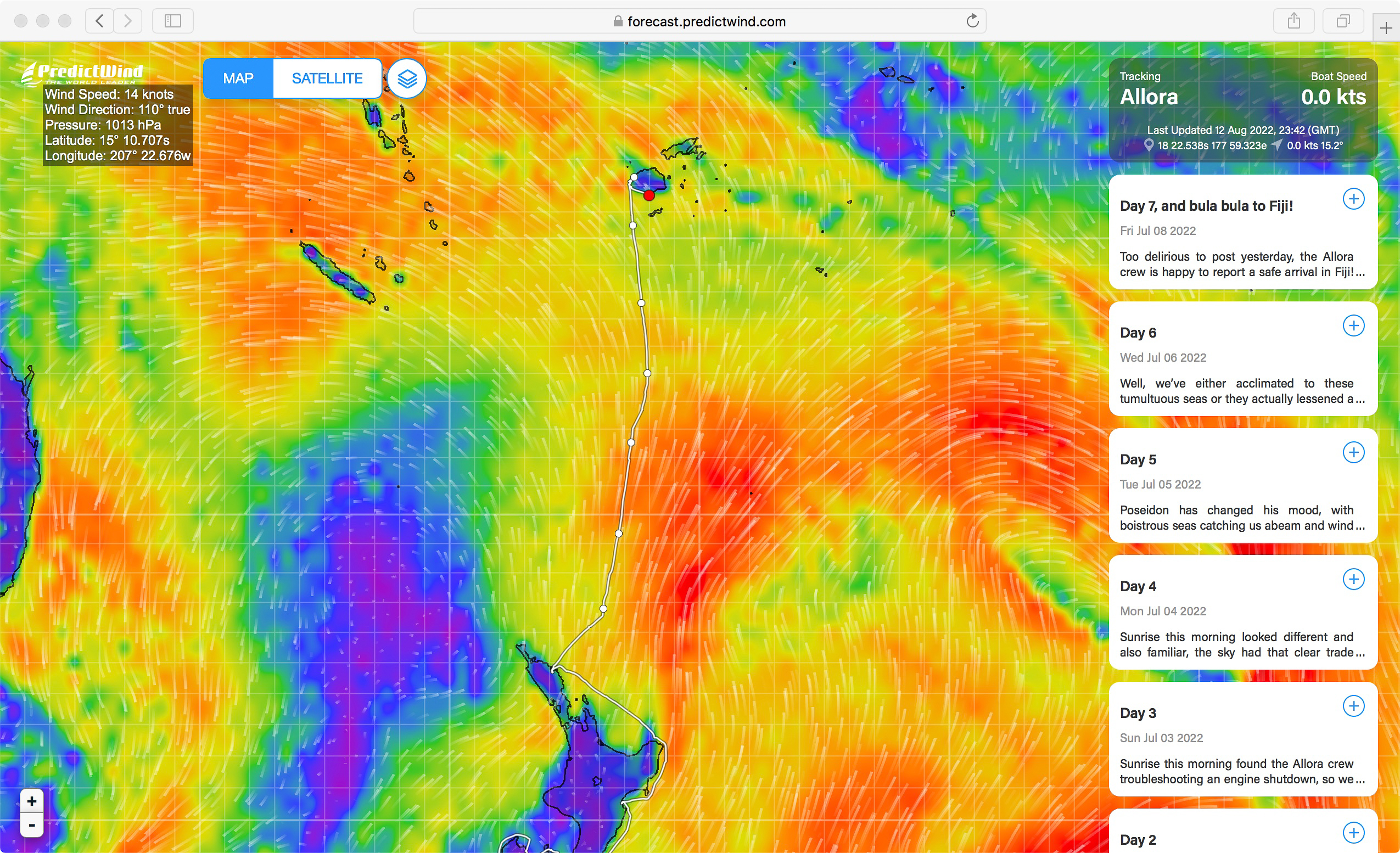

Passage to Fiji

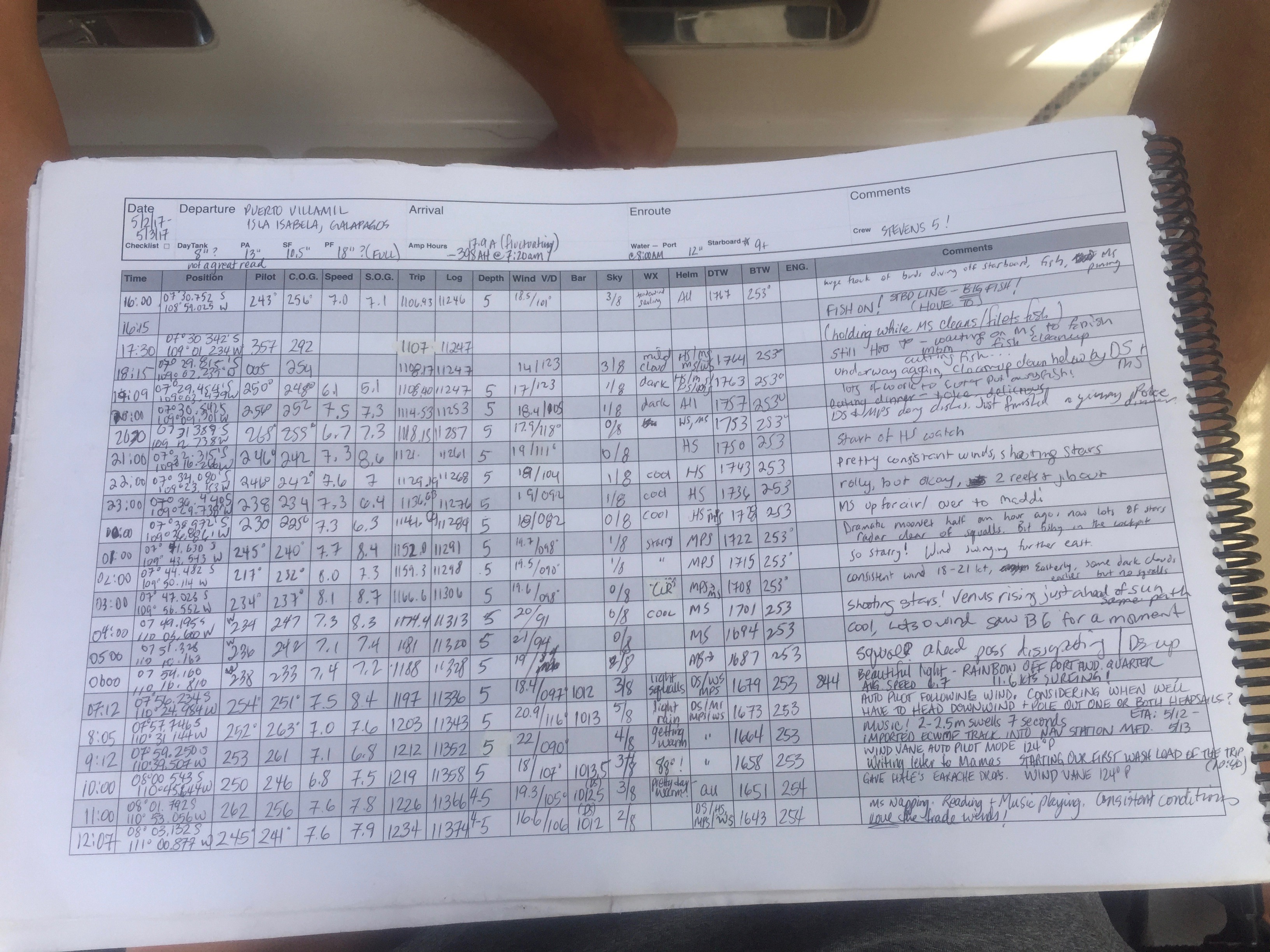

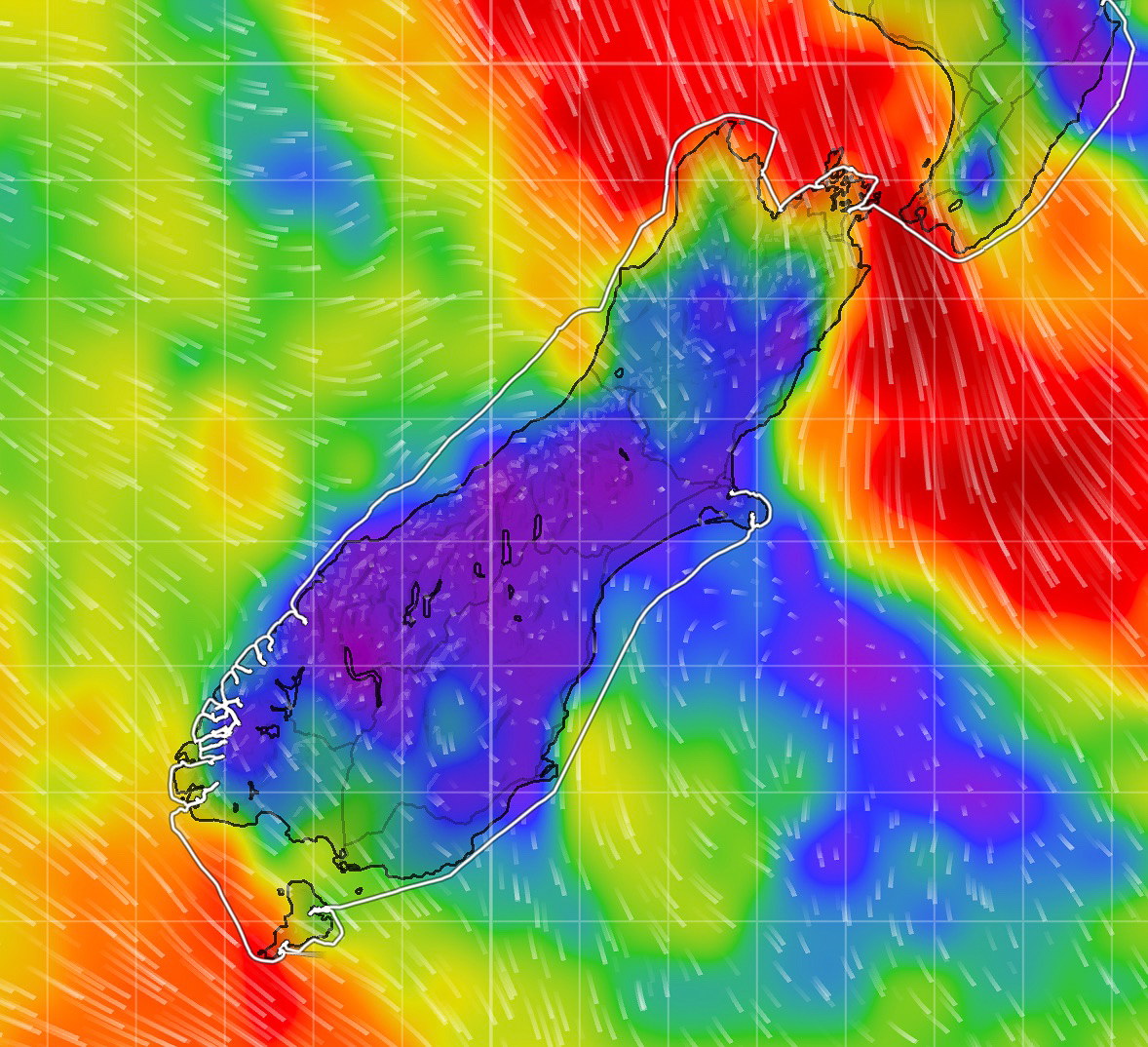

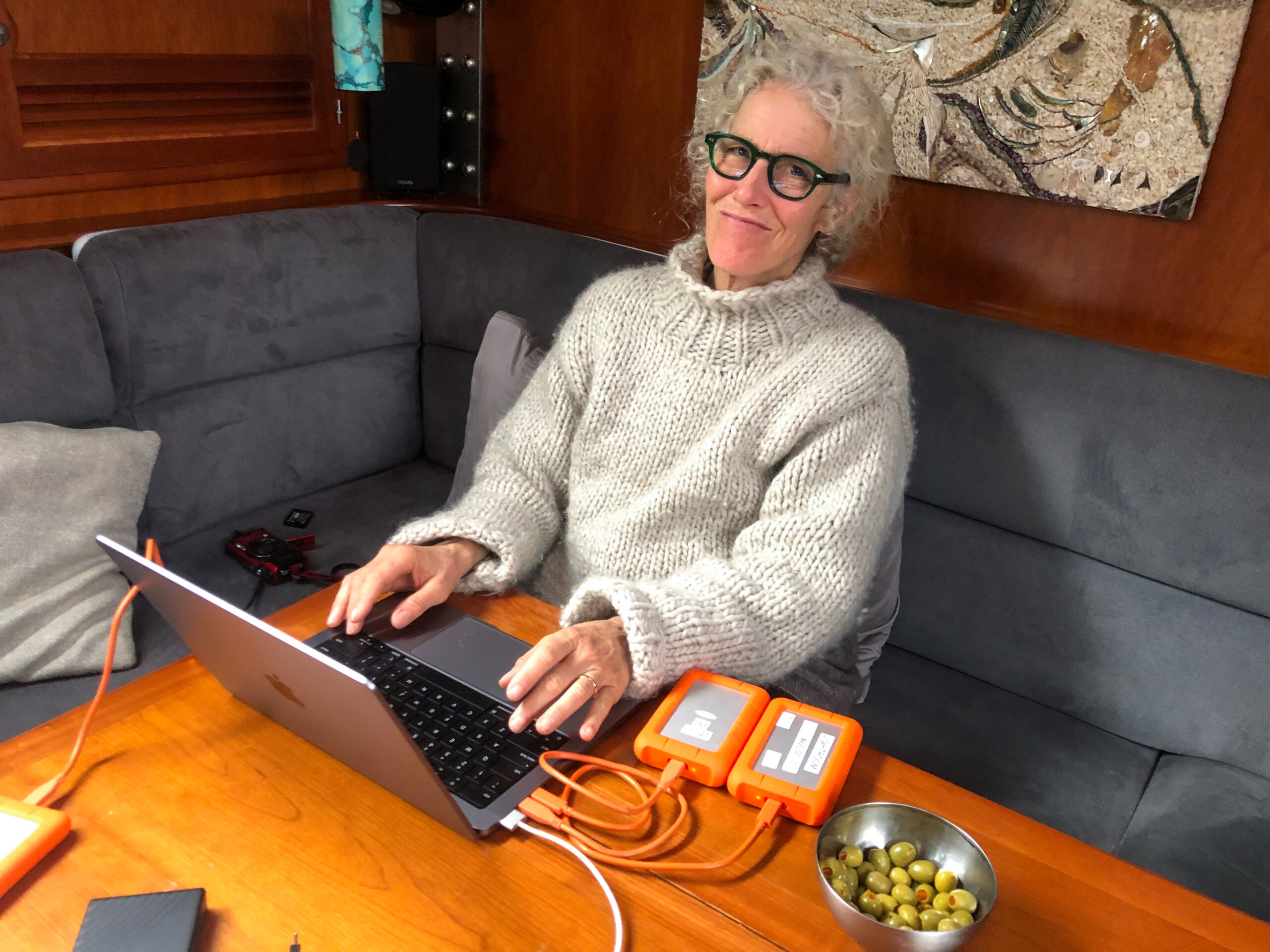

Words we used to describe this passage upon arrival in Fiji when asked by the manager of Vuda Marina (pronounced Vunda): boisterous, lively, bumpy, rambunctious. Our passage was probably pretty typical, as good as you could reasonably expect from Opua to Vuda Point, Fiji. We left on the very day our fourth consecutive visitor’s visa finally expired! New Zealand took such good care of us throughout Covid, but the time comes when even the most charming guests need to be encouraged to abandon the couch and find some new friends. We departed on the end of a passing front, which meant strong (up to 42kts) SW winds kicking us on the tail. Diana posted these notes via Iridium to our tracker.

“You would have thought we were eager to leave NZ – the way Allora shot out of the gate and rode the tail end of a ‘low’ with 3+ meter waves and up to 42kts of wind! We’re now 24 hours and 175 nautical miles in, and the seas are showing a trend toward easing with the wind. Currently on a port tack paralleling our rhumb line. The guitars have just come out and “I Can See Clearly Now!” Highlights: bioluminescence, Albatross, slightly warmer temps and Maddi as crew (just one night watch each, woohoo!”)

We hoped for maybe a day of wind to push us along, but we were lucky as the winds held out for almost two. You hear about the occasional passage with wind the whole way, but the horse latitudes aren’t called the horse latitudes for nothing… well actually there seem to be a quite a few theories about why they’re called the horse latitudes, only a couple of them to do with the paucity of wind. The basic idea is that this is where the easterly trade winds peter out, but is also the normal limit of frontal systems and westerlies in the mid-latitudes. Makes sense if the wind is going to switch from West to East that there should be some dead space between. We motored for just under twenty-four hours (we thought it might be as much as two days) using our 80 horses to get us through. We’re not big on running the engine (the noise gets tiresome and makes guitar playing tough), but we did enjoy the calmer seas, and the increasingly warmer night watches.

On my watch, just after dawn, just as I was about to shut the engine off and rally the troops to hoist the code zero, the engine made a loud screech and shut down without any warning beeps or anything. What followed was a gorgeous day of sailing in light beam winds with the big sail out that was a bit sullied by time spent trying to figure out what was going on with the engine. We suspected a transmission problem as there have been signs of impending doom for a little while, but we didn’t want make things worse and break something further, by trying to start it up until we could eliminate the possibility of water in the cylinders. I exchanged a few texts with the Yanmar guy in Lyttelton, Brian, who by good fortune happened to be at his shop on a Sunday, and he talked me through what to look for. Our mechanically minded sailor friends Ian in England (previously mentioned in this blog as the man with a plan) and Mark from Starlet both responded promptly to our SAT phone email with gearbox advice that was invaluable. I’m sure anyone can imagine how good it feels when you’re hundreds of miles out to sea, to have friends like this to turn to. Later, the Fijian mechanic showed us pictures of the main bearing in the gearbox which had literally blown up (which more than explained the problem.) Why is a longer story, which I’m happy to share with anyone interested in the gory details. I promise not to take the fifth. Luckily, we didn’t need the engine until well inside the reef at Fiji. By some miracle it held together long enough to get us into the marina.

