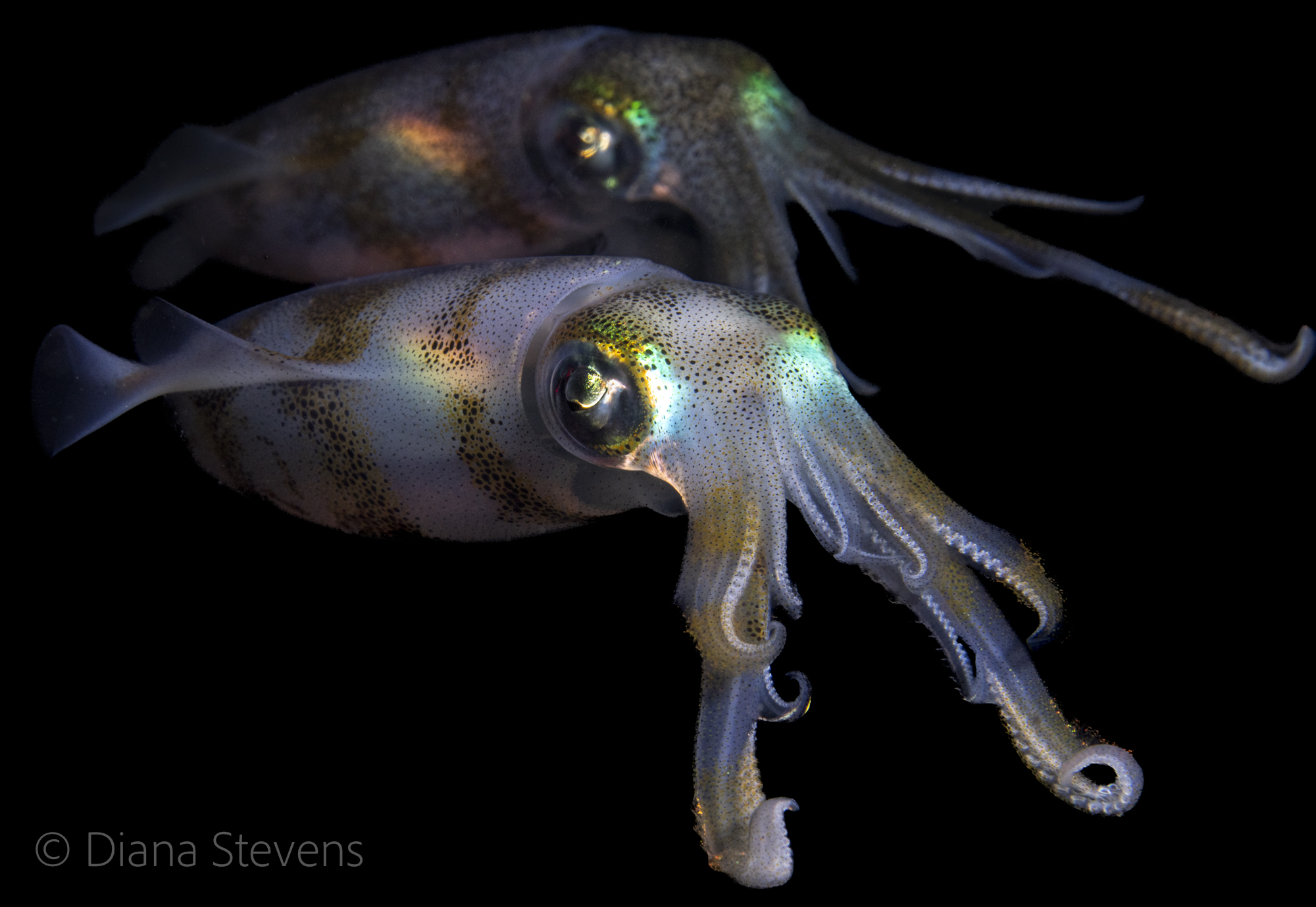

The final Lembeh Strait muck diving album (see the previous two posts for more crazy creatures from these murky waters).

Tag: Meditation

Run A MUCK – Lembeh Strait #2

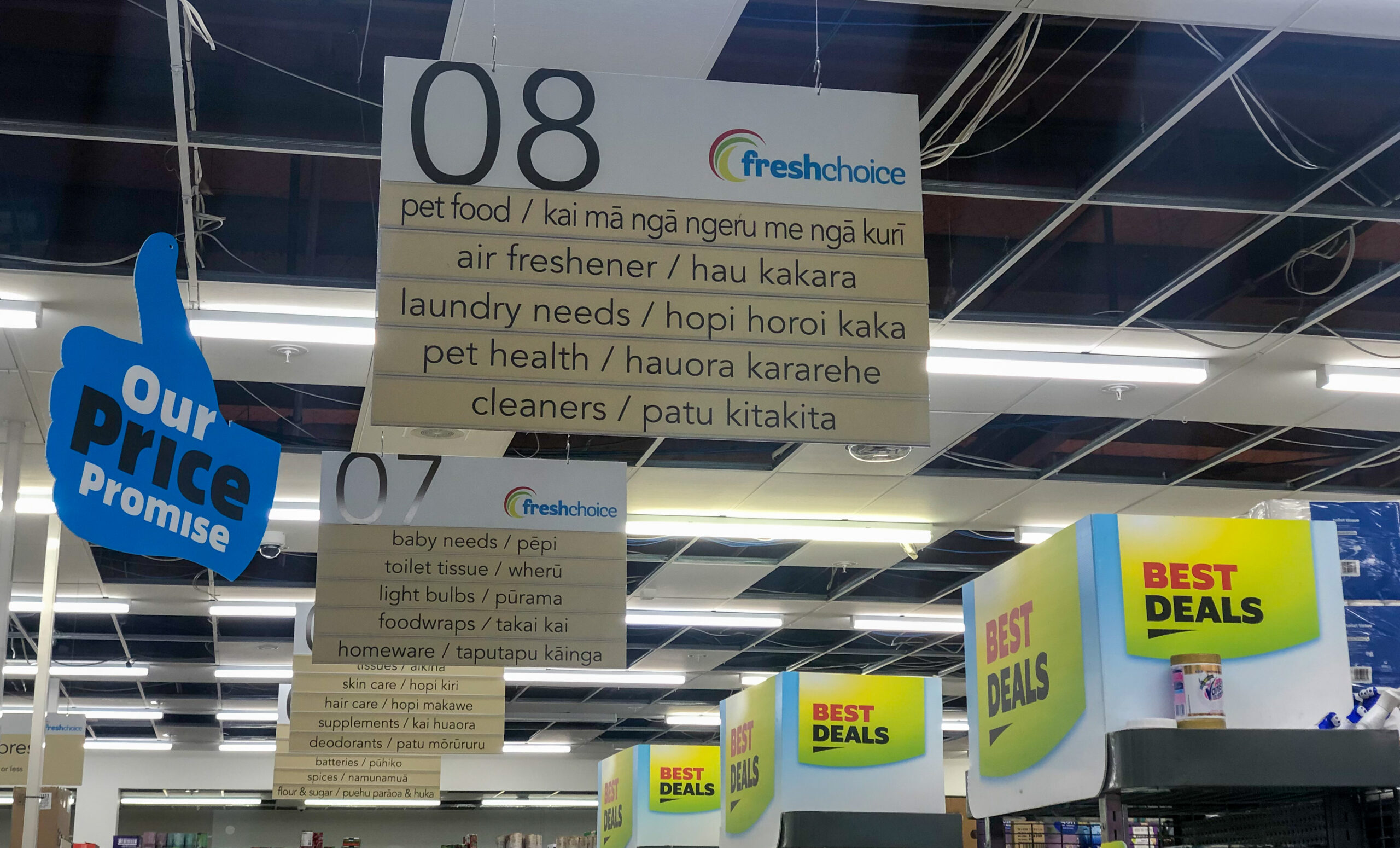

Arohanui South Island! Passagemaking Northward.

Picton to Opua via Napier and the East Cape (duh, duh, duh)

Diana’s last log entry on the first leg of this passage: “worst passage ever.” Maybe, I’m not sure, but I confess to getting seasick, for only the third time ever. Even so, I think the hardest part was leaving the South Island in dead calm with the threat of drizzle. After two and half years, it felt like leaving home, not least because we were leaving Haley and Liam, and knew it would be a while before we could get back.