The rest of the sail, the wind was on the beam or just ahead of the beam, consitently over 20 knots with 3 to 4 meter very confused seas for the first day, which slowly moderated a little (though the wind did not) and became more regular.

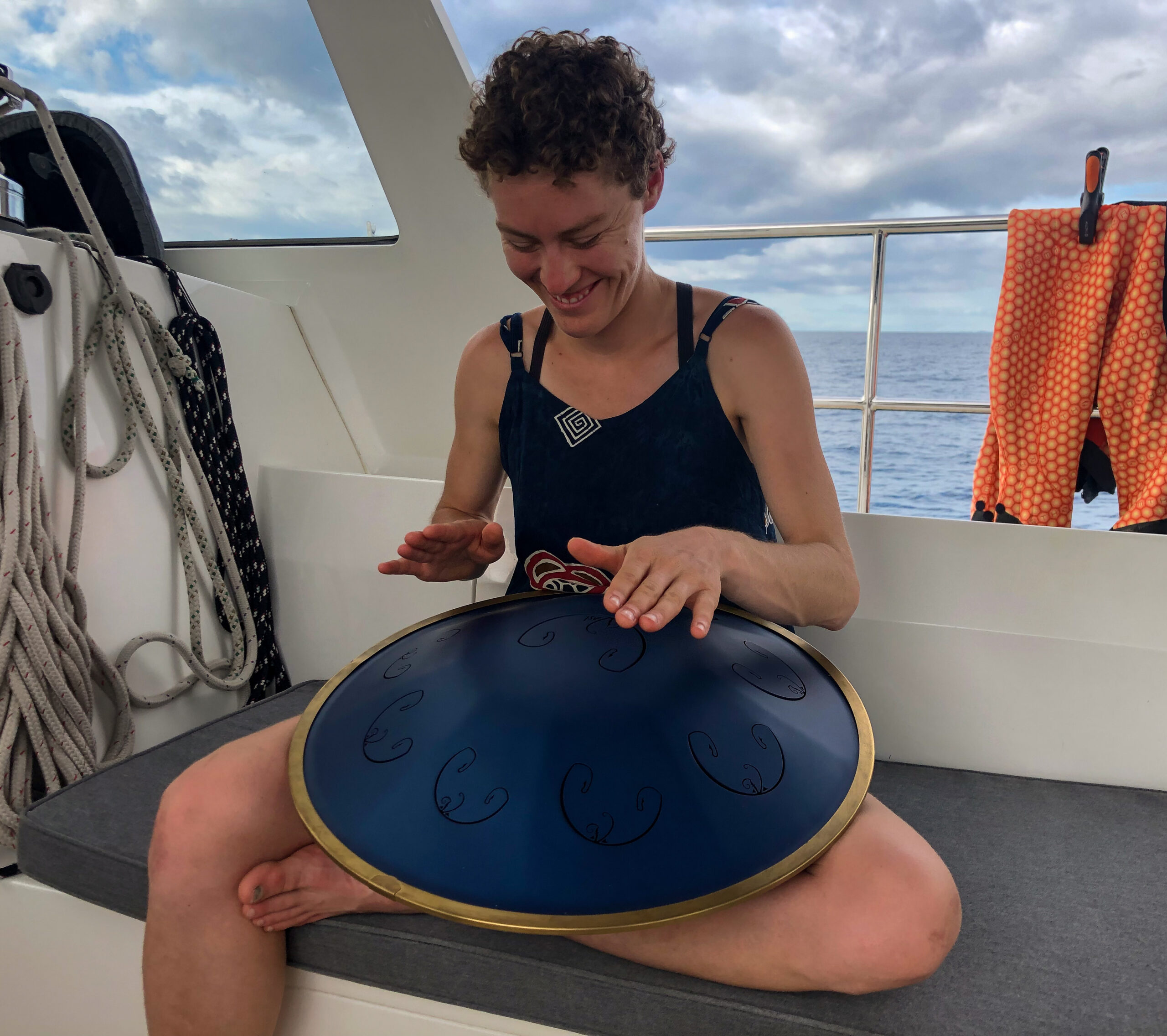

Maddi posted this note for Day 5:

“Poseidon has changed his mood, with boistrous seas catching us abeam and wind aplenty. With our course now set for Nadi, the Allora crew has spent the day either laying down or holding on tight. It’s incredible how tasks that were easy in the weekend calm have now become ludicrously challenging: making coffee, putting on pants… just want to take a pee in peace? Good luck! We keep thinking things are calming down, but perhaps it’s just our imaginations (and wishful thinking from unsettled tummies). Allora, for her part, seems to bounce joyfully over the boisterous seas, carrying us northward. The warm air, puffy trade wind clouds, and occasional flying fish among the leaping waves remind us that we’re back the tropics. We managed to brave the splashy cockpit for some music today, and only one of us took a full dousing! Heading into the night a salty crew, with gratitude for the wind and hopes for mellower seas tomorrow.”

Though our speed through water was usually pretty stunning, it was all such a sloppy mess that our actual distance made good suffered. Still we logged a couple days over 170 miles, coming in at 7 days for the whole passage. After a rowdy, tumultuous, brisk and challenging ride, the calm water inside the lagoon felt surreal, the welcome song at the quarantine dock seriously touched our hearts and the Covid tests brought actual tears to our eyes!

Maddi’s time in Fiji was already going to be pretty short, after waiting in Opua for weather, so we just couldn’t stand the idea of hanging out in the Marina, working engine or not, even though that would obviously be the prudent choice. We hadn’t seen the blown bearing yet, so blissfully ignorant, we decided that we would sail out to the reef for a couple of nights. We picked a spot that looked like we could sail onto anchor, and off, if we had to. Namo (our dinghy) was also standing by to push us along if all else failed. The wind cooperated (which is lucky because the engine quit again just after we got out of the marina and got our sail up), and though we didn’t have to sail onto anchor, we did have to manually drop it since the rough seas of passage had managed to drown a supposedly waterproof fuse box on the windlass.

The night before we had to take Maddi back for her flight, I woke up feeling pretty sick. Diana was feeling a bit off, too. She thought it was the rolly anchorage, I thought it might be bad food. By morning I was slammed. So Diana and Maddi brought Allora back without my help.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t a scrap of wind, so they motored the whole way, with Diana in deep psychic communication with the Yanmar 4JH80, to keep it together until she could get all the way in the narrow marina entrance and tied up to the circular quay at Vuda. I watched from below – first the palms of the channel drifting by and then our neighbors’ masts as she wedged Allora into her spot, bumper to bumper with boats on either side. Flawlessly executed. We realize we really need to trade jobs now and then, just to practice for occasions like this. ~MS

Arohanui South Island! Passagemaking Northward.

Picton to Opua via Napier and the East Cape (duh, duh, duh)

Diana’s last log entry on the first leg of this passage: “worst passage ever.” Maybe, I’m not sure, but I confess to getting seasick, for only the third time ever. Even so, I think the hardest part was leaving the South Island in dead calm with the threat of drizzle. After two and half years, it felt like leaving home, not least because we were leaving Haley and Liam, and knew it would be a while before we could get back.

Fueling up, (which for some reason is always a little stressful for me), was extra stressful knowing it was the last thing to do before saying goodbye. After multiple hugs and lots of tears, there was nothing to do but cast off the lines and pull away.

We were on a bit of schedule, running out of time to get to Opua before Maddi arrived from the States. Also, it was crucial to time our exit from the Tory Channel for a reasonably favorable current, the basic recommendation was leave on high tide out of Picton. We led that by an hour or two to try to avoid encountering head winds in Cook Strait. It was pretty mild to start and Diana made some super yummy wraps for lunch (she is the undisputed Empress of wraps in my book). As seems to so often be the case sailing around New Zealand, there was no chance of entirely missing the wind shift, and about halfway across we were sailing close-hauled. At least the seas, at that point weren’t too bad, not stacking up against current or anything. I went down to take a nap, and missed Diana logging 13 knots surfing on seas that were getting pretty steep. In fact, we wandered into the edge of an area of rip tides and overfalls, ‘Korori Rip,’ that was pretty dramatic. As it got dark the wind was on our beam and so were the steep seas. Diana was feeling pretty awful, and then I got sick too. This might have been where Diana logged “worst watch ever,” – she was really feeling bad and then the rudder on the hydrovane (our wind vane steering system) came off and started pounding on the stern. It took Diana a couple minutes to figure out what was going on, what the loud noise was. I donned a PFD, clipped the harness in and took a knife out onto the swimstep, hoping that I could cut the safety line off without losing it. It was pretty wet, but I didn’t want to take time to put on boots, so I opted for bare feet. Anyway, it actually wasn’t that bad, Diana has set up holder for a good sharp dive knife and a pair of pliers under the lid of the lazarette where they are super handy (she’s pretty good at coming up with that kinda stuff). I took the next watch and Diana tried to sleep off her seasickness. Once we cleared Cape Palliser things improved dramatically.

No doubt timing arrivals, departures, capes and channel entrances can be the trickiest part of sailing. You’re always trading one ideal for another. The next challenge of this passage was the East Cape, which is massive and takes a couple days to fully round. The forecast was for 4 meter seas and forty knot gusts… not super inviting. We liked better the sound of a snug marina slip at Napier to wait for the weather to ease up a bit, but that meant arriving at midnight, which is something we are loathe to do if we’re not really familiar with the layout. It’s never nice to feel like your options are bad or worse. As it turned out, the wind in the harbor was still and the passage in, though shallow, was well marked and very well lit. We glided to the visitor’s berth next to the travel-lift, easy peasy. The quiet and calm felt glorious.

Waiting for the gale at the East Cape to ease came with a trade off — the near certainty that we would have to pass through a frontal system to reach Cape Brett. Yeah, I know, a lot of fretting about capes, but there’s a reason so many of them are given awful names by sailors (Cape Fear, Cape Runaway, Punto Malo, Cape Foulwind), they really do run the show. In the meantime, that lay two days in the future. We rounded the East Cape in the early morning, jibed and then enjoyed a glorious daytime sail headed northwest, pretty as you please, even got the guitars out for a little music.

The squalls started with darkness (naturally). Note to self: frontal passages are not to be taken lightly! Also I’m going to try to remember that the forecasts don’t really represent true wind speeds in these conditions. These are more like what you get with squalls in the tropics (sudden doubling of wind speeds) but over a much more sustained area and time period. Soon we were double reefed on main and jib, taking big seas over the whole boat.

Once again, Diana took the hardest watch (you might accuse me of scheming here, but I swear this is just a matter of chance). Her words from the log: waves over bow, raucous, deluge, still dumping. Mine: rain, clearing, wind finally calming. At least I tried to make up for it giving her a longer watch off, putting in four hours to clear Cape Brett. All the while looking forward to the forecast easing and a swing of the wind for a quiet sail into the Bay of Islands. No such luck. Wind died, and then the engine died, 8X according to Diana’s notes. At 5AM I was back on, and eventually the mystery of the engine was solved. I was so focused on the last engine issue back in Fiordland (which was entirely electrical) that it took me a while to realize that the current problem was oil pressure. I’d checked the oil, but with a heeling boat, the reading was off. I added oil and the engine was happy again. More engineering-inclined-sailors than I have expressed skepticism about black boxes (computers) on marine diesel engines, but for the less mechanically minded (yours truly) they can actually be a life saver. Better the engine shut itself down than damage something, though it’d be kinda nice if the $1000 panel offered something a little more elucidating than “CHK ENG.”

Dawn came quietly, and it worried me a little to see fog along the coast, but it dissipated as we arrived, and pulled into a quiet slip in the Bay of Islands Marina. ~MS

Abel Tasman to Waikawa Marina, Queen Charlotte Sound

Passagemaking: Milford Sound to Abel Tasman National Park, South Island/NZ

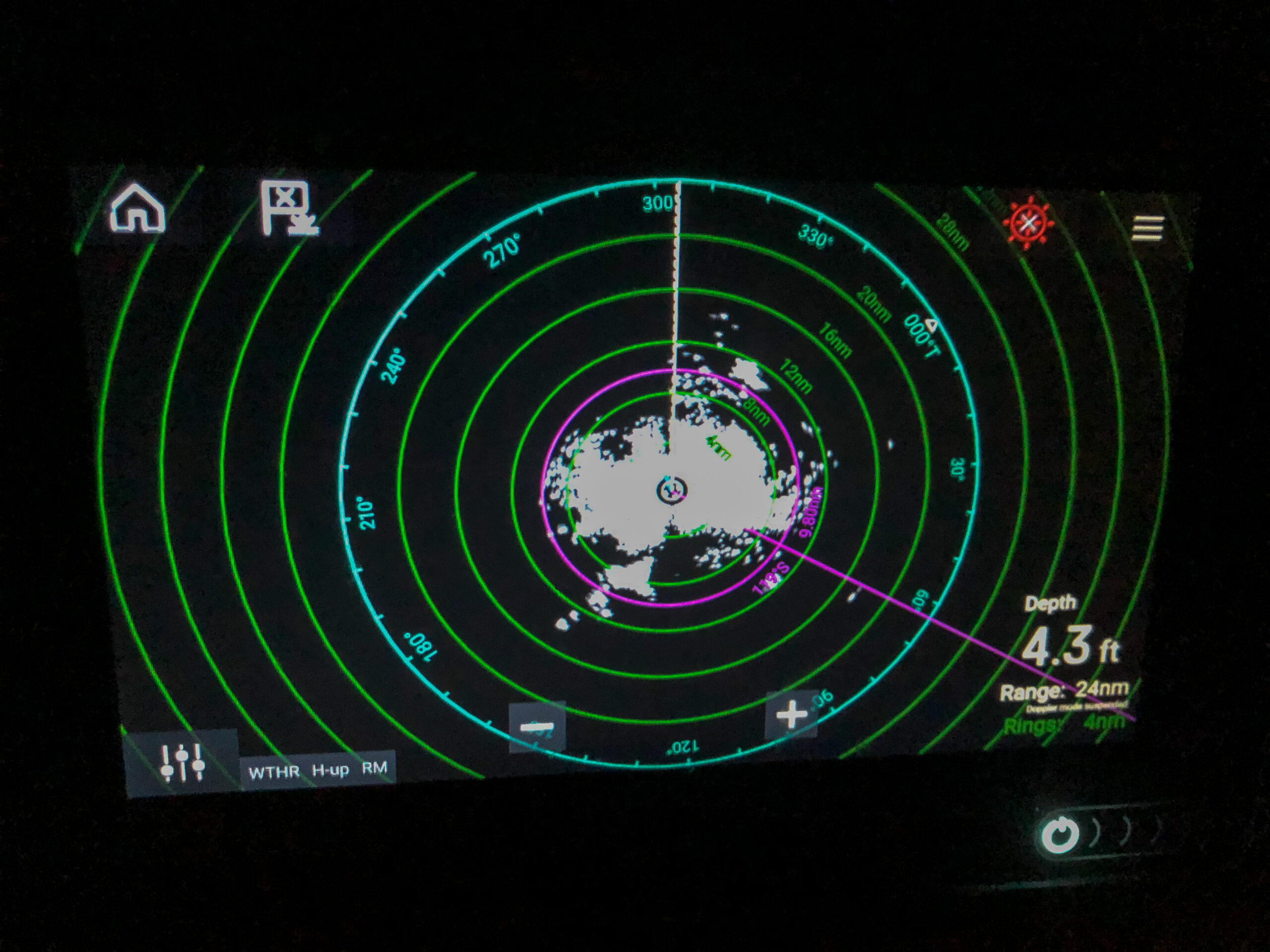

It was a bit spooky sailing out of Milford at midnight without a moon. We had our inbound tracks on the chartplotter to follow, but it’s pretty amazing how disorienting darkness can be, even for feeling whether to turn to port or starboard to follow a line. Also with the steep granite walls, we didn’t feel 100% confident in our GPS. Diana went to the bow, and I stepped away from the helm to try to orient myself every few minutes, as we moved cautiously down the fiord. Though the GPS did seem to have a decent idea about where we were, it was also reassuring to have radar confirming the distance to the rock walls on either side. But what helped me relax most at the helm, was when Diana shouted that the dolphins had come to escort us out. I leaned over the rail and could just see and hear them splashing off our port headed for the bow. It was hard not to feel like they’d showed up intentionally to reassure us.

One of the many challenges of the passage from Milford up around Cape Farewell into the Cook Strait, is that there is only one place you might possibly stop, but that requires negotiating a river bar entrance at Westport (just north of Cape Foulwind!), which is safe only in decent weather. Otherwise, it’s a solid three day run (if you keep your speed up), which just barely fits into the cycle of weather shifting from South to North. The weather window that presented itself to us seemed pretty typical, catching the end of a southerly, motoring and motor-sailing through variable winds in a race to meet the Cape with relatively light winds rather than the usual NW or SE gale.Leaving sooner, we’d have had more wind to sail with, but we’d risk arriving too early for the switch of winds at Cape Farewell.

Diana took the first watch just after 2 AM after we cleared the hazards on the north side of the entrance to Milford and could head more directly north. “Really cold, icy hands,” she wrote in the margins of the logbook. “Overcast skies heading further out to clear Arawua Point/Big Bay Bluff.” Just after sunrise on my watch, I got a glimpse of the mountains south of Mt Aspiring, which reminded me of Wyatt’s 100 mile run the length Aspiring National Park. I wondered if he could have seen the Tasman Sea from any of those lofty ridge lines he traversed?

Also in the logbook, I see a lot of scribbles in these notes about fuel rates, and estimates of actual fuel burned for miles ‘made good.’ Allora carries 190 gallons full which is more than enough for the distance as long as the weather is reasonably cooperative, but it makes a difference if you’re burning 1.5 gallons/hour or pushing the engine and burning 2.5 gallons/hour. The extra gallon doesn’t double your speed. People better at the maths would probably be able to calculate exactly what fuel rate is most efficient. I settled upon 1.6 or 1.7 as an nice compromise of efficiency, speed (to make our date at Cape Farewell) and comfort.

We had rain. We had current steadily set against us. We had dolphins streak by in the night leaving comet trails in the bioluminescence. We fussed about the wind, almost-but-not-quite-enough to sail, ever creeping up on the nose. We almost lost a batten in the mainsail. Then later, Otto, our autopilot made a sudden decision to turn hard to starboard out of nowhere. The switch for the high pressure pump on the watermaker heated up and set off the smoke alarm (naturally at night-while I was off watch). We saw no other boats besides the occasional fishing boat working closer to shore. We caught a glimpse of Aoraki (Mt Cook) at sunset, and at Cape Foulwind a couple of seal lions waved as we passed by.

On the last night, as seems to be a theme lately, Diana drew the toughest watch of the passage. There was just no way to completely avoid a patch of heavy winds slated to meet us as we approached the Cape, straight on the nose. We tried to time it for the least possible, but Poseidon wasn’t going to let us off feeling too clever. For her whole watch, Allora slammed into 20 knots on the bow clawing her way up the last bit of coast to Cape Farewell. Finally, after calling Farewell Maritime radio to try to find out whether it was generally considered advisable to cut the corner at Kahurangi shoals (which they weren’t really able to commit to), we decided it probably wasn’t, so we slogged on. Diana went off watch and very soon after, we were able to fall off the wind. Just five degrees made a big difference. Pretty soon we were motor-sailing and by Diana’s last sunrise watch she was able to shut the engine off and sail along Farewell Spit, an amazing 25km sandbank off the northwestern corner of the South Island at the opening of Cook Strait. The winds were light but sweet. Finally! ~MS

Magical Milford Sound/Piopiotahi! – Fiordland

Piopiotahi (Milford Sound) resonates with awe and leaves us speechless, like the Grand Canyon or Machu Picchu, or the Magellanic Clouds on a vividly starry night at sea. The sheer mass and scale, the soaring beauty, each breathtaking turn. Words just pour out, but fail to capture what it feels like to sail into this magnificent fiord. The day we spent in this unique-in-the world place, was blue and lit with sun, the water impenetrably deep, granite walls towered over us, beyond imagination and comprehension, the waterfalls gushed bountifully without end. Apparently Captain Cook missed Milford on his first pass, and actually that’s not entirely surprising. Approaching from the sea the fiord begins rather humbly and then builds and builds in its symphonic crescendo of magnificence. A bit much? Not really. Every time I stepped away from the helm and out from under the dodger I caught my breath as I looked up and up. ~MS

A quick blink in Bligh Sound/Hawea, – Fiordland

George Sound/Te Hou Hou, (‘Georgious!’) – Fiordland

The run outside between Caswell and George Sounds is around 14 miles. We left early to try to beat some forecast rain and gusty NW winds, and almost made it. The rain started just as we made our turn in. Diana logged the max wind at 27.2 knots, then went down and crossed it out to a revised 29 knots. By the time the wind had blasted us another two miles down the sound, Diana had crossed that out to record 42 knots. Looking on the chart with the wind howling behind us, we were concerned if Anchorage Cove would be able to offer any shelter from this angle of wind, even though it’s listed as an ‘all-weather anchorage.’ We worried it might be too gusty to safely negotiate the narrow spot between the river bar and small rocky island. We decided to poke in and check it out if we could. Right away the wind dropped into the low twenties then the teens, which still felt like a lot to try getting into the tight spot where fishermen had set up a line we could theoretically side tie to. The rain hammered down as Diana watched from the bow for shallow rocks off the island and I maneuvered Allora in, ready to back out if we needed. Despite whitecaps just outside, the winds this close to the little island dropped to near zero and Allora was able to hover effortlessly while Diana (in the kayak) quickly tied lines on the bow and stern, getting absolutely soaked in the process. It was a kind of a crazy feeling, the sudden stillness and security of that spot with gusts in the forties not half a mile away. We wouldn’t have guessed even from a couple hundred yards out that it was worth chancing. ~MS

Caswell/Tai Te Timu Sound – the 45th parallel – Fiordland

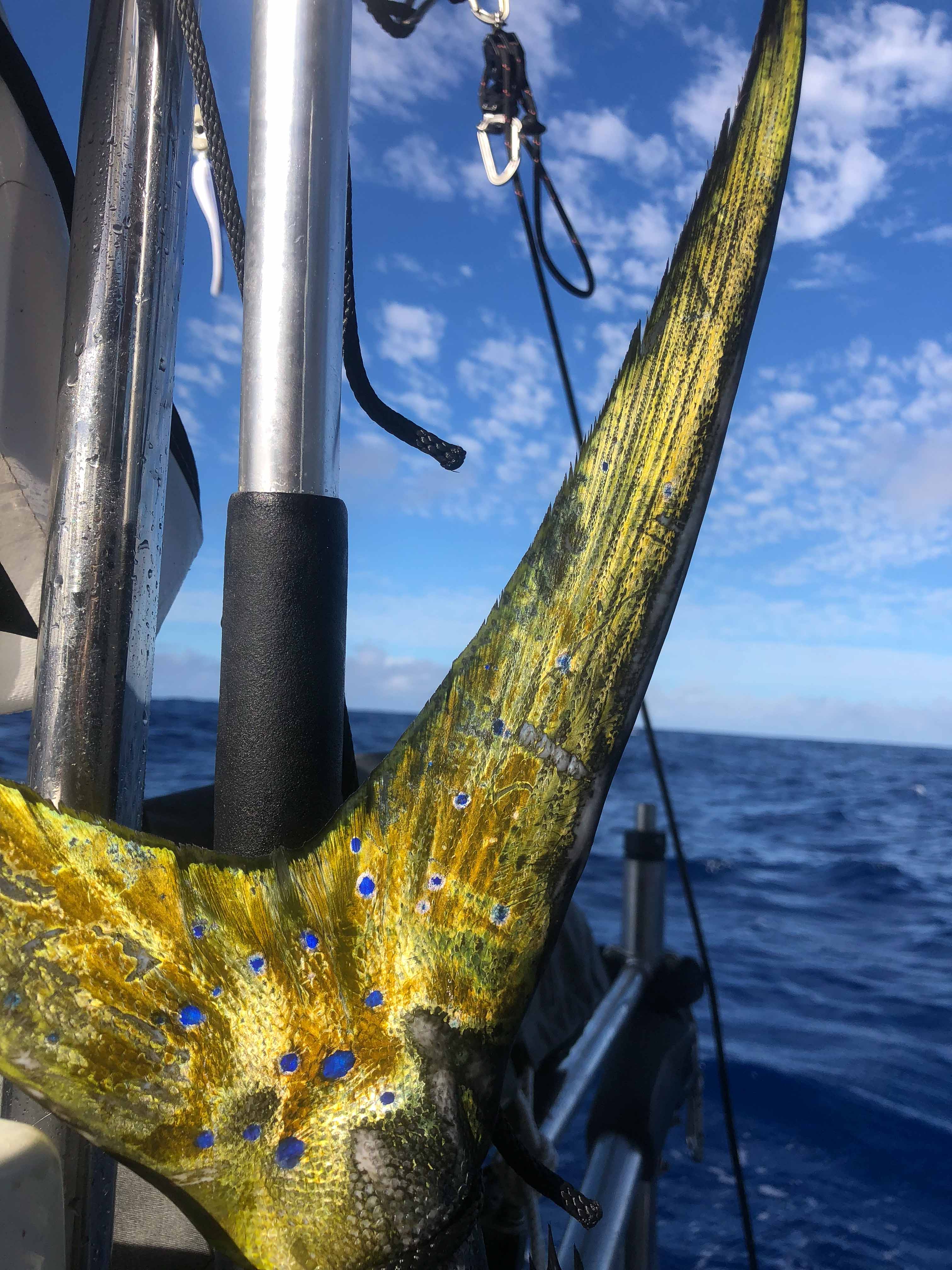

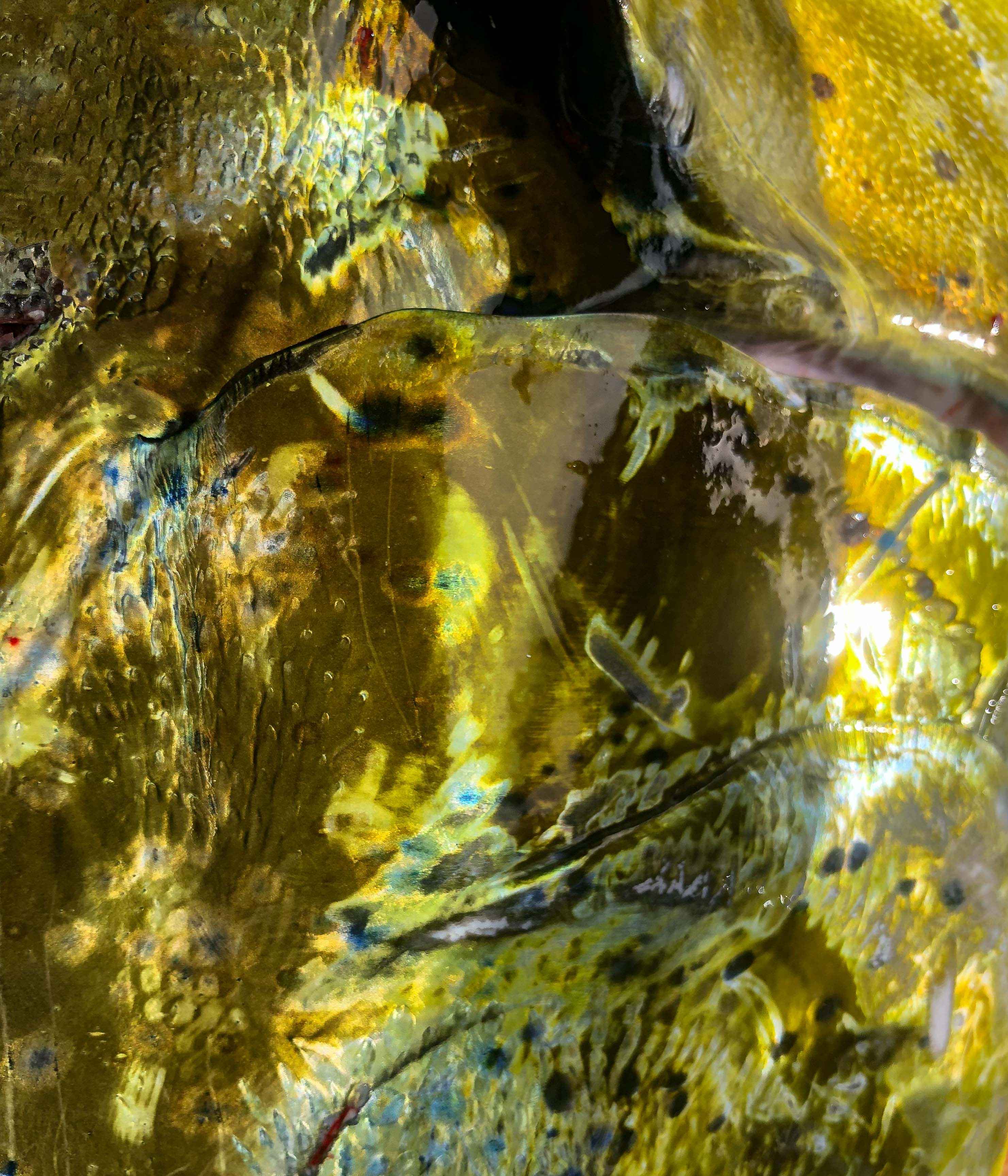

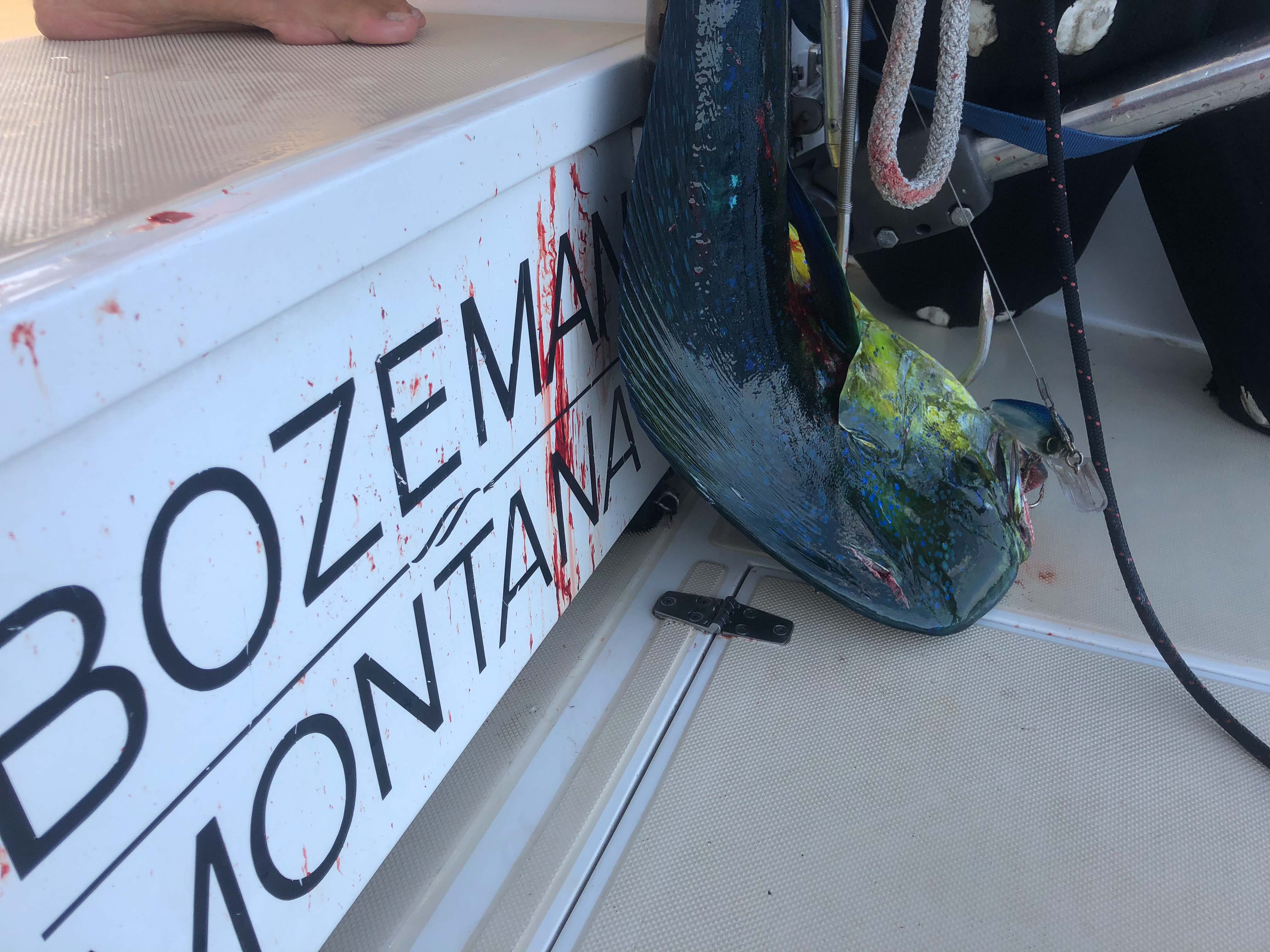

Big Fish

a big fish lived here

under this rock

in this sound

70 meters of water

down down down

finning the murky fathoms

there must be something it is like to be

a big fish

broad tail to the tide

jaw slowly moving, gills filtering

oxygen and salt from darkness

listening to the strange whirr of a prop churning distantly overhead

scent in the current

vibrations of much younger, much smaller, more foolish fish

everyone makes mistakes

joy to the world!

big fish on!

the breathless mystery of something deep

that unremitting pull of an invisible line

uncompromising bite and stick and metal barb

is there hoping it might break free

what is it like

to be another’s flesh and dinner?

exhausted thrashing on the surface

searing bright light and fierce dryness

the gaseous, ethereal world

where white birds like cherubs flitter and follow

where albatross glide like shadows of another understanding

what is it like, big fish?

now that two men hold you in firm hands

knife wielding hands

careless hands

is this the dance?

waves surge against the rocks

seaweed starfish worms green saltwater alive

o’ fish shaped wave

these men call you big fish

men who came to find things to take

big trees all in a row

is there something it is like

to be a man holding a gray dead fish

for a picture

flesh stripped from her ancient bones ~MS

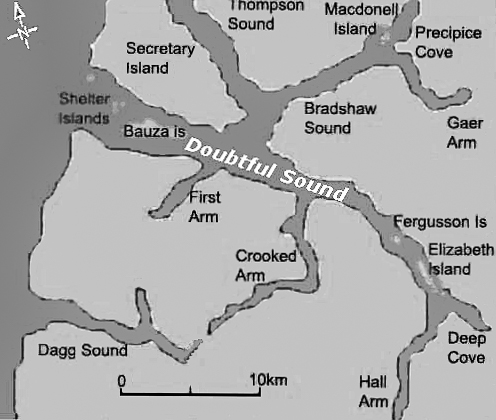

Doubtful/Patea, aka Gleeful Sound – Fiordland

Dash from Dagg to Doubtful:

The relatively short distances between sounds along Fiordland’s rugged coast allow for mad dashes timed to brief calms, but you can’t really read the ocean’s mood sheltered in the steep granite walls of the fiords. Often the designation, “all weather anchorage,” means that fishermen have figured out that even in the worst conditions, certain spots are spared. The only way to know when it’s time to go, if you don’t have the benefit of years of local knowledge, is to study the weather models that we download twice a day from PredictWind. Because they are downloading via Iridium satellite, the resolution of the models cannot be higher that 50km. So there’s a bit of an odd effect as the models average how much the wind on the Tasman Sea is slowed down by the mountainous Fiordland coast, giving the appearance of lighter winds close to shore. They probably are a little lighter compared to what they are 20 miles out at sea, but our experience is that the models generally underestimate what it’s like on the outside and overestimate what we’ll experience once inside. Wind or no, gale or no, the seas are almost always a mess, particularly where local winds funnel through the openings of the sounds. Schedules are well known as the bane of sailing but in the land based world they are unavoidable, and Wyatt had a particularly narrow window of time to squeeze in a visit to us amid preparations to leave New Zealand. So we considered ourselves unreasonably lucky when the wind that pinned us down for a couple of days in Daag, relented in perfect time for us to make the dash. We arrived at the opening of Doubtful with what Wyatt would call a ‘splitter bluebird’ sunny day. ~MS

Allora on a mooring (all by herself) in Doubtful Sound, tucked right up next to the roar of Helena Falls. Evening spent getting the aft cabin clear of STUFF to welcome Wyatt the next day. Here, I don the particular ‘happy parent’ expression, just moments after snagging Wyatt off the bus!