Fueling up, (which for some reason is always a little stressful for me), was extra stressful knowing it was the last thing to do before saying goodbye. After multiple hugs and lots of tears, there was nothing to do but cast off the lines and pull away.

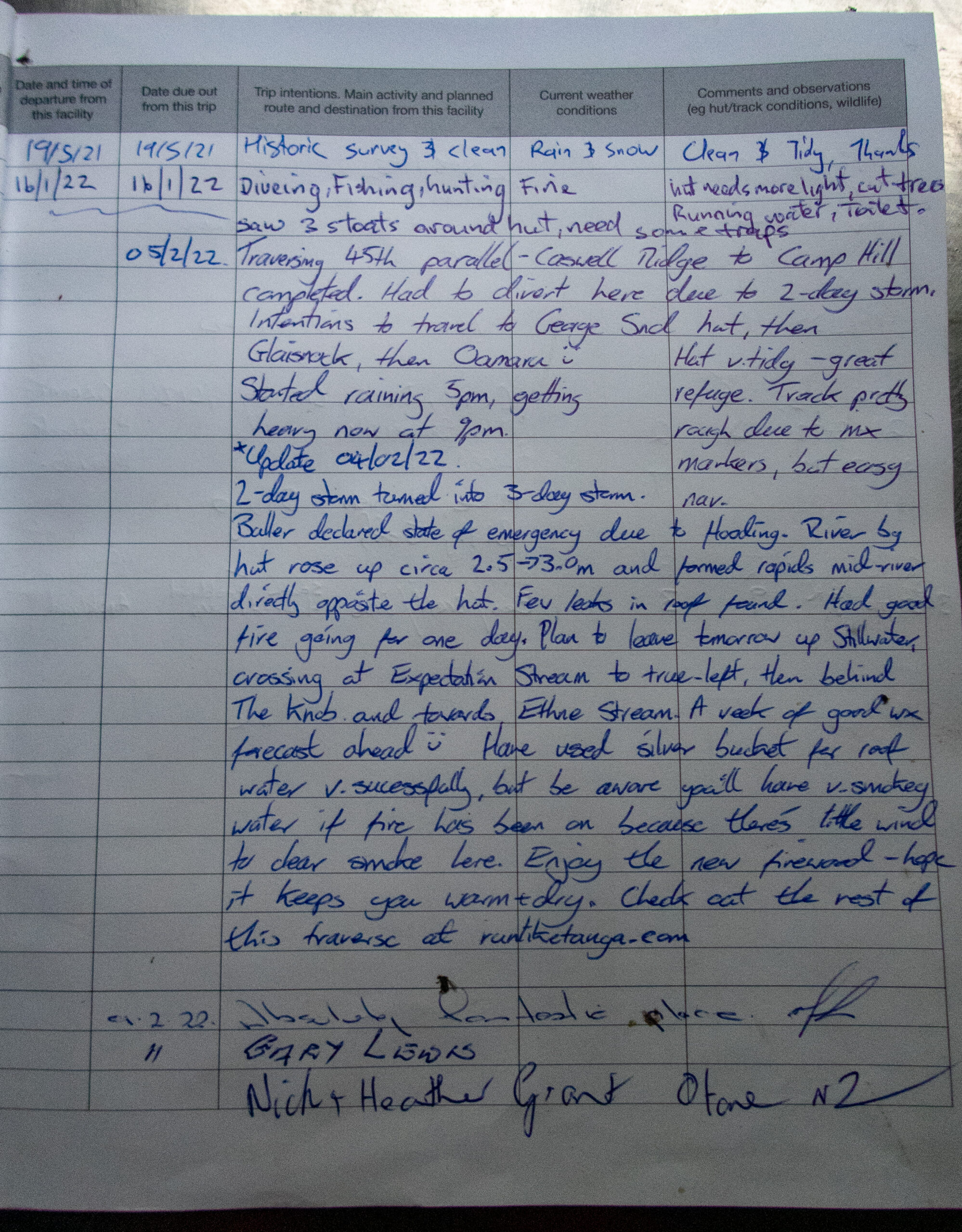

We were on a bit of schedule, running out of time to get to Opua before Maddi arrived from the States. Also, it was crucial to time our exit from the Tory Channel for a reasonably favorable current, the basic recommendation was leave on high tide out of Picton. We led that by an hour or two to try to avoid encountering head winds in Cook Strait. It was pretty mild to start and Diana made some super yummy wraps for lunch (she is the undisputed Empress of wraps in my book). As seems to so often be the case sailing around New Zealand, there was no chance of entirely missing the wind shift, and about halfway across we were sailing close-hauled. At least the seas, at that point weren’t too bad, not stacking up against current or anything. I went down to take a nap, and missed Diana logging 13 knots surfing on seas that were getting pretty steep. In fact, we wandered into the edge of an area of rip tides and overfalls, ‘Korori Rip,’ that was pretty dramatic. As it got dark the wind was on our beam and so were the steep seas. Diana was feeling pretty awful, and then I got sick too. This might have been where Diana logged “worst watch ever,” – she was really feeling bad and then the rudder on the hydrovane (our wind vane steering system) came off and started pounding on the stern. It took Diana a couple minutes to figure out what was going on, what the loud noise was. I donned a PFD, clipped the harness in and took a knife out onto the swimstep, hoping that I could cut the safety line off without losing it. It was pretty wet, but I didn’t want to take time to put on boots, so I opted for bare feet. Anyway, it actually wasn’t that bad, Diana has set up holder for a good sharp dive knife and a pair of pliers under the lid of the lazarette where they are super handy (she’s pretty good at coming up with that kinda stuff). I took the next watch and Diana tried to sleep off her seasickness. Once we cleared Cape Palliser things improved dramatically.

No doubt timing arrivals, departures, capes and channel entrances can be the trickiest part of sailing. You’re always trading one ideal for another. The next challenge of this passage was the East Cape, which is massive and takes a couple days to fully round. The forecast was for 4 meter seas and forty knot gusts… not super inviting. We liked better the sound of a snug marina slip at Napier to wait for the weather to ease up a bit, but that meant arriving at midnight, which is something we are loathe to do if we’re not really familiar with the layout. It’s never nice to feel like your options are bad or worse. As it turned out, the wind in the harbor was still and the passage in, though shallow, was well marked and very well lit. We glided to the visitor’s berth next to the travel-lift, easy peasy. The quiet and calm felt glorious.