Yep, the same one!

Ha, Wyatt caught us both entranced!

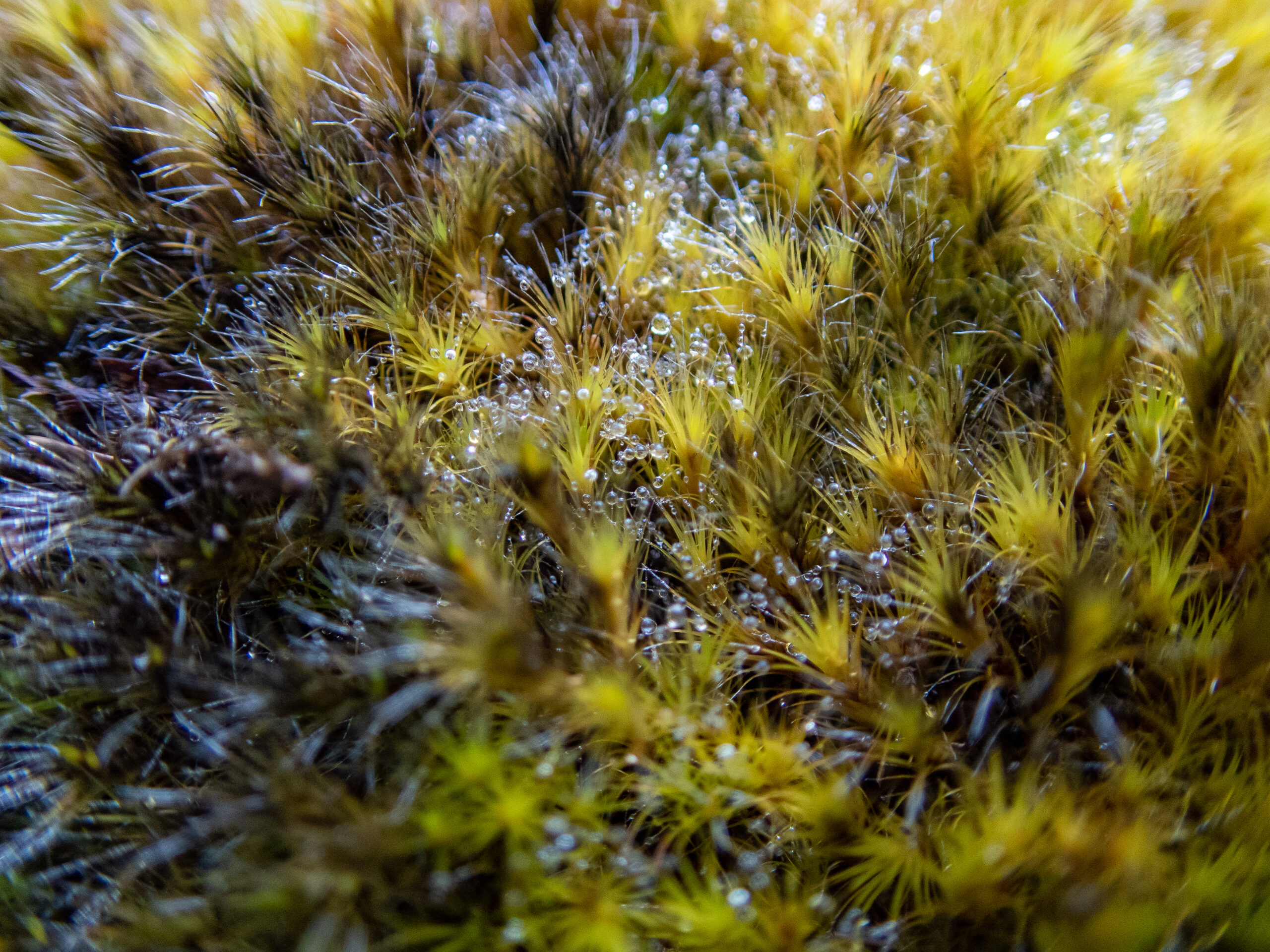

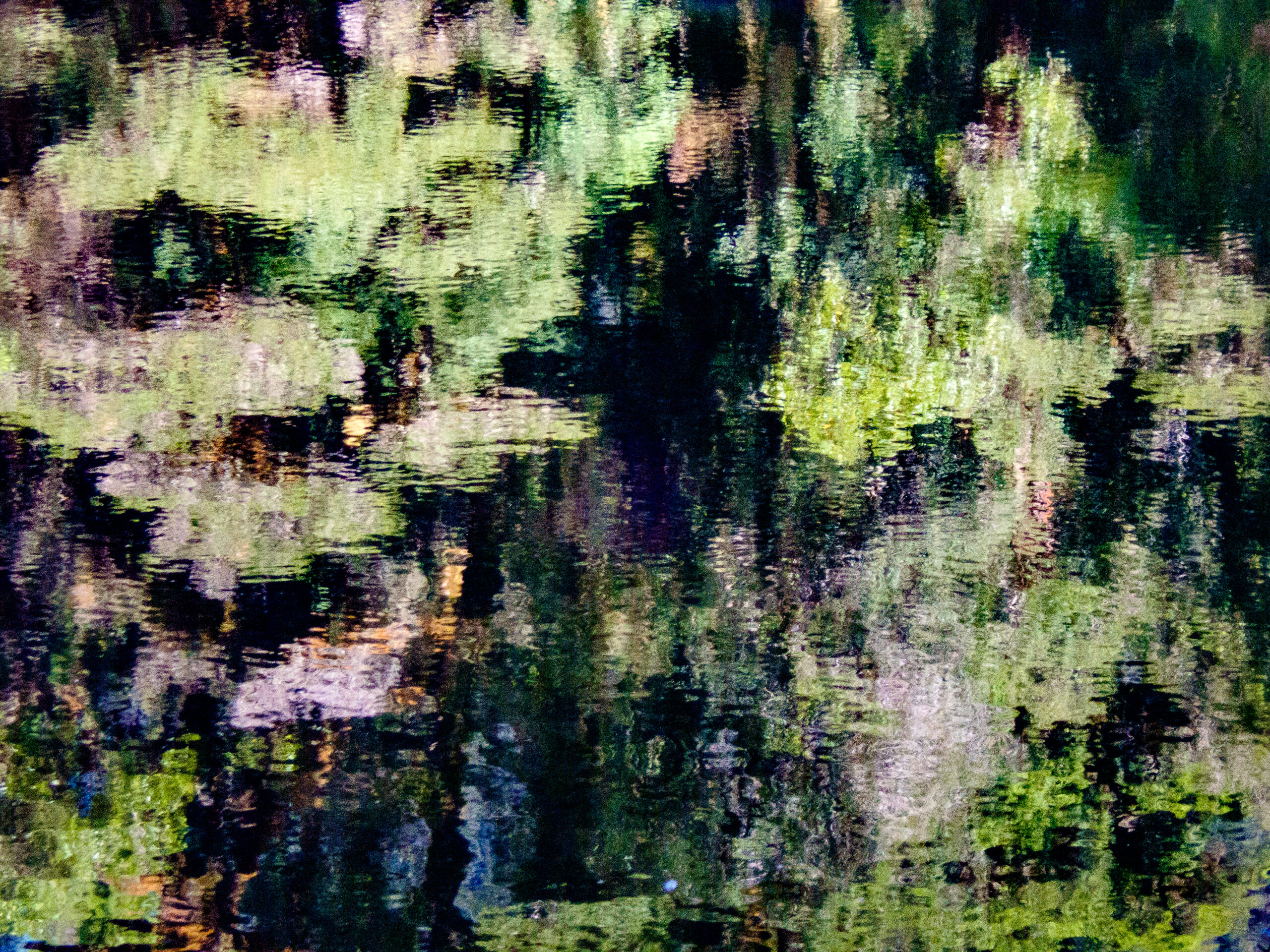

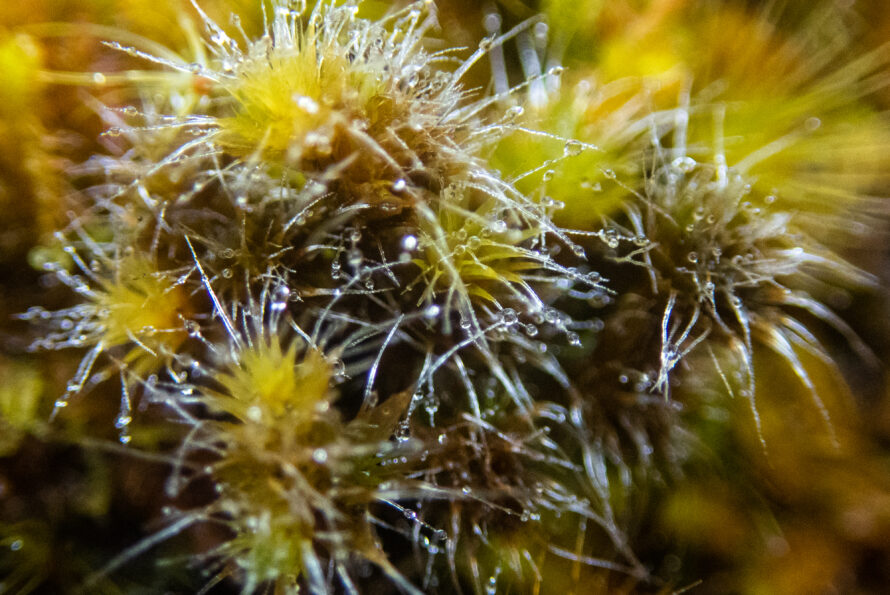

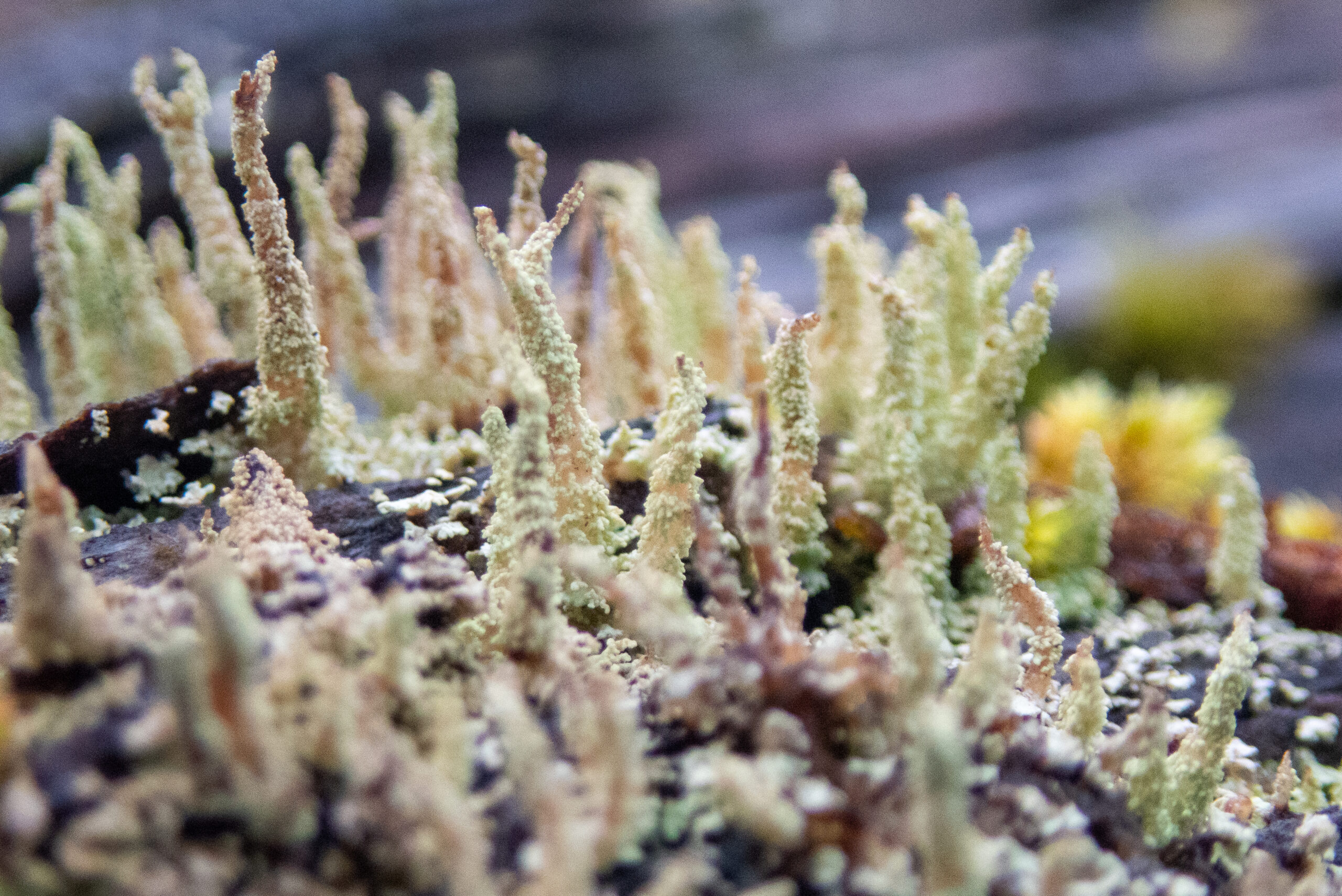

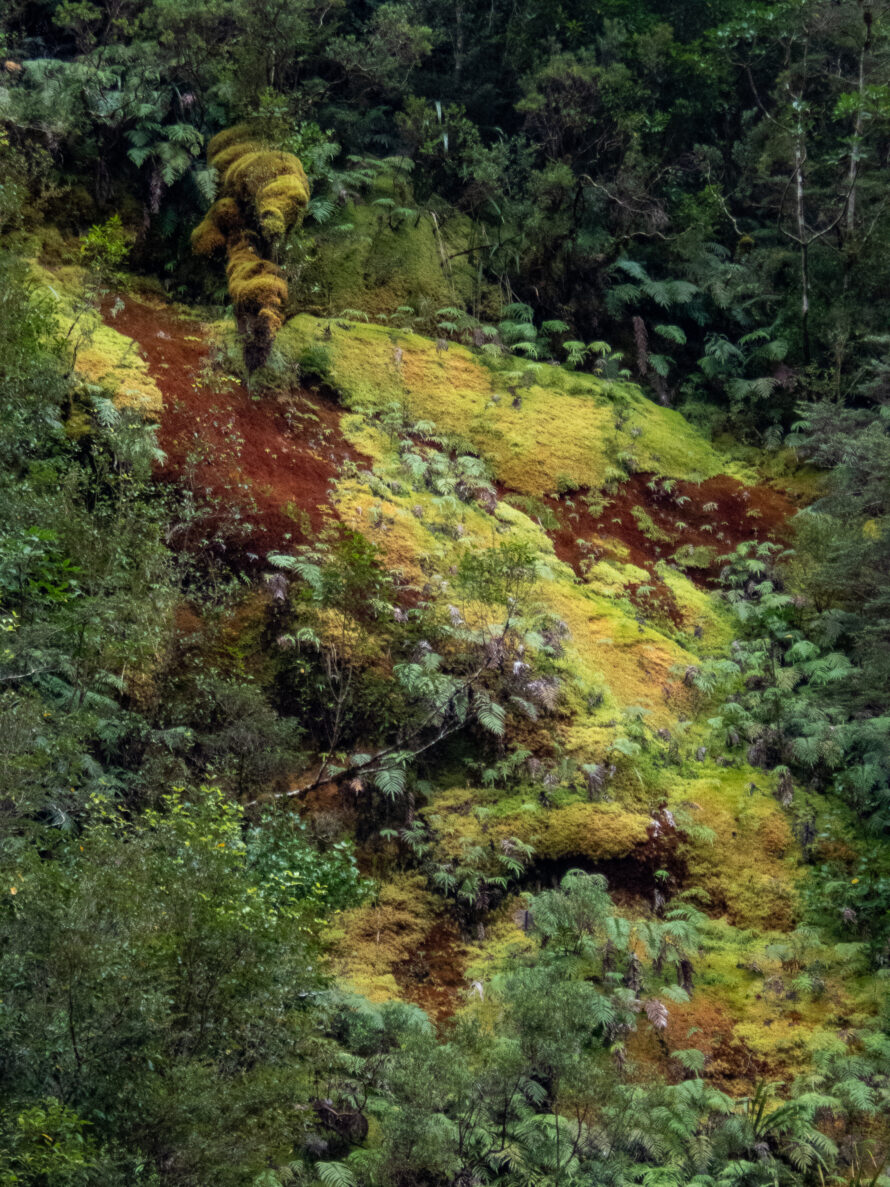

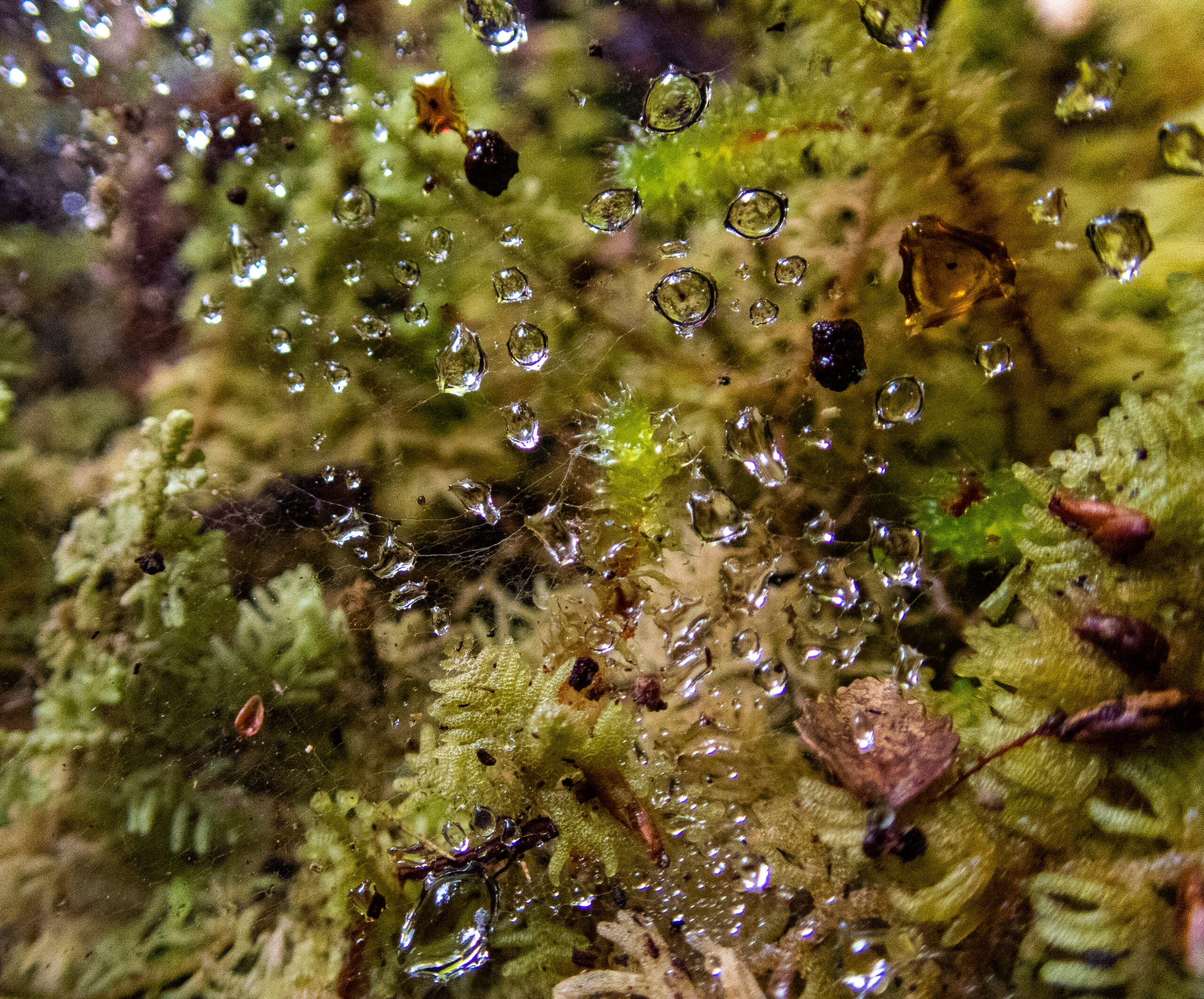

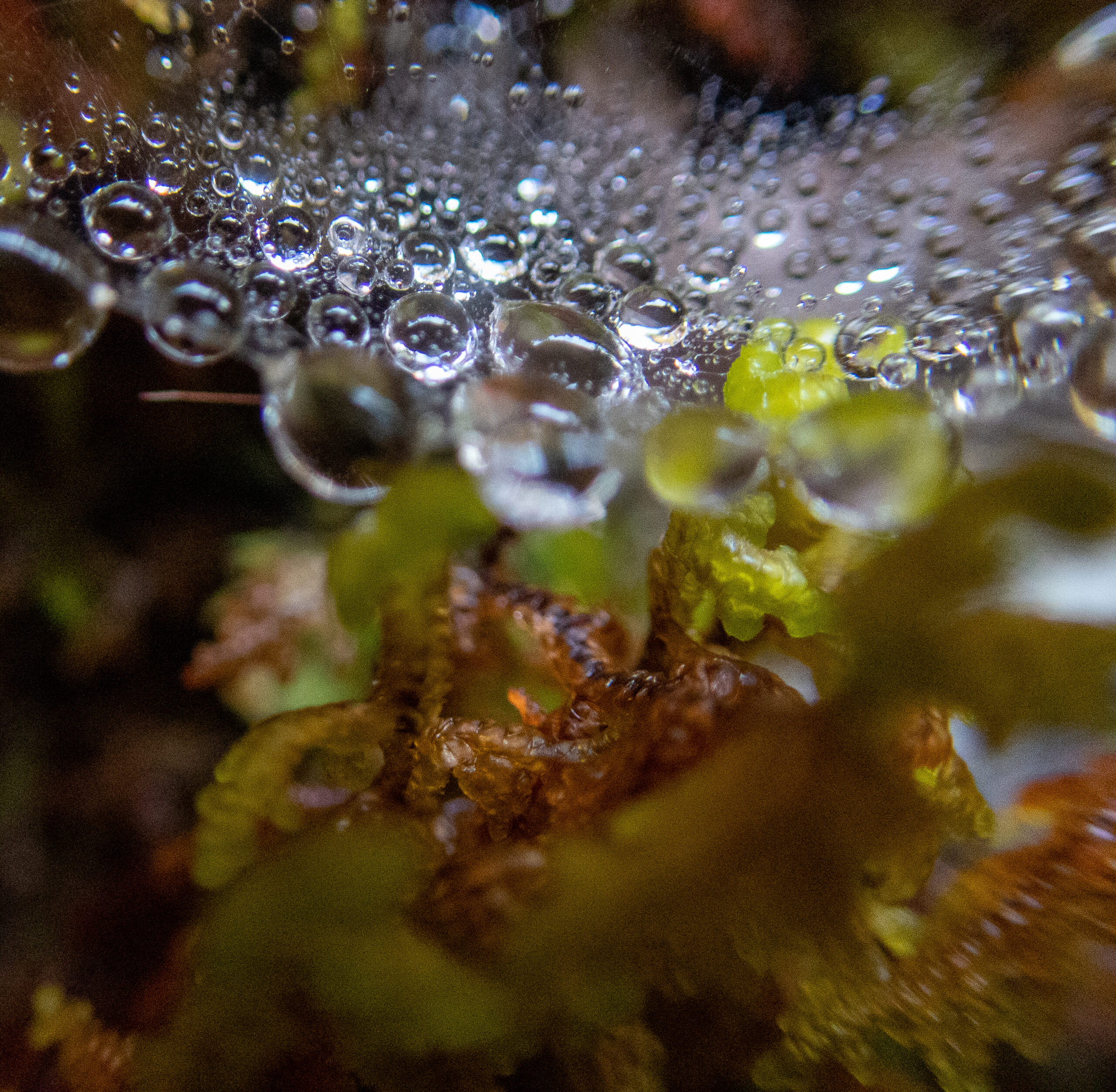

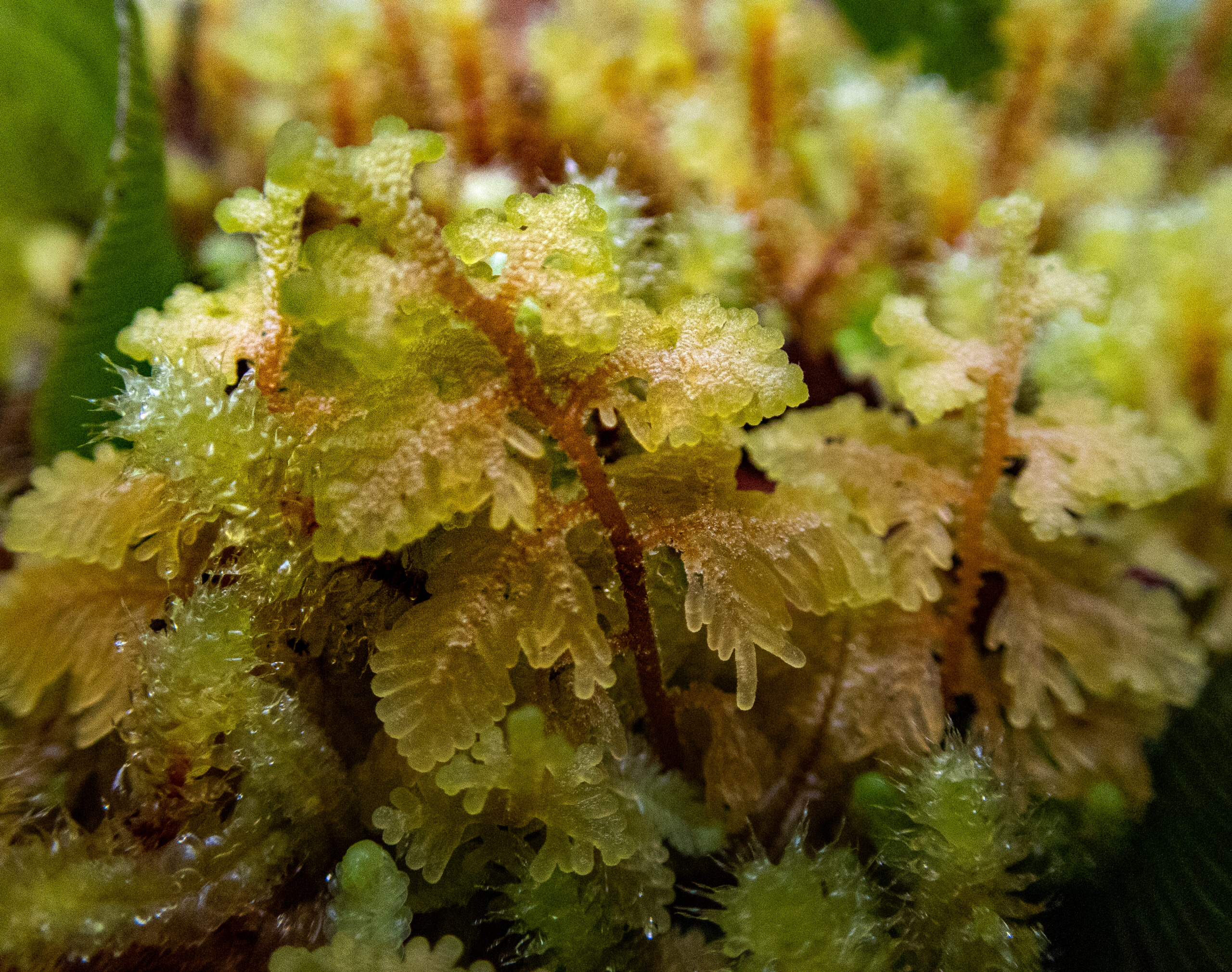

We have experienced a profound cumulative effect traveling through the wilderness of these southern fiords, as we mash through the tangled forest or glide like a whisper through glassy, watery mountain reflections. We feel a growing, deepening awareness of the liveness and power of this unfettered place. Every day Diana peers a little closer into the magical profusion of the rainforest, its tiniest creatures (or the smallest we may perceive) all this abundance of life fueled by fresh water, gray stormy clouds, shifting rays of sunlight, massive stone faces fading softly into the distance. The boundless imagination of nature is vividly accessible here, free of scheming human interference. Inexhaustible, effortless celebration. We feel blessed to feel like we belong, to participate at our particular scale, with our particular way of perceiving. Gratefully reconnected as dolphins come to play alongside Allora, turn and smile and look back at us with familiar eyes, into our own delighted gaze. As the sky softens at sunset, or looms heavy with rain before the storm, as water gushes from waterfalls that were not there before the deluge, thundering into the fiord, as williwaws tornado in wild rainbow mists across startled coves, how delightful it is to be alive, a part of, this marvelous, miraculous world. ~MS

We moved across Bradshaw Sound to Precipice Cove/MacDonnell Island, an all weather anchorage.

Still quite giddy about having one on one time with Wyatt before he flies back to the States.

Dagg/Te Ra Sound, shared only with Wapiti in the ‘roar.’ – Fiordland