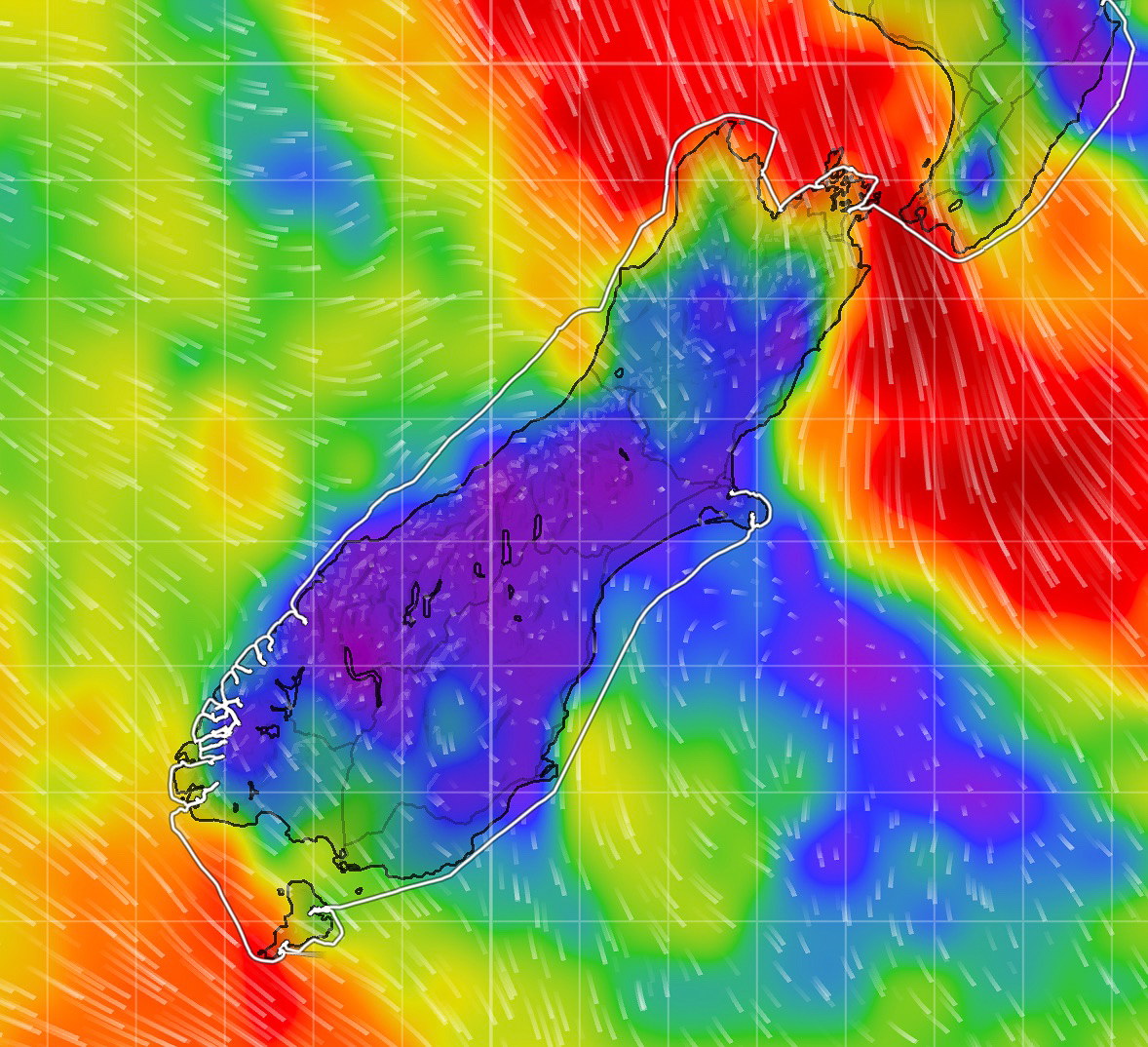

Waiting for the gale at the East Cape to ease came with a trade off — the near certainty that we would have to pass through a frontal system to reach Cape Brett. Yeah, I know, a lot of fretting about capes, but there’s a reason so many of them are given awful names by sailors (Cape Fear, Cape Runaway, Punto Malo, Cape Foulwind), they really do run the show. In the meantime, that lay two days in the future. We rounded the East Cape in the early morning, jibed and then enjoyed a glorious daytime sail headed northwest, pretty as you please, even got the guitars out for a little music.

The squalls started with darkness (naturally). Note to self: frontal passages are not to be taken lightly! Also I’m going to try to remember that the forecasts don’t really represent true wind speeds in these conditions. These are more like what you get with squalls in the tropics (sudden doubling of wind speeds) but over a much more sustained area and time period. Soon we were double reefed on main and jib, taking big seas over the whole boat.

Once again, Diana took the hardest watch (you might accuse me of scheming here, but I swear this is just a matter of chance). Her words from the log: waves over bow, raucous, deluge, still dumping. Mine: rain, clearing, wind finally calming. At least I tried to make up for it giving her a longer watch off, putting in four hours to clear Cape Brett. All the while looking forward to the forecast easing and a swing of the wind for a quiet sail into the Bay of Islands. No such luck. Wind died, and then the engine died, 8X according to Diana’s notes. At 5AM I was back on, and eventually the mystery of the engine was solved. I was so focused on the last engine issue back in Fiordland (which was entirely electrical) that it took me a while to realize that the current problem was oil pressure. I’d checked the oil, but with a heeling boat, the reading was off. I added oil and the engine was happy again. More engineering-inclined-sailors than I have expressed skepticism about black boxes (computers) on marine diesel engines, but for the less mechanically minded (yours truly) they can actually be a life saver. Better the engine shut itself down than damage something, though it’d be kinda nice if the $1000 panel offered something a little more elucidating than “CHK ENG.”

Dawn came quietly, and it worried me a little to see fog along the coast, but it dissipated as we arrived, and pulled into a quiet slip in the Bay of Islands Marina. ~MS

“The Picton TIME Project”

For this blogpost Diana asked for some words about “the reality of time,” which seems rather an ambitious metaphysical topic for a blog about two people goofing off on their sailboat in beautiful places. But here goes.

Time? What time? As sailors “living the dream” obviously, we don’t ever have a “schedule.” We do whatever we like, whenever we like, for as long as we like. With a few caveats.

First there are a few not insignificant constraints imposed by Nature — forces in the natural world beyond our control (so all forces of nature), stuff like sea state, wind, cyclones, storms, calms, ocean currents, physical laws governing displacement hull speed, gravity (this is a big one), the sun (and the massively destructive force of UV), the evil spirit that inhabits machinery, salt (never to be underestimated), electrolysis, whatever it is exactly that makes rust, and also biological forces like the stuff that grows on Allora’s bottom no matter how much expensive, toxic paint we apply, and Covid 19.

Then there are a few, also not insignificant constraints imposed by Governments — most importantly border formalities, and arbitrary human designations of authority abstractly represented as nationalities.

Then there is the stuff absolutely everyone contends with, sailor or no, like the second law of thermodynamics and Space and Time, or spacetime, or whatever this stuff we all swim about in is properly called.

We calculated that we were two months worth of Time behind “schedule” for most of 2021 and well into 2022 when all of the above mentioned irresistible forces collided with the expiration of our New Zealand visitor’s visas (extended at least four times because of Covid) on June 30, 2022. (And also, Winter, that ominous and unpleasant climate event of the mid and high latitudes which seems to come up much more frequently than a reasonable, fun-loving sailor might like).

We had a mighty to-do list, and spent most of the months of May and June feeling fairly overwhelmed as we tried to play catch up.

As to the metaphysical question of Time, perhaps it is philosophically or scientifically possible to question its objective existence (not that those are arguments I could ever hope to follow), but when all these forces converge, time can definitely feel in short supply, cramped, and very real indeed. We tried to remind ourselves, during rare moments of pause, that time, whatever it is, doesn’t really contract or expand. There’s always just today and what’s happening right now. Right? All of this busy-ness is just so we can sit around and procrastinate later, and find ourselves once again, about two months of time behind. ~MS

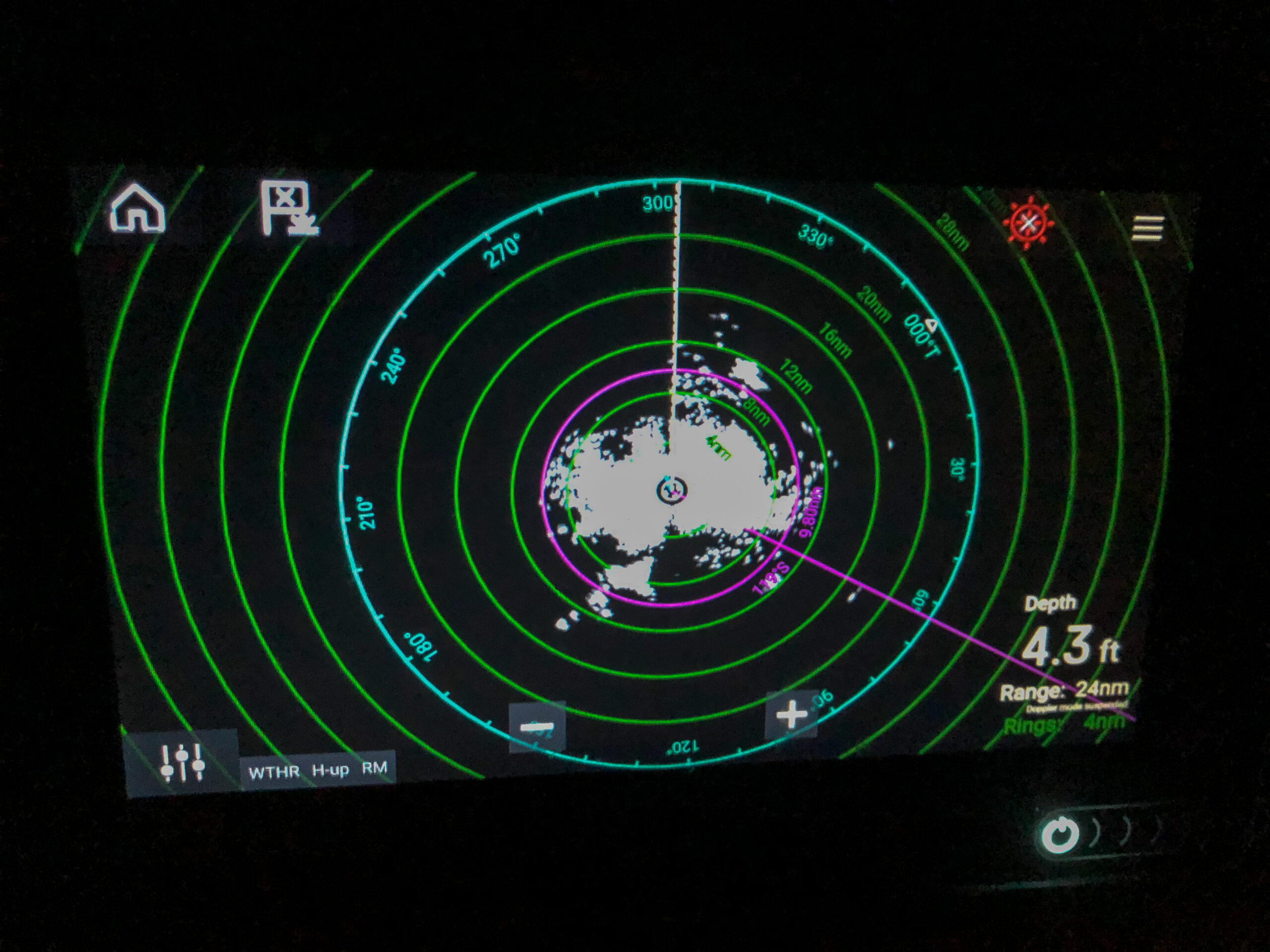

Passagemaking: Milford Sound to Abel Tasman National Park, South Island/NZ

It was a bit spooky sailing out of Milford at midnight without a moon. We had our inbound tracks on the chartplotter to follow, but it’s pretty amazing how disorienting darkness can be, even for feeling whether to turn to port or starboard to follow a line. Also with the steep granite walls, we didn’t feel 100% confident in our GPS. Diana went to the bow, and I stepped away from the helm to try to orient myself every few minutes, as we moved cautiously down the fiord. Though the GPS did seem to have a decent idea about where we were, it was also reassuring to have radar confirming the distance to the rock walls on either side. But what helped me relax most at the helm, was when Diana shouted that the dolphins had come to escort us out. I leaned over the rail and could just see and hear them splashing off our port headed for the bow. It was hard not to feel like they’d showed up intentionally to reassure us.

One of the many challenges of the passage from Milford up around Cape Farewell into the Cook Strait, is that there is only one place you might possibly stop, but that requires negotiating a river bar entrance at Westport (just north of Cape Foulwind!), which is safe only in decent weather. Otherwise, it’s a solid three day run (if you keep your speed up), which just barely fits into the cycle of weather shifting from South to North. The weather window that presented itself to us seemed pretty typical, catching the end of a southerly, motoring and motor-sailing through variable winds in a race to meet the Cape with relatively light winds rather than the usual NW or SE gale.Leaving sooner, we’d have had more wind to sail with, but we’d risk arriving too early for the switch of winds at Cape Farewell.

Diana took the first watch just after 2 AM after we cleared the hazards on the north side of the entrance to Milford and could head more directly north. “Really cold, icy hands,” she wrote in the margins of the logbook. “Overcast skies heading further out to clear Arawua Point/Big Bay Bluff.” Just after sunrise on my watch, I got a glimpse of the mountains south of Mt Aspiring, which reminded me of Wyatt’s 100 mile run the length Aspiring National Park. I wondered if he could have seen the Tasman Sea from any of those lofty ridge lines he traversed?

Also in the logbook, I see a lot of scribbles in these notes about fuel rates, and estimates of actual fuel burned for miles ‘made good.’ Allora carries 190 gallons full which is more than enough for the distance as long as the weather is reasonably cooperative, but it makes a difference if you’re burning 1.5 gallons/hour or pushing the engine and burning 2.5 gallons/hour. The extra gallon doesn’t double your speed. People better at the maths would probably be able to calculate exactly what fuel rate is most efficient. I settled upon 1.6 or 1.7 as an nice compromise of efficiency, speed (to make our date at Cape Farewell) and comfort.

We had rain. We had current steadily set against us. We had dolphins streak by in the night leaving comet trails in the bioluminescence. We fussed about the wind, almost-but-not-quite-enough to sail, ever creeping up on the nose. We almost lost a batten in the mainsail. Then later, Otto, our autopilot made a sudden decision to turn hard to starboard out of nowhere. The switch for the high pressure pump on the watermaker heated up and set off the smoke alarm (naturally at night-while I was off watch). We saw no other boats besides the occasional fishing boat working closer to shore. We caught a glimpse of Aoraki (Mt Cook) at sunset, and at Cape Foulwind a couple of seal lions waved as we passed by.

On the last night, as seems to be a theme lately, Diana drew the toughest watch of the passage. There was just no way to completely avoid a patch of heavy winds slated to meet us as we approached the Cape, straight on the nose. We tried to time it for the least possible, but Poseidon wasn’t going to let us off feeling too clever. For her whole watch, Allora slammed into 20 knots on the bow clawing her way up the last bit of coast to Cape Farewell. Finally, after calling Farewell Maritime radio to try to find out whether it was generally considered advisable to cut the corner at Kahurangi shoals (which they weren’t really able to commit to), we decided it probably wasn’t, so we slogged on. Diana went off watch and very soon after, we were able to fall off the wind. Just five degrees made a big difference. Pretty soon we were motor-sailing and by Diana’s last sunrise watch she was able to shut the engine off and sail along Farewell Spit, an amazing 25km sandbank off the northwestern corner of the South Island at the opening of Cook Strait. The winds were light but sweet. Finally! ~MS

A quick blink in Bligh Sound/Hawea, – Fiordland

Caswell/Tai Te Timu Sound – the 45th parallel – Fiordland

Big Fish

a big fish lived here

under this rock

in this sound

70 meters of water

down down down

finning the murky fathoms

there must be something it is like to be

a big fish

broad tail to the tide

jaw slowly moving, gills filtering

oxygen and salt from darkness

listening to the strange whirr of a prop churning distantly overhead

scent in the current

vibrations of much younger, much smaller, more foolish fish

everyone makes mistakes

joy to the world!

big fish on!

the breathless mystery of something deep

that unremitting pull of an invisible line

uncompromising bite and stick and metal barb

is there hoping it might break free

what is it like

to be another’s flesh and dinner?

exhausted thrashing on the surface

searing bright light and fierce dryness

the gaseous, ethereal world

where white birds like cherubs flitter and follow

where albatross glide like shadows of another understanding

what is it like, big fish?

now that two men hold you in firm hands

knife wielding hands

careless hands

is this the dance?