‘Anchorage Arm’ and had glassy calm conditions. Instead of trying to find shallow enough depths in the middle to anchor in, we snugged up super close to shore utilizing some fishermen’s lines which are rigged in place. Wonderful protection from winds, mellifluous creek sounds and voracious sandflies!

Something happened when the twenty North American Wapiti Roosevelt gifted to New Zealand in 1905 found their way into the heart of Fiordland’s steep and impenetrable wilderness. Maybe there’s a perfectly rational scientific explanation (maybe it has something to do with crossing breeding with Red Deer?). They got a bit smaller than the fat and happy elk of Yellowstone (which certainly makes good sense given the dense rainforest) but they also changed their tune, no longer bugling with that iconic, haunting call that resonates across the frosty parklands, lodgepole forests and granite peaks of the Rockies. Our visit to Daag coincided with height of the “roar.” It’s a sound that does not “belong,” but also feels so fitting, as though giving voice to the thick ferny jungle of that unpeopled wilderness. Deep, guttural, plaintive and haunting (in their own way) – their roars echo across the still water and ridiculously precipitous canyon walls. You can hear individual stags make their way up and down the steep shore, and we paddled Namo as stealthily as we could manage along the shore hoping for a glimpse, and though they often seemed very close, we never saw them. We could only imagine their antlered heads tilted back, belly’s trembling as they gave voice to the wilderness.~MS

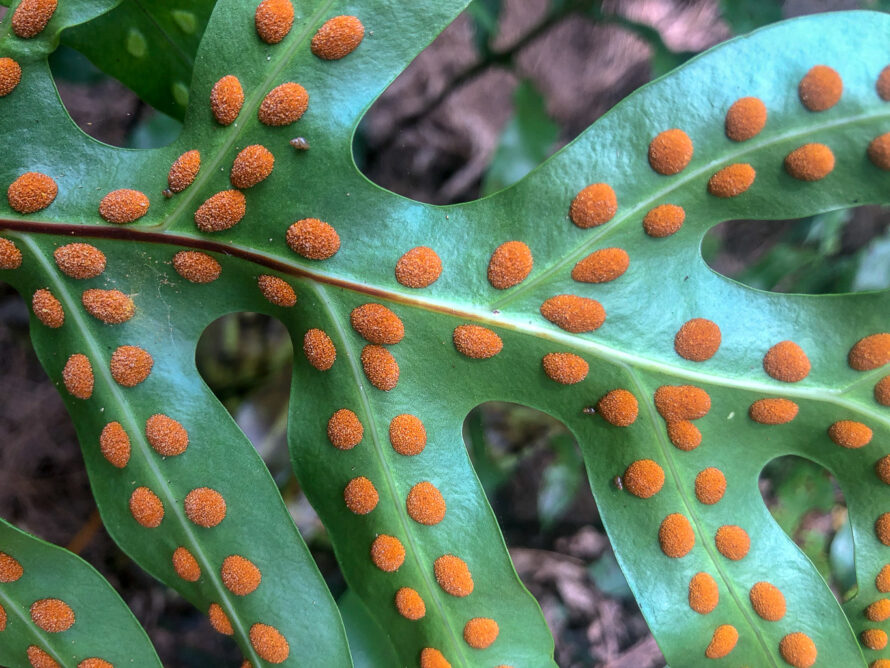

Although Spanish moss grows on trees, it is not a parasite. It doesn’t put down roots in the tree it grows on, nor does it take nutrients from it. The plant thrives on rain and fog, sunlight, and airborne or waterborne dust and debris.

Known for it’s friendly, ‘cheet cheet’ call and it’s crazy flying antics, the Fantail or Pīwakawaka often follows another animal (and people) to capture insects. Time and time again, though, they acted as guides; when we were off track in the woods, they’d appear, chirping energetically, as if to say, ‘no … not that way, THIS way!!’ I learned to always follow them!