waves surge against the rocks

seaweed starfish worms green saltwater alive

o’ fish shaped wave

these men call you big fish

men who came to find things to take

big trees all in a row

is there something it is like

to be a man holding a gray dead fish

for a picture

flesh stripped from her ancient bones ~MS

Northward to Charles/Taiporoporo Sound, Mesmerizing – Fiordland

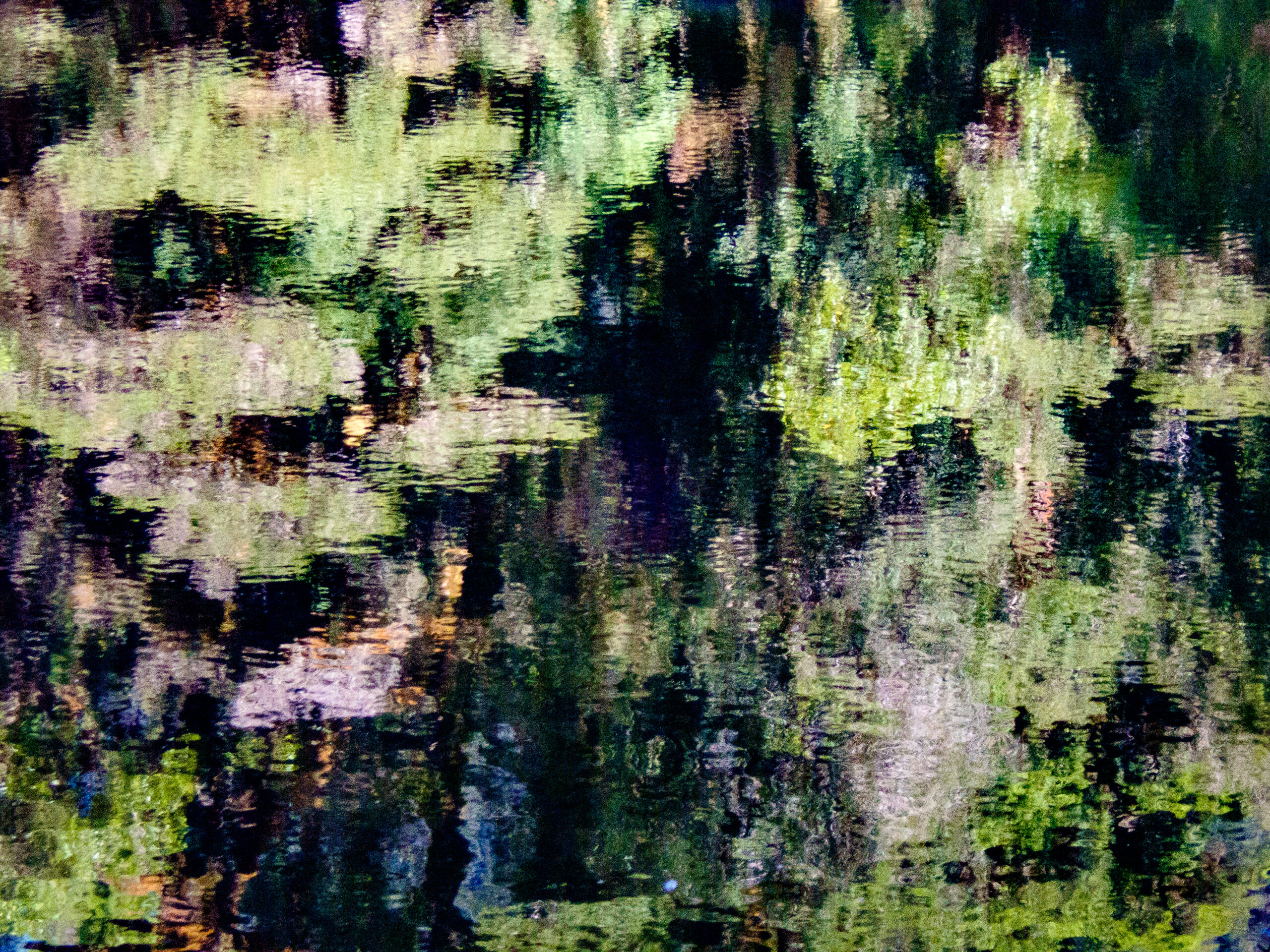

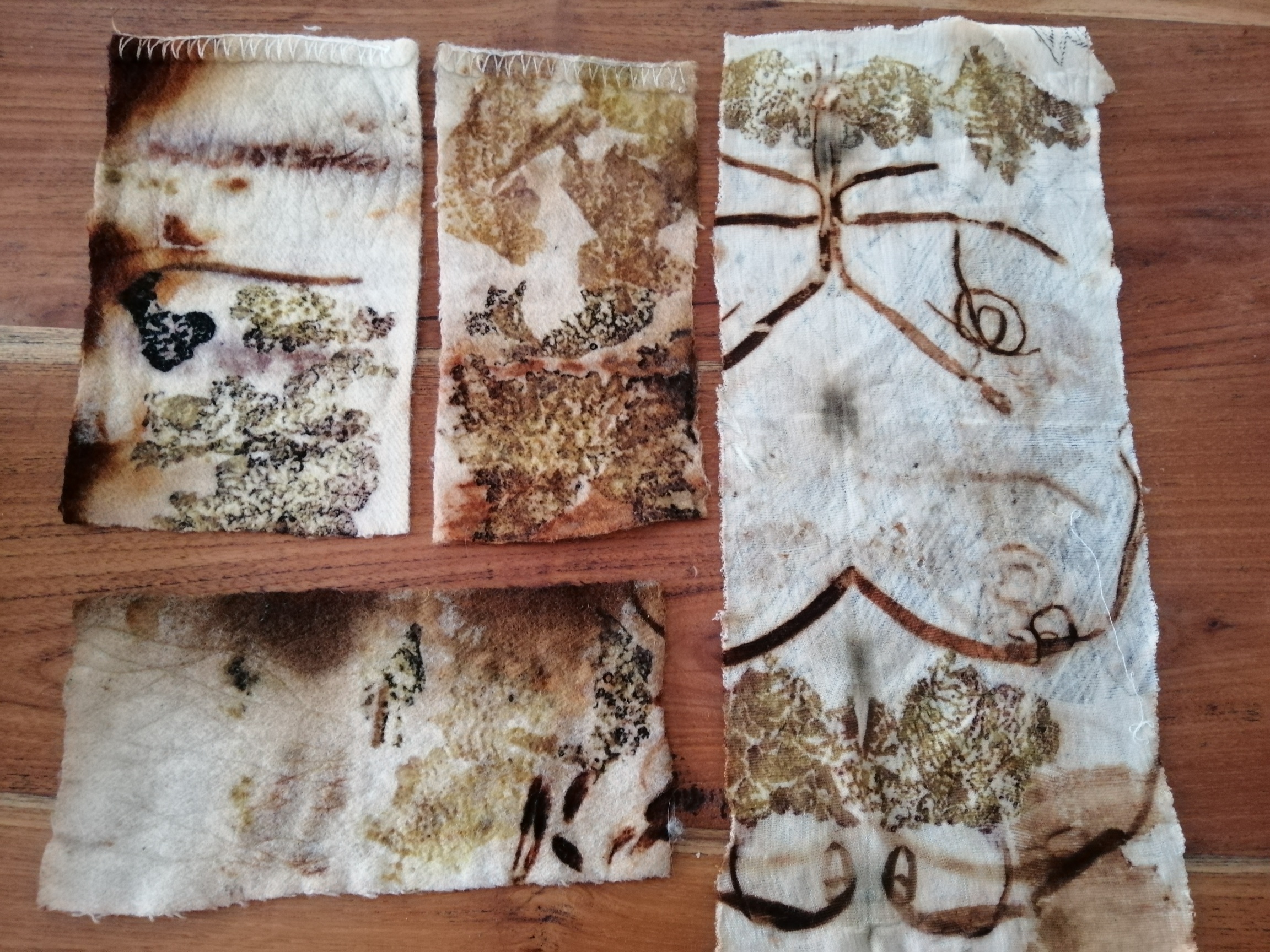

Abstracts

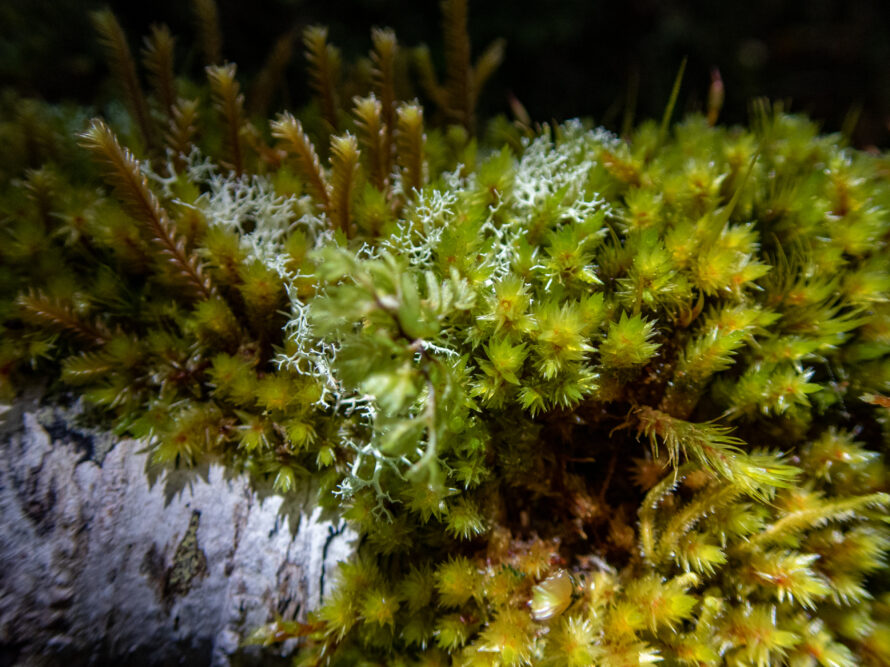

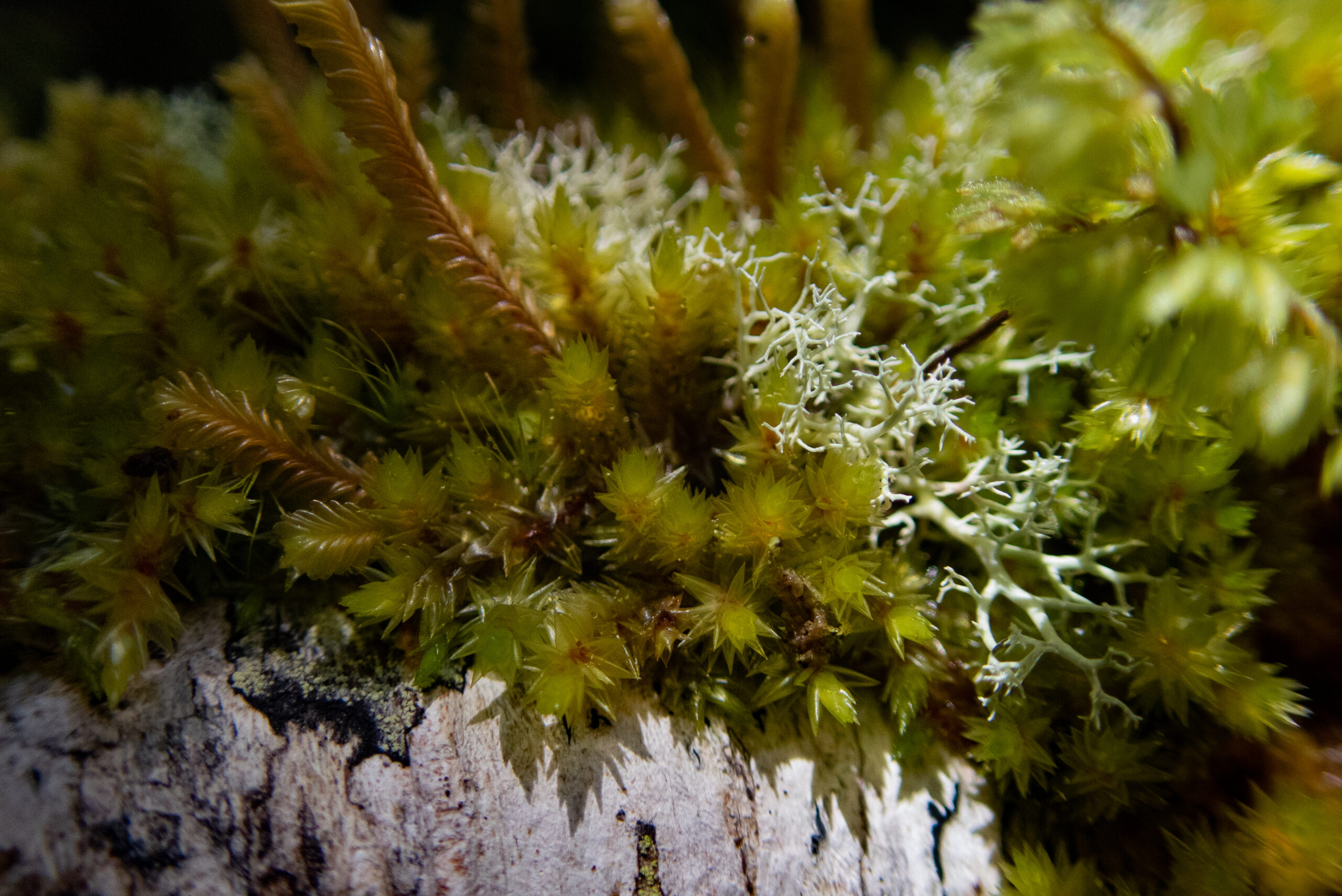

My favorite of Diana’s photographs from Fiordland are the “abstracts,” which she discovers by looking in a very careful, unique way, at the tidal line along the rocks, that magical transitional space between the hidden world underwater and the green, vibrant life-on-fire world above. Bare stone, stained and painted with time and color, bent and reflected by the still, secret, freshwater shimmering over the tide, the infinite, creative capacity of nature. Diana uses framing to share this vision, to point out Nature’s mastery of abstract art. It’s no surprise (and no accident) that these images feel so profoundly connected to her mosaic work. Most of the time these photographic expeditions are her solo meditations, which she shares with me when she gets back to Allora (after hours in the kayak!). But I’ve also been with her, paddling Namo gently into position, sitting right next to her, appreciating the wholeness of a beautiful place but without quite seeing what she is seeing. These images, for me, represent a particular (and particularly magical) collaboration between Diana and this very, very special world we are navigating in Fiordland.~MS

Doubtful/Patea, aka Gleeful Sound – Fiordland

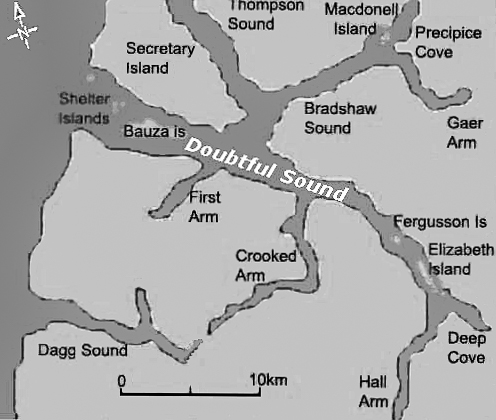

Dash from Dagg to Doubtful:

The relatively short distances between sounds along Fiordland’s rugged coast allow for mad dashes timed to brief calms, but you can’t really read the ocean’s mood sheltered in the steep granite walls of the fiords. Often the designation, “all weather anchorage,” means that fishermen have figured out that even in the worst conditions, certain spots are spared. The only way to know when it’s time to go, if you don’t have the benefit of years of local knowledge, is to study the weather models that we download twice a day from PredictWind. Because they are downloading via Iridium satellite, the resolution of the models cannot be higher that 50km. So there’s a bit of an odd effect as the models average how much the wind on the Tasman Sea is slowed down by the mountainous Fiordland coast, giving the appearance of lighter winds close to shore. They probably are a little lighter compared to what they are 20 miles out at sea, but our experience is that the models generally underestimate what it’s like on the outside and overestimate what we’ll experience once inside. Wind or no, gale or no, the seas are almost always a mess, particularly where local winds funnel through the openings of the sounds. Schedules are well known as the bane of sailing but in the land based world they are unavoidable, and Wyatt had a particularly narrow window of time to squeeze in a visit to us amid preparations to leave New Zealand. So we considered ourselves unreasonably lucky when the wind that pinned us down for a couple of days in Daag, relented in perfect time for us to make the dash. We arrived at the opening of Doubtful with what Wyatt would call a ‘splitter bluebird’ sunny day. ~MS

Allora on a mooring (all by herself) in Doubtful Sound, tucked right up next to the roar of Helena Falls. Evening spent getting the aft cabin clear of STUFF to welcome Wyatt the next day. Here, I don the particular ‘happy parent’ expression, just moments after snagging Wyatt off the bus!

Yep, the same one!

Ha, Wyatt caught us both entranced!