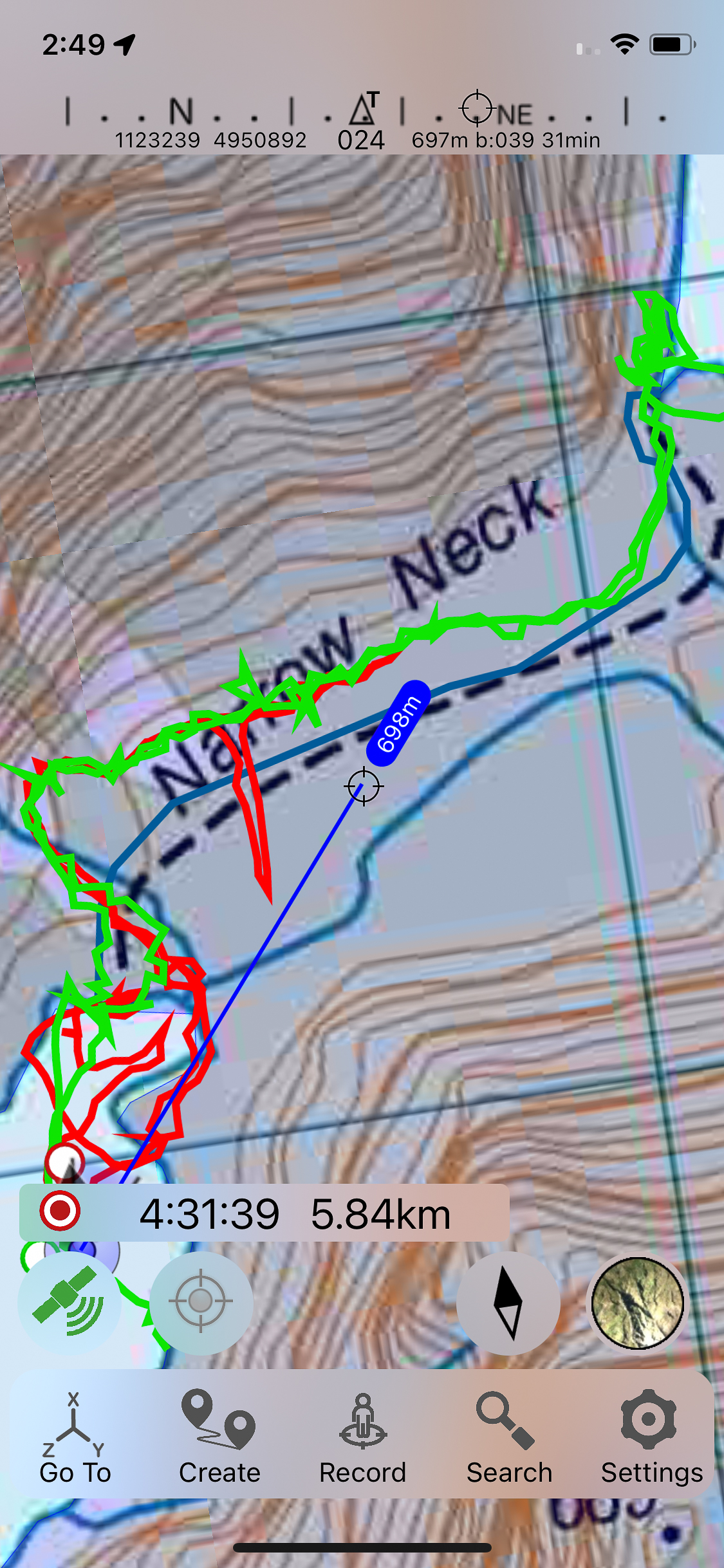

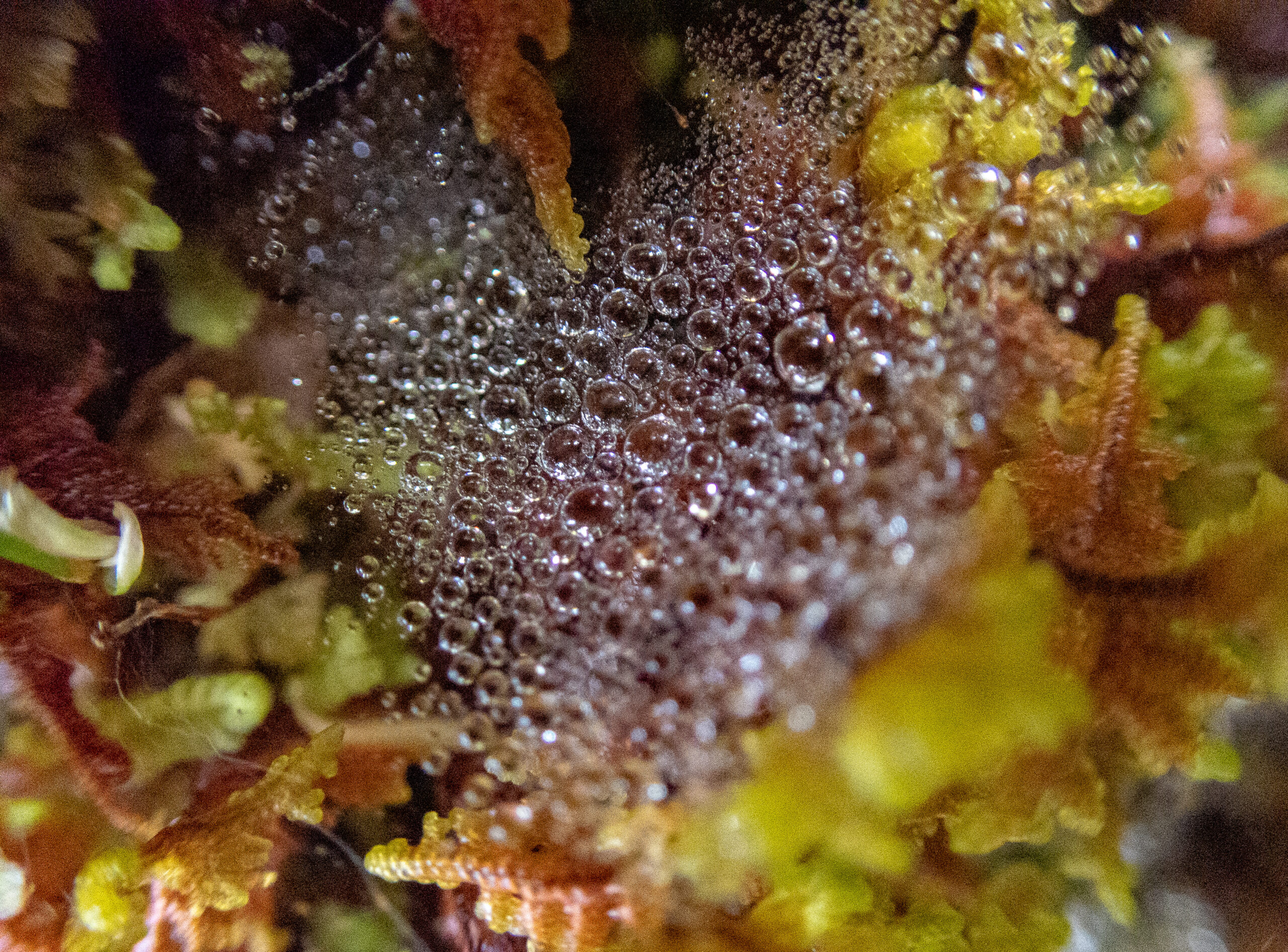

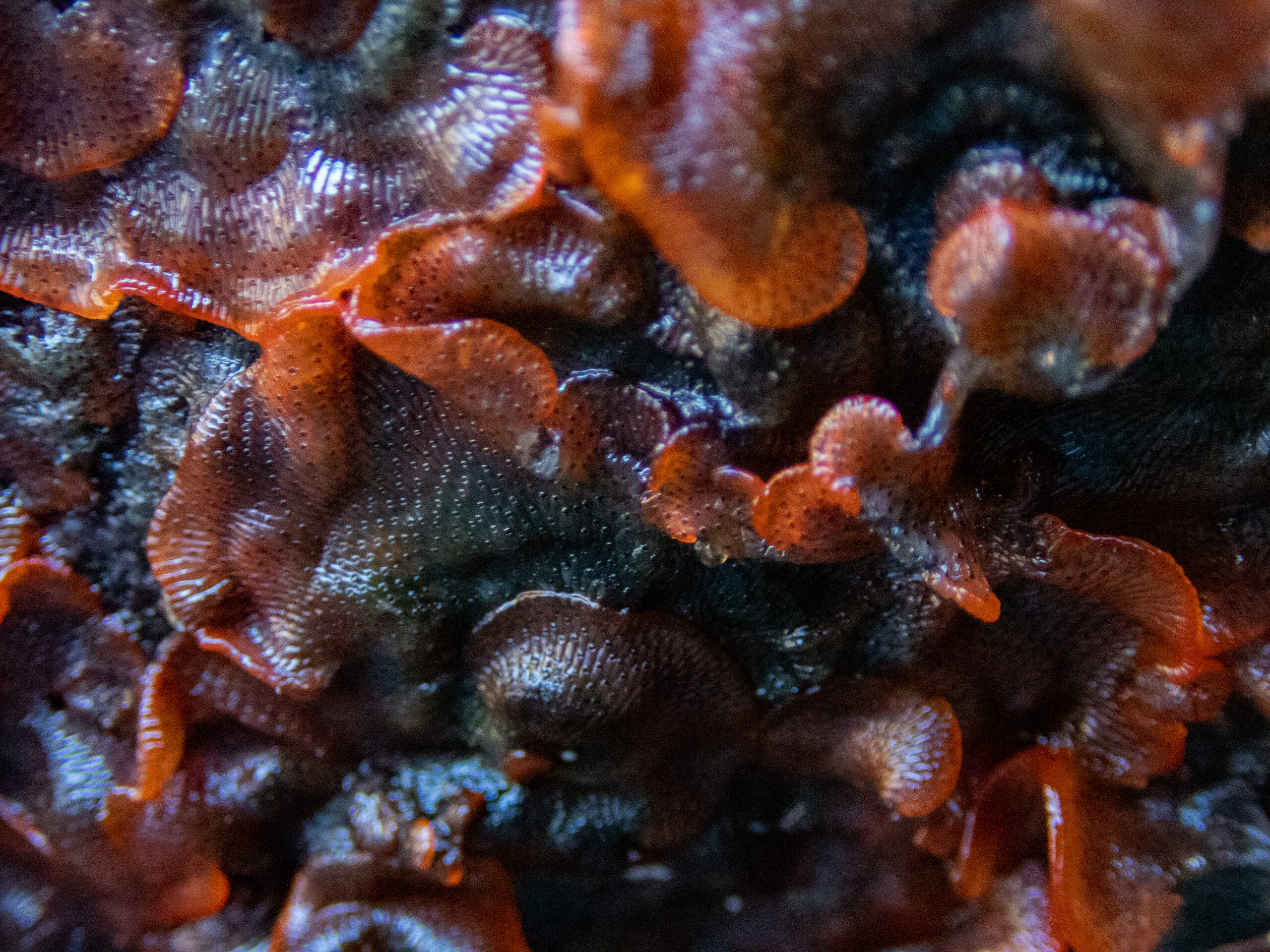

Some fungi fun: I haven’t had the time to research ID’s on most of these, so write me if you know and are keen to share?!

Vancouver Arm: Head of Bay, Third Cove, Stevens Cove, Breaksea/Te Puaitaha Sound – Fiordland.

Broughton Arm, Breaksea/Te Puaitaha Sound, Captivating! – Fiordland.

We were primed to love Broughton Arm. Tony, a New Zealand sailor we met in Tonga (from an Auckland sailboat building family) got there ahead of us and posted his impression, the humbling sense of privilege he felt to be in the remote presence of such mighty granite walls and peaks. “Paradise found!,” he exclaimed. It’s hard to think of a way to convey the heart sense of moving through pristine and unpeopled areas like this, the sense that goes beyond the imagery, the waterfalls, and magnificent trees, the wildlife. The sense of living stone and water and place. You look at one of the these peaks soaring above the the fiord continually stunned by the mass and energy represented there, and then by the bounty of life exuberantly, vividly greening those granite flanks. And water, water, water everywhere. ~MS

Wet Jacket Arm, not just any Arm – Fiordland.

Lots to captivate ~ lingering rainbows, new waterfalls, breathtaking bush, dolphins and surreal reflections while moving up to the end of Wet Jacket Arm. I wrote these words in the logbook from that day: ‘OH MY GOODNESS – A VISUAL FEAST!’

Delightful Dusky/Tamatea Sound – Fiordland

Dusky is the longest and most extensive fiord in Fiordland at nearly 24 miles in length. Named ‘Dusky’ after Captain Cook’s evening sail by in 1770, and ‘Tamatea’ after the renown Māori explorer who spent much time there. He’s also known for the coining the longest name of a place near Hawke’s Bay ‘Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu,’ so I’m glad I didn’t have to work that into our logbook! ~DS

Inner Luncheon Cove on Anchor Island, Dusky Sound

We are anchored in an 18th century naturalist’s illustration. The Kākā, subtly colored parrots, russet and carmine, gray and mossy green, chatter in mobs back and forth. Fur seals and their pups bawl and rumble along the densely wooded shore, draped on rocks, sunning just out of the vivid green tide, or hidden mysteriously in the forest. Rays and Broadnose Sevengill sharks patrol the shallows. Bellbirds chime and Wood Pigeons dive and soar in mating displays, wind whirring in their wings. The water is supernaturally still after the tumult and breaking swell of Broke Adrift Passage, and the long motor up the easing blue Pacific around Cape Providence. The scale of the world is abruptly more intimate. Captain Cook dined on crayfish here in 1773. He left behind a recipe for brewing beer from the bark of Rimu trees, molasses and yeast. The island is also predator free, and refuge to the rare ground parrot, the Kākāpō, once thought to be extinct – rediscovered in Port Pegasus, Stewart Island by Rodney Russ, a sailor/explorer we met in Christchurch.

A chance to sit on the bow and meditate outside, to the constant music of birds, “Here and now boys, here and now.”

The dearth of sandflies and still air made for a pleasant barbecue, cooking up fillets of the Albacore tuna we caught on our way into Dusky.

The trails on Anchor Island are named and well marked, though oddly, do not seem to clearly indicate which of the many paths lead to the lake (just a kilometer or two away). We weren’t very far along the “wrong” trail when a mob of Kaka settled noisly into the trees over our heads. We sat still and waited and they ventured closer and closer, sailing back and forth, gnawing at the branches with their strong beaks and then landed a few feet away, turning their heads upside down for a curious closer look. A South Island Robin/Kakaruai (re-introduced in 2002) also hopped over to say hello, as they do, finally summoning the courage to peck at the bottom of my shoe. ~MS

Fanny Cove, Dusky Sound

It was still when we arrived after the move from Anchor Island. Along the way we enjoyed the company of some of Dusky Sound’s residence Bottlenose dolphins, and stopped for a closer look at a waterfall, a hundred feet of depth under Allora’s keel a boat length or less from shore. We ate some bread that Diana pulled from the oven just as we entered the broad cove and thought about our plan for anchoring. The forecast was for twenty-five to thirty knots of northerly on the outside (a little less than the full Pusygar gale which prevails three hundred days out of a year), but all the models showed much less fifteen miles inland form the open sea. Still with the wind and williwas, we didn’t really know what we might get. The dramatic cove with the huge granite wall of Perpendicular Peak at the head is much bigger than in looks on the chart. The opposite of intimate Luncheon cove. We dropped in 60 feet of water and laid out all of our 100 meters of chain at a shallow angle along the shoreline, still sitting in thirty feet of water but with rocky shallows close by. Our first line would not really hold us off, and we ran a second as the wind came up and it was clear that the topography of cove seemed to twist the north wind with just a hint of west in it to solid west, coming at Allora from the port side and pushing us toward shore. The cove is big enough for a reasonable bit of fetch too, but the water on the east side is just too deep. Already worn out from setting the first two lines we debated putting out a second anchor from our midships cleat, but we worried about dealing with picking it back up if things got rough and we hand to move. We finally settled on putting out a third shore line using forty feet of chain to tie around a rock and pulled that up tight. By then the wind was pushing us with gusts of 18 knots. It went against every sailor instinct to be holding off a lee shore this way, but as long as our lines held it would take some mighty force indeed to drag 100 meters of chain and an anchor uphill. A power boat came in, and poked around on the east side and dropped anchor along the east side which we thought was too deep and we briefly wondered if we’d read the situation wrong (having no advice in our books about where to anchor in this broad open cove). But then they sent a dinghy over and we recognized the driver as he approached. Junate! from Hokey Pokey, a catamaran we knew from Papeete and the Gambier! We shared a brief excited catch-up about the last three years before he headed back. They’d also decided that it was too deep to anchor on the more protected east side and were zooming off (as only a power boat may) to find a mooring in another cove, much too far away for us to make before dark. And we were left alone with the wind, checking our shorelines and worrying how much more the night would bring. Just before dark the wind gusted to the mid twenties and Allora settled back about fifteen feet closer to shore than she had been. Our starboard shoreline went momentarily slack and the depth rose to twenty five feet. It began to rain. We donned foulies and went on deck ready to take more drastic action if it turned out that our anchor was actually not holding. We tightened up the breast line chained to the rock to pull us out into deeper water, and checked the GPS. We finally decided that the low tide had allowed some slack in our chain which the gusts shook out and we were holding fine. We made sure the dishes were away and everything was ship shape for the night, just in case, and then the wind quit completely, the rain settled in gently. In the middle of the night we woke up to an amazing stillness, just the finest pitter patter of rain. Light from a still nearly full moon softly lit the stunning granite faces that guard the entrance to the cove and the fine rain softened their reflection in the still water. It felt like a big reassuring landscape hug for a wonderful, still, uneventful night of sleep. ~MS

Seaforth River, Dusky Sound

It took us three tries to get the anchor to hold in Shark Cove. Communication from bow (Diana) to the helm (Marcus) is always a bit challenging (West Marine sells headsets called “marriage savers”). The view is different, too. We did alright for the first couple of attempted sets, but both got a little impatient and grumpy by the third. It held, and we were finally tied up, but tired and neither of us feeling great about how the teamwork had held up. There’s a lot at stake — sudden weather switches, unpredictable williwaws make it crucial to get this right. Every couple of days we get another chance to see if we can improve on our mutual desire to work together.

We got a little of a late start for the longish dinghy ride over to Supper Cove where the Seaforth River enters the Sound. It’s reported to hold brown trout! The Dusky trail slopes along the banks, through mud puddles and a podocarp forest of magnificent rimu, kahikatea, miro, mataī and tōtara trees. The river tumbles off some boulders and then flattens like a lake for several kilometers. Tea stained with tannins, spotting fish (the only way to fish in New Zealand) was tough. Ultimately we didn’t see any, though a few rocks got some very intense attention.~MS  We took Namo over to the next bay, Supper Cove, to be able to hike on the Dusky Track. It’s an advanced tramper track – 84km one way, but we just did 6km and found it muddy but heavenly (not bushwhacking).

We took Namo over to the next bay, Supper Cove, to be able to hike on the Dusky Track. It’s an advanced tramper track – 84km one way, but we just did 6km and found it muddy but heavenly (not bushwhacking).

While Wet Jacket Arm and Breaksea Sound are still part of the Dusky/Tamatea Complex, I’ve broken them up, if for no other reason than my own sanity, so I can feel a sense of progression, ha! ~DS

Minerva North, Haven in the Pacific

Of all the places Allora has taken us, North Minerva Reef, is a stand out. The reef literally emerges only 90cm at low tide, and when walking on what feels like the Pacific’s very precipice, we had the surreal sensation that we’d been transported to another world. I urge you to read this article from New Zealand Geographic, which lays out the inherent hazards and contentious history of this fascinating ‘land:’

We, like many others, made a stop at Minerva North, to break up the often difficult passage between Tonga and New Zealand. Most boats poise themselves to try to stop, but the weather conditions have to be right to enter the pass and take the time in ‘pause’ mode as opposed to continuing onward, so we felt lucky to manage 3 days in the fold of the protected lagoon. We weren’t alone, though! The 30 boats at anchor around us were dubbed, ‘The Minerva Yacht Club!’

Suwarrow, A Nature Reserve

Our stop in Suwarrow was comprised mostly of hiding from 30 knots winds created by a squash zone from a gigantic 1044 high in the south with effects that had people digging in from the Gambier to Tonga. So we don’t have much to offer about what you might do there to enjoy yourself. What we found out was more what you can’t do, and after French Polynesia and the Tuamotos the list felt onerous. Here’s what the ranger who was running things in the winter of 2019 said:

No anchoring except at anchorage island by the ranger station. Period.

No diving. Period. (Why?)

No fishing inside the lagoon.

No going ashore on ANY motu in the park anywhere except the ranger island (supposedly because of their rat eradication program)

Technically the rules even dictate when you can leave through the pass (not before noon) though I have no idea how they think they would enforce that.

There are more no no’s, mainly things you’d expect to be prohibited. At the bottom of the list, there’s a caveat that says the ranger can add anything he wants to the list, and the current Ranger took that to heart.

That leaves snorkeling, pretty much, and nothing else.