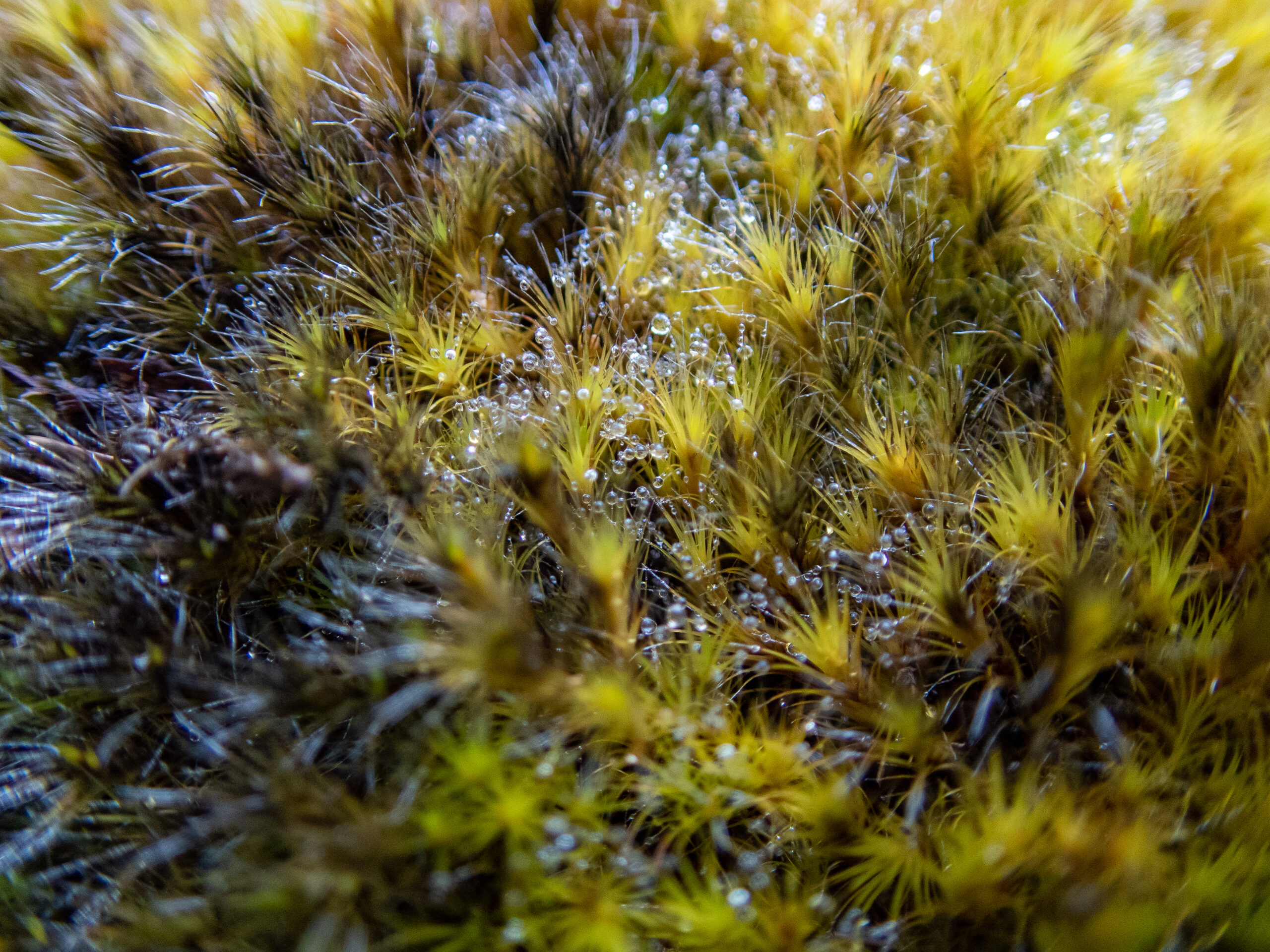

We have experienced a profound cumulative effect traveling through the wilderness of these southern fiords, as we mash through the tangled forest or glide like a whisper through glassy, watery mountain reflections. We feel a growing, deepening awareness of the liveness and power of this unfettered place. Every day Diana peers a little closer into the magical profusion of the rainforest, its tiniest creatures (or the smallest we may perceive) all this abundance of life fueled by fresh water, gray stormy clouds, shifting rays of sunlight, massive stone faces fading softly into the distance. The boundless imagination of nature is vividly accessible here, free of scheming human interference. Inexhaustible, effortless celebration. We feel blessed to feel like we belong, to participate at our particular scale, with our particular way of perceiving. Gratefully reconnected as dolphins come to play alongside Allora, turn and smile and look back at us with familiar eyes, into our own delighted gaze. As the sky softens at sunset, or looms heavy with rain before the storm, as water gushes from waterfalls that were not there before the deluge, thundering into the fiord, as williwaws tornado in wild rainbow mists across startled coves, how delightful it is to be alive, a part of, this marvelous, miraculous world. ~MS

We moved across Bradshaw Sound to Precipice Cove/MacDonnell Island, an all weather anchorage.

Still quite giddy about having one on one time with Wyatt before he flies back to the States.

Dagg/Te Ra Sound, shared only with Wapiti in the ‘roar.’ – Fiordland

‘Anchorage Arm’ and had glassy calm conditions. Instead of trying to find shallow enough depths in the middle to anchor in, we snugged up super close to shore utilizing some fishermen’s lines which are rigged in place. Wonderful protection from winds, mellifluous creek sounds and voracious sandflies!

Something happened when the twenty North American Wapiti Roosevelt gifted to New Zealand in 1905 found their way into the heart of Fiordland’s steep and impenetrable wilderness. Maybe there’s a perfectly rational scientific explanation (maybe it has something to do with crossing breeding with Red Deer?). They got a bit smaller than the fat and happy elk of Yellowstone (which certainly makes good sense given the dense rainforest) but they also changed their tune, no longer bugling with that iconic, haunting call that resonates across the frosty parklands, lodgepole forests and granite peaks of the Rockies. Our visit to Daag coincided with height of the “roar.” It’s a sound that does not “belong,” but also feels so fitting, as though giving voice to the thick ferny jungle of that unpeopled wilderness. Deep, guttural, plaintive and haunting (in their own way) – their roars echo across the still water and ridiculously precipitous canyon walls. You can hear individual stags make their way up and down the steep shore, and we paddled Namo as stealthily as we could manage along the shore hoping for a glimpse, and though they often seemed very close, we never saw them. We could only imagine their antlered heads tilted back, belly’s trembling as they gave voice to the wilderness.~MS

Although Spanish moss grows on trees, it is not a parasite. It doesn’t put down roots in the tree it grows on, nor does it take nutrients from it. The plant thrives on rain and fog, sunlight, and airborne or waterborne dust and debris.

Known for it’s friendly, ‘cheet cheet’ call and it’s crazy flying antics, the Fantail or Pīwakawaka often follows another animal (and people) to capture insects. Time and time again, though, they acted as guides; when we were off track in the woods, they’d appear, chirping energetically, as if to say, ‘no … not that way, THIS way!!’ I learned to always follow them!

Some fungi fun: I haven’t had the time to research ID’s on most of these, so write me if you know and are keen to share?!

Wet Jacket Arm, not just any Arm – Fiordland.

Lots to captivate ~ lingering rainbows, new waterfalls, breathtaking bush, dolphins and surreal reflections while moving up to the end of Wet Jacket Arm. I wrote these words in the logbook from that day: ‘OH MY GOODNESS – A VISUAL FEAST!’

Delightful Dusky/Tamatea Sound – Fiordland

Dusky is the longest and most extensive fiord in Fiordland at nearly 24 miles in length. Named ‘Dusky’ after Captain Cook’s evening sail by in 1770, and ‘Tamatea’ after the renown Māori explorer who spent much time there. He’s also known for the coining the longest name of a place near Hawke’s Bay ‘Taumatawhakatangihangakoauauotamateaturipukakapikimaungahoronukupokaiwhenuakitanatahu,’ so I’m glad I didn’t have to work that into our logbook! ~DS

Inner Luncheon Cove on Anchor Island, Dusky Sound

We are anchored in an 18th century naturalist’s illustration. The Kākā, subtly colored parrots, russet and carmine, gray and mossy green, chatter in mobs back and forth. Fur seals and their pups bawl and rumble along the densely wooded shore, draped on rocks, sunning just out of the vivid green tide, or hidden mysteriously in the forest. Rays and Broadnose Sevengill sharks patrol the shallows. Bellbirds chime and Wood Pigeons dive and soar in mating displays, wind whirring in their wings. The water is supernaturally still after the tumult and breaking swell of Broke Adrift Passage, and the long motor up the easing blue Pacific around Cape Providence. The scale of the world is abruptly more intimate. Captain Cook dined on crayfish here in 1773. He left behind a recipe for brewing beer from the bark of Rimu trees, molasses and yeast. The island is also predator free, and refuge to the rare ground parrot, the Kākāpō, once thought to be extinct – rediscovered in Port Pegasus, Stewart Island by Rodney Russ, a sailor/explorer we met in Christchurch.

A chance to sit on the bow and meditate outside, to the constant music of birds, “Here and now boys, here and now.”

The dearth of sandflies and still air made for a pleasant barbecue, cooking up fillets of the Albacore tuna we caught on our way into Dusky.