Unfortunately, though this obviously feels excessive and extreme, the behavior of some yacht visitors has served to make the ranger feel more adamant about enforcing and expanding his rules. It doesn’t help that some people feel they have a right to harvest coconut crabs and even lament not having taken more when they found out they could sell them for big money in Niue. Or that some members of the ARC (Atlantic Rally for Cruisers) showed up before the legal opening, trashed the place (according to the ranger) and left their flag planted on the beach. Suwarrow is a designated sanctuary and should be treated with the same respect as a national park anywhere.

Because the forecast called for the possibility of SE winds over 50 knots we asked for permission to anchor in the better protected SE corner and were denied. Unwilling to test the ranger’s theory that the allowed anchorage would be safe (there is at least one yacht sunk on the NW corner of that tight anchorage with south exposure), we moved, despite his objections to the south east corner, invoking our right under international law to ‘safe haven.’ Our biggest concern was the 3 mile fetch that the allowed anchorage would be exposed to. The anchoring was very poor in the SE, with coral and bommies everywhere, but it was definitely a safer spot. If we did drag we had miles to react rather than the tight lee shore of the approved anchorage. This decision did not make us popular with the head ranger, but we felt we had no choice for the safety of our boats. In the end I don’t think we saw over 35 knots, but I personally would make the same decision again.

We left as soon as it was over.

~MS

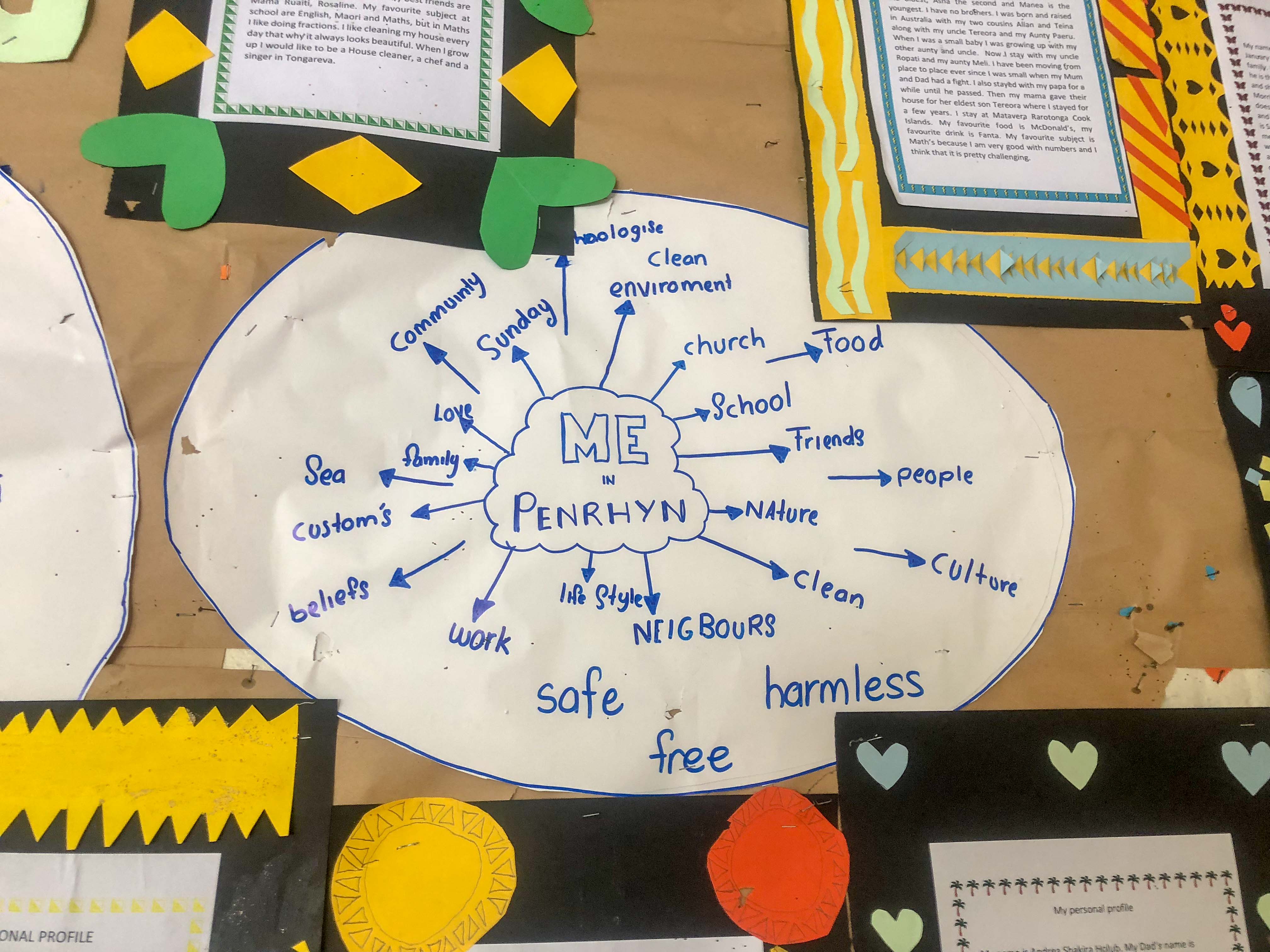

9° south of the equator

“It’s hot here,” the Pastor’s lovely wife said with a smile, “it’s always hot. Sometimes you can see some flowers blooming and you know it’s Spring, but it’s always hot.” The village of TeTautua does not own enough cars to have much of a road so its houses tend to meander along foot trails, which double as scooter and motorcycle paths, a web centered on the imposing blue and white Cook Island church. Ungirded by streets, houses with deep porches, windows without glass, only tattered cloth curtains, lay scattered at random angles. You might forget to notice that there are no dogs (they have been disallowed by the island council, which makes everything its business). Their absence, as much as the haphazard city planning, creates the feeling of a ghost town, especially if the children are in school and the hot sun is broiling the gray coral gravel underfoot.

The island is losing its population, slowly, people emigrating to bigger more populous islands, or New Zealand. Though there is an abundance of fish, there are few (maybe none) of the occupations that keep idle hands busy in even the smallest midwestern ghost town. In the big village on the other side of the atoll there is a nurse. There is a policeman, somewhere. There are teachers. But there are no stores. There are scant few gardens, a difficult enterprise in the hard limestone pavement that constitutes the earth of an atoll. There are thriving coconut groves, possibly the remnant of a copra operation, the kind that is still subsidized in French Polynesia. For a while there was a booming pearl farm business, which succumbed to cyclones and a disease among the oysters. Perhaps the mental, emotional, spiritual space that in North American suburbia is filled with cars and traffic lights, malls, donut shops, Home Depot and Costco, here is filled by the sea herself and the Cook Island Christian Church.

It’s no secret that missionaries did a number on the South Pacific. This is still one of the main places those white shirt and tie young scrubs in the Salt Lake airport are all headed. But it was news to me that God apparently doesn’t want you to fish on Sundays (I thought Jesus was a fisherman). No work, no play, no music, no swimming (sound familiar?). Like a friendly, island version of the Taliban, they take these injunctions seriously in Penrhyn and they made it their business to see that we anchored right by town to ensure that we weren’t off enjoying ourselves on Sundays doing the devil’s worst out of sight of the church’s two story pulpit.

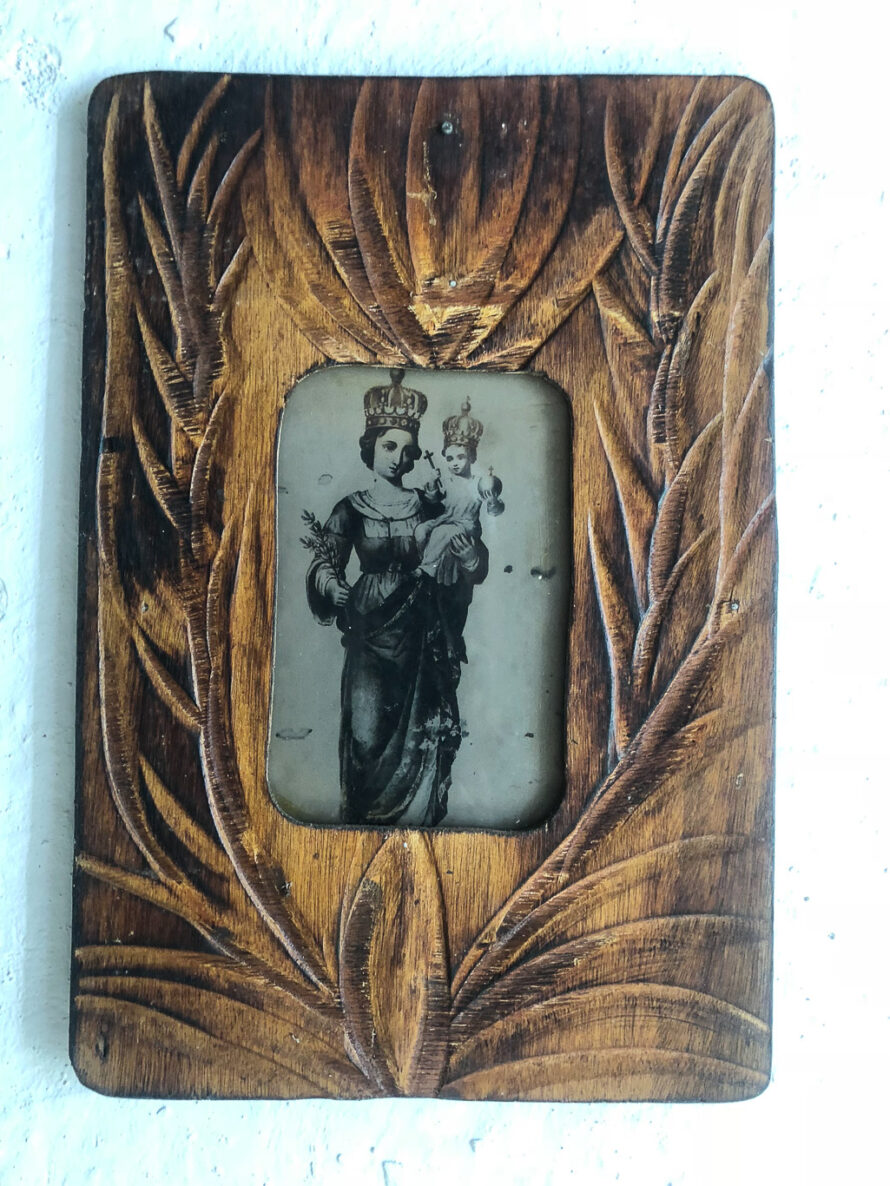

Naturally, we were invited to church. Hats strictly required for women (strictly not allowed in Tonga) but definitely NOT permitted for men. Diana showed up with a beautiful head wreath from Rapa (made for church there) but here she was told she had to have a hat that covered the top part of her head (cuz God is looking down, I guess?). Long pants for men (in the tropics!), luckily Mike had a light pair I could borrow so I didn’t have to wear jeans. The Pastor’s white pants (God only knows how he kept them white) were unhemmed and about eight inches too long for him, so he walked on them, barefoot when he greeted us at his house and then under sandals for the service. He carried a bible, well worn with pieces of folded paper tucked among its pages, King James translated to Māori/Tongarevan, the language of the Cook Islands.

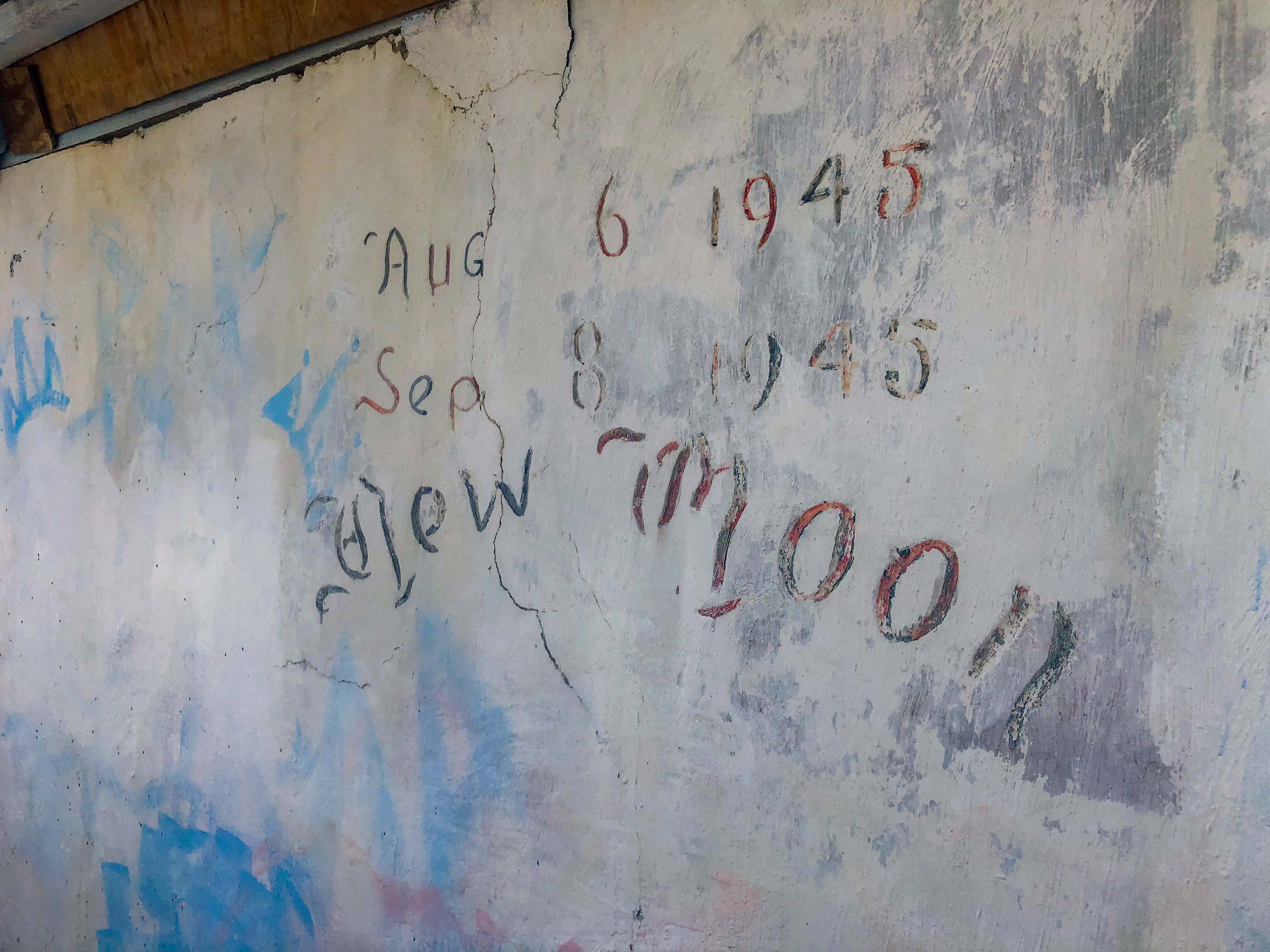

We arrived in the morning to find out that regular church had been cancelled because an elder woman, Mama Takulani, mother of 12, had died in her sleep early that morning. She had lived on Penrhyn her whole life, in this village of about fifty people, with barely one dirt road and about four cars to drive on it, no stores, no post office, nothing but a collection of very simple homes occupied by people who must know each other very, very well.

We gathered at her house, the palangi (foreigners) outside on plastic chairs to witness a three hour funeral, mostly singing, which seemed unscripted and improvised, arising spontaneously from the group of women seated on the patio floor. Men joined in, and the harmonies were unlike anything we’d ever heard, oddly discordant and complex, a fascinating mix of church hymns and Polynesian music, all the more intense as an expression of mourning. Speeches were given by men, long speeches, in the local language, with occasional acknowledgements in English to the visiting Palangi. The woman’s body was carried to the church, in through the left-hand door, briefly spoken over, then exited through the right-hand door. She was buried in a pre-built concrete crypt in a hole dug that morning by a backhoe outside her bedroom. She was covered with a tapestry and laid in the ground. It felt very odd to witness something so profoundly personal and significant for our hosts, though they went out of their way to make us feel welcome, and afterward there was a feast, with an insistence that visitors eat first.

The next Sunday (Father’s day!) respecting their local commandments and traditions, I did not fish. The first time that has happened since I became a father, 27 years ago. Instead, we went again to church to be harangued, mostly in Tongarevan, but also in English, by a series of men who (like the pastors of Rapa), utilized a hierarchically arranged pulpit (literally with stairs) to wield their authority. Maybe you need something organized like this on an island with nothing but turquoise water and sun and fish, to keep people from running amok, though it felt so out of place with the usual island vibe of very friendly, relaxed, open people. Singing provided some relief in the service, though the performance was more structured and a little more hymn-like than what we witnessed at the funeral. There’s a lot of this kind of singing in Penrhyn, all through the week, several times a day on Sunday. They grow up with this music, so they sing with passion and confidence and subtlety. The women often hold a hand to their face as they sing, and I wasn’t sure if it was to help them hear their voices (the way you might imagine Sting in a recording studio), or to hide their faces and wide open mouths. One young woman held a book that blocked most of her face. Afterward, there was another generous feast at the Pastor’s house, with pictures of the gathering of foreign visitors (representing several countries in Europe and North America) to be posted on Facebook.

When it seemed we would be on the island for another Sunday (waiting for a weather window to depart, and fishing) we decided we would skip church, but thought we’d better say something about our decision in advance. The Pastor seemed relieved (the unexpectedly large group of sailors must have been hard on his freezer, which would not be refilled until the next supply ship, months out). He did admonish us not to do anything on our boats, especially not swim, and seemed to joke (not sure here) that the sharks were in league with God and would enforce the no swimming on Sunday rule. Diana spent about five hours in the water cleaning our hull anyway, and lived to tell.

Though we chaffed at being required to observe the religious regulations of the island, presented to us as Law (which almost certainly cannot have been constitutional in a country governed by New Zealand) we were also overwhelmed by the generosity of their reception. Gift giving and hospitality is a pervasive and vibrant cultural practice throughout Polynesia, and they outdid themselves. We did our best to give back, too. And although the dogmatic Christianity was a tad stifling, we still managed to have some good connections. The Pastor was a bit of an odd duck in that way, at least for me, it was very hard to engage him in a regular conversation. His relationship to the visiting foreigners seemed mostly about the opportunity to give speeches and express the piety of his flock and the importance of his position as their spokesman.

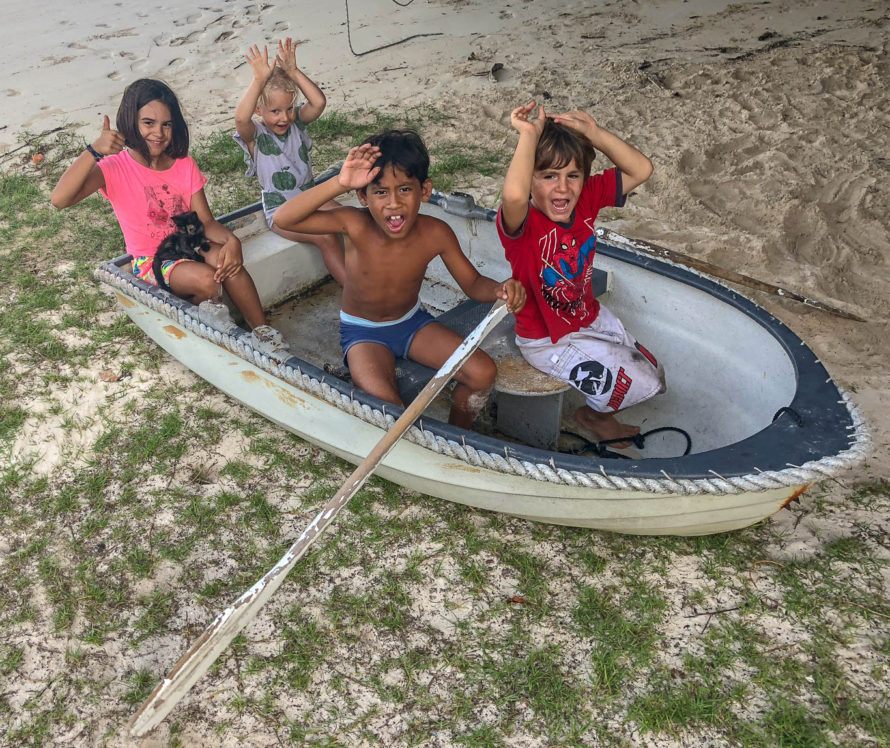

We were the fourth boat to visit Penrhyn in 2019, but within two days there were eight more boats. Most of them part of a group of kid boats (that is, boats which have kids on them, who generally drive the social schedule), all loaded with school supplies to give to the children of Penrhyn. Liza, of the boat Liza Lu, is a teacher from New York whose class had started a pen pal relationship with Penryhn before coming. She had more postcards to deliver and spent time at the school helping the kids compose new post cards that she would mail back to her school. Our friends on Alondra, marine biologists with two girls, eleven and twelve, brought in microscopes and spent a day with the students peering at everything from fly eyes to butterfly wings and gecko toes. A huge hit. The boat ‘Panacea’ with Tuomo, Reka and their kids presented a slideshow about how they’d come to be there aboard a sailboat, and shared glimpses of all the countries they’d seen. The families aboard s/v’s Luminesce, Calle II, Itchy Foot and Caramba all participated, too, and Adagio’s crew were elemental helping with the mosaic. It was an unusually bustling ‘point in time’ on the sleepy eastern side of Penrhyn … ~MS

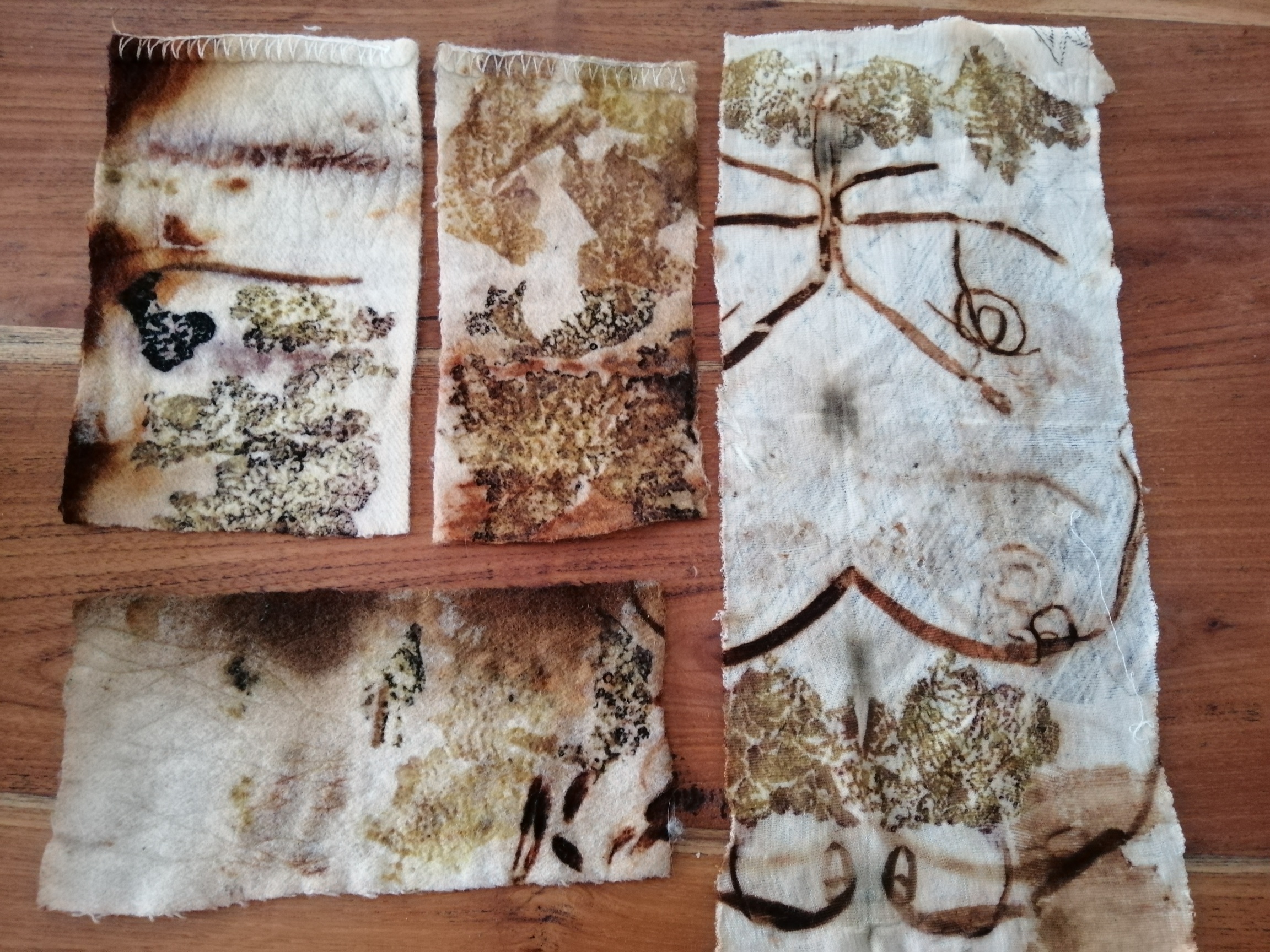

Lots of love in this mosaic!

Diana spent a day at the school (and several more on the boat) helping them make a mosaic for the school using local materials but also glass from Italy that she keeps squirreled away in the bilges. She donated for a center element, a piece of glass given to her by a mentor in Ravenna. The theme for the month at school was “Love,” so that inspired the design, which was set up so that many kids could work on parts of it at once. Thanks too, to Mike and Katie (s/v Adagio) for jumping in to help. We hung it on the school wall with the assumption that it might outlive the actual building itself. ~MS

The Bird Motus of Penrhyn, Cook Islands

Stevens/Stevens Rendezvous Society Islands

In May we had the chance to buddy boat with my brother Doug and his family and friends. They flew from Washington and chartered a catamaran big enough to accommodate eleven people on board. We kept a pretty busy schedule touring Raiatea and Bora Bora, hiking, snorkeling, sailing, diving, SUPing and kayaking. A few of us fit in an epic, muddy climb to the top of the peak of Bora Bora. It was great fun to sail alongside my brother, beat him sailing to windward and then watch him blow by us like a ghost ship with the wind behind the beam. He hailed us on the VHF sailing to Bora to tell us that for the comfort of his crew and to keep up with us on the windward leg he was turning on the engine. I said, “That’s awesome (I never expected to be able to beat that catamaran) he said, “Great for you, Marcus…” Evenings onboard Kiwi will probably stick with us the longest. I guess sunsets are like that. After a long day of whatever and wherevering (usually in the water) their ridiculously spacious Bali 46 was a great place to hang out with no particular agenda, sip a little rum or scotch, a glass of wine or a dark and stormy and enjoy the warm tropical breeze and another delicious meal. ~MS

Sweet Tuamotus, Last round through …

I’m going to ask Marcus to wax poetic about our final weeks in the Tuamotus. Suffice it to say that this region of French Polynesia is most definitely a favorite of ours and I even heard Marcus say he could live there. If fresh produce was available, I might be on board! For the time being, these pics can be a placeholder. These are shots from Tahanea, Fakarava and Rangiroa.

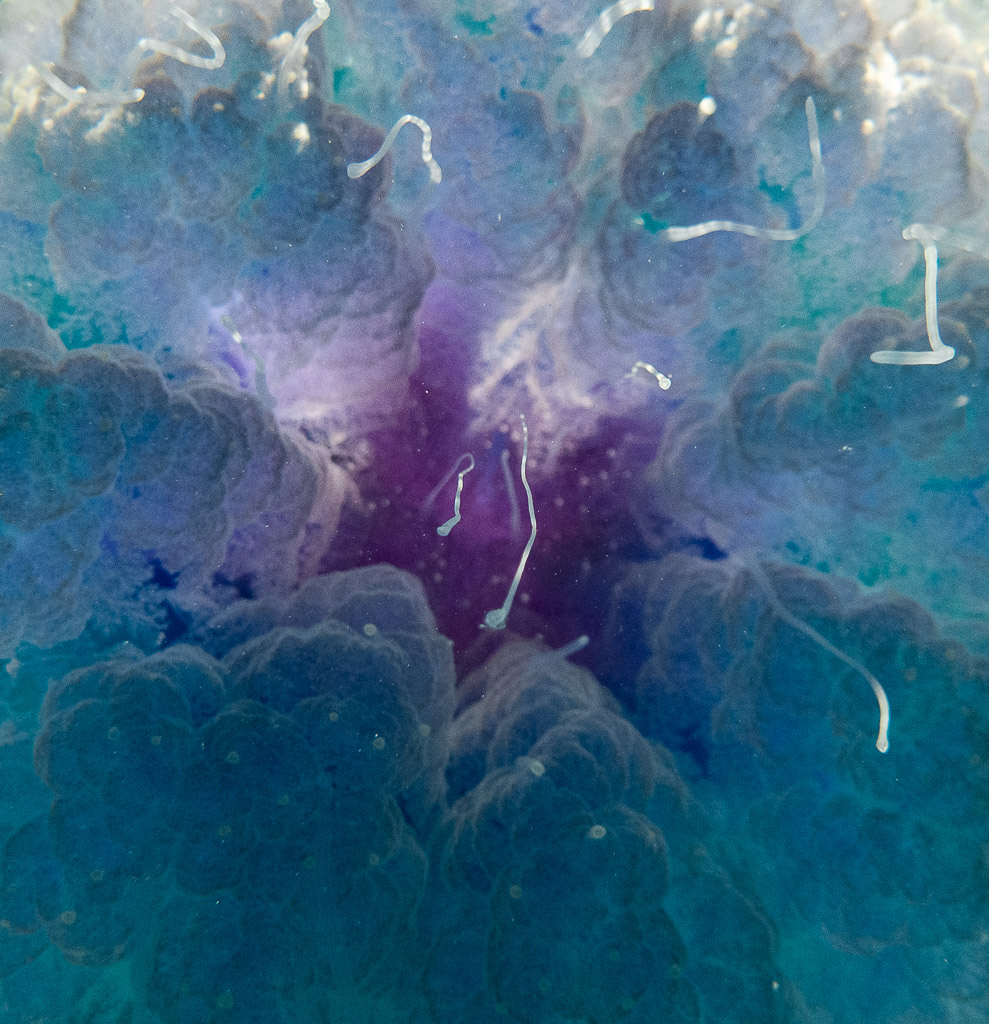

Cephea cephea/Crown Jellyfish

Tahanea, Tuamotus – April, 2019

We saw these dinner plate sized jellyfish while meandering around the SE corner of the lagoon searching for our anchorage. I hoped they’d stick around so I could get a closer look, because I could see that they were intriguing, but I HAD NO IDEA!! These shots were taken over 4 days of 15 -20 individuals. I was mesmerized!!! We were without wifi, so couldn’t even learn about the magic I was witnessing, but I was aware of being incredibly lucky to live on a planet where such a creature exists.

A quick search reveals a paucity of information about this jellyfish, but here’s a bit of what I found: Cephea is a genus of true jellyfish in the family Cepheidae. They are found in the Indo-Pacific and East Atlantic. They are sometimes called the crown jellyfish, but this can cause confusion with the closely related genus Netrostoma or the distantly related species in the order Coronatae. They are also sometimes called the cauliflower jellyfish because of the cauliflower looking crown on top of the bell.

Common Names: Crown Jellyfish, Cauliflower Jellyfish, Sea Jellies, True Jellyfish, Transparent Crown Jellyfish and Crown Sea Jelly

Scientific Name: Cephea cephea

Elizabeth and Michelle, Mom/Sis team 2, Gambier!

cerulean seas

rain storm snorkel,

diving (with and without weight belt),

sharks, shells, sand, sailing in the lagoon

bugs on the beach, turtles

coconuts and an ancient village

Taravai petanque, ukulele and guitar

gusts from the mountain

anchoring pandemonium,

slow time and quick time

Valerie’s painting with sand

more fish more music

more fish more fish

damsels, butterflies, leatherbacks, grouper

parrot fish, sling jaw, guinea fowl puffer

canyons of coral, warm water

singing, laughing, lazy days

~MS

Mom and Lori team up in the Gambier!

Our 2019 ‘cyclone season’ in the Gambier kicked off with visits from our Mom’s and sisters. Mom and Lori arrived at the end of January and we enjoyed a couple of weeks aboard Allora, sharing our favorites (people and places) in this sweet eastern corner of French Polynesia.

Mom certainly knows her way around the boat, so she slips into very relaxed mode and we always marvel at her being ‘game’ to do just about anything. This was Lori’s first full-fledged stay aboard, so it was particularly wonderful to immerse her in our life afloat. These were full, rich days!!! ~DS

Through Lori’s Lens:

Through Wyatt’s Lens, Gambier, 2019

First Round: Gambier 2019, with Wyatt and Maddi

DIVE IN! We’ve been to the Gambier before, this little Archipelago on the southeastern edge of French Polynesia, clinging to the tropics by a few minutes of a degree. From any place to any other place in the Gambier it always seems to be six miles. Motus, reefs, mountain islands, all of French Polynesia on a small scale. Not a lot of people anywhere, basically one road on Magareva, no traffic lights, or stop signs or yield signs. No internet to speak of.

We’ve been to the Gambier before, this little Archipelago on the southeastern edge of French Polynesia, clinging to the tropics by a few minutes of a degree. From any place to any other place in the Gambier it always seems to be six miles. Motus, reefs, mountain islands, all of French Polynesia on a small scale. Not a lot of people anywhere, basically one road on Magareva, no traffic lights, or stop signs or yield signs. No internet to speak of.

The business of the Gambier is pearls. Its cooler water temps and open lagoon are ideal for cultivating that one particular oyster which has captured the imagination of the world’s great connoisseur and collector ape, an irredeemable species with a bizarre obsession with grading things according to their level of perfection, and assigning abstract value. Toiling like 49’ers, cleaning the oysters, nurturing and counting them, performing delicate surgeries to create little iridescent balls of nacre.

We had lots of company in the Gambier this time around. Lots of time to go explore some of the places we missed the last. We thought it would feel like lots of time in general, but I guess Time doesn’t exactly work that way. First to arrive was Maddi, followed a few days later by Wyatt’s girlfriend, Heather. All passionate outdoors people, crazy about running over mountains and diving with sharks and mantas. Heather kept a diary of the fish she identified (as a scientifically trained person would). She and Wyatt would pour over Diana’s books at the end of their dives. Diana’s pretty good at this, but I’ve been slower remembering the names of (non-game) fish. One that Wyatt and Heather found that has stuck and is easy for me now is the Piano Fangblenny. Nice name for a fish with what sounds like a mean habit of eating other fishes scales. We had lots of music and card games for the rainy days. Maddi hooked a giant bonefish right off the shore in front of Eric’s. It charged her fly and then ripped into her backing. She landed the next one. Wyatt landed a nice fish there, too, a few before having eluded getting their picture taken by slipping off the hook at the very last second. We dove, exploring new places in the Gambier, had some gear trouble, and then got that fixed. We played volleyball in Taravai and climbed Mt Duff in the pouring rain. It felt quick (as almost everything seems to these days) but filled with memories.

The weather was unsettled during most our stay this year in the Gambier. Everyone says so. It’s a thing. We had great weather and we had rainy weather. We had calms that made it possible to swim with mantas at Ile Kamaka and spend a wonderful Sunday afternoon relaxing in the shallow water beach in front of Eric’s pearl farm. We also had the worse wind we have ever experienced at anchor, a glancing blow from a depression that plunged the barometer to the low 990’s. Top gusts of 54 knots and sustained winds of 40 knots. A proper gale. Other sailors certainly got tired of us commenting that it wasn’t like this last year.

The weather was unsettled during most our stay this year in the Gambier. Everyone says so. It’s a thing. We had great weather and we had rainy weather. We had calms that made it possible to swim with mantas at Ile Kamaka and spend a wonderful Sunday afternoon relaxing in the shallow water beach in front of Eric’s pearl farm. We also had the worse wind we have ever experienced at anchor, a glancing blow from a depression that plunged the barometer to the low 990’s. Top gusts of 54 knots and sustained winds of 40 knots. A proper gale. Other sailors certainly got tired of us commenting that it wasn’t like this last year.