The trails on Anchor Island are named and well marked, though oddly, do not seem to clearly indicate which of the many paths lead to the lake (just a kilometer or two away). We weren’t very far along the “wrong” trail when a mob of Kaka settled noisly into the trees over our heads. We sat still and waited and they ventured closer and closer, sailing back and forth, gnawing at the branches with their strong beaks and then landed a few feet away, turning their heads upside down for a curious closer look. A South Island Robin/Kakaruai (re-introduced in 2002) also hopped over to say hello, as they do, finally summoning the courage to peck at the bottom of my shoe. ~MS

Fanny Cove, Dusky Sound

It was still when we arrived after the move from Anchor Island. Along the way we enjoyed the company of some of Dusky Sound’s residence Bottlenose dolphins, and stopped for a closer look at a waterfall, a hundred feet of depth under Allora’s keel a boat length or less from shore. We ate some bread that Diana pulled from the oven just as we entered the broad cove and thought about our plan for anchoring. The forecast was for twenty-five to thirty knots of northerly on the outside (a little less than the full Pusygar gale which prevails three hundred days out of a year), but all the models showed much less fifteen miles inland form the open sea. Still with the wind and williwas, we didn’t really know what we might get. The dramatic cove with the huge granite wall of Perpendicular Peak at the head is much bigger than in looks on the chart. The opposite of intimate Luncheon cove. We dropped in 60 feet of water and laid out all of our 100 meters of chain at a shallow angle along the shoreline, still sitting in thirty feet of water but with rocky shallows close by. Our first line would not really hold us off, and we ran a second as the wind came up and it was clear that the topography of cove seemed to twist the north wind with just a hint of west in it to solid west, coming at Allora from the port side and pushing us toward shore. The cove is big enough for a reasonable bit of fetch too, but the water on the east side is just too deep. Already worn out from setting the first two lines we debated putting out a second anchor from our midships cleat, but we worried about dealing with picking it back up if things got rough and we hand to move. We finally settled on putting out a third shore line using forty feet of chain to tie around a rock and pulled that up tight. By then the wind was pushing us with gusts of 18 knots. It went against every sailor instinct to be holding off a lee shore this way, but as long as our lines held it would take some mighty force indeed to drag 100 meters of chain and an anchor uphill. A power boat came in, and poked around on the east side and dropped anchor along the east side which we thought was too deep and we briefly wondered if we’d read the situation wrong (having no advice in our books about where to anchor in this broad open cove). But then they sent a dinghy over and we recognized the driver as he approached. Junate! from Hokey Pokey, a catamaran we knew from Papeete and the Gambier! We shared a brief excited catch-up about the last three years before he headed back. They’d also decided that it was too deep to anchor on the more protected east side and were zooming off (as only a power boat may) to find a mooring in another cove, much too far away for us to make before dark. And we were left alone with the wind, checking our shorelines and worrying how much more the night would bring. Just before dark the wind gusted to the mid twenties and Allora settled back about fifteen feet closer to shore than she had been. Our starboard shoreline went momentarily slack and the depth rose to twenty five feet. It began to rain. We donned foulies and went on deck ready to take more drastic action if it turned out that our anchor was actually not holding. We tightened up the breast line chained to the rock to pull us out into deeper water, and checked the GPS. We finally decided that the low tide had allowed some slack in our chain which the gusts shook out and we were holding fine. We made sure the dishes were away and everything was ship shape for the night, just in case, and then the wind quit completely, the rain settled in gently. In the middle of the night we woke up to an amazing stillness, just the finest pitter patter of rain. Light from a still nearly full moon softly lit the stunning granite faces that guard the entrance to the cove and the fine rain softened their reflection in the still water. It felt like a big reassuring landscape hug for a wonderful, still, uneventful night of sleep. ~MS

Seaforth River, Dusky Sound

It took us three tries to get the anchor to hold in Shark Cove. Communication from bow (Diana) to the helm (Marcus) is always a bit challenging (West Marine sells headsets called “marriage savers”). The view is different, too. We did alright for the first couple of attempted sets, but both got a little impatient and grumpy by the third. It held, and we were finally tied up, but tired and neither of us feeling great about how the teamwork had held up. There’s a lot at stake — sudden weather switches, unpredictable williwaws make it crucial to get this right. Every couple of days we get another chance to see if we can improve on our mutual desire to work together.

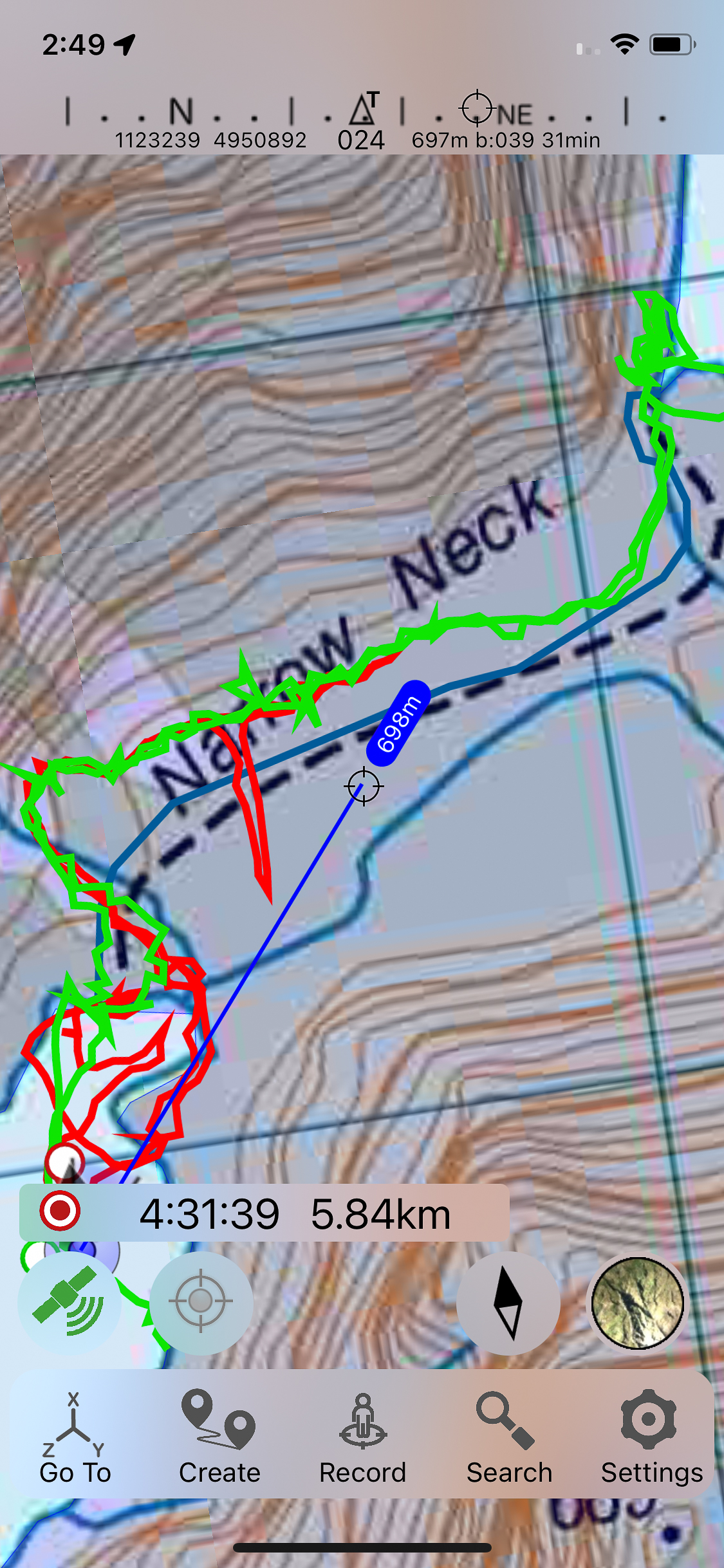

We got a little of a late start for the longish dinghy ride over to Supper Cove where the Seaforth River enters the Sound. It’s reported to hold brown trout! The Dusky trail slopes along the banks, through mud puddles and a podocarp forest of magnificent rimu, kahikatea, miro, mataī and tōtara trees. The river tumbles off some boulders and then flattens like a lake for several kilometers. Tea stained with tannins, spotting fish (the only way to fish in New Zealand) was tough. Ultimately we didn’t see any, though a few rocks got some very intense attention.~MS  We took Namo over to the next bay, Supper Cove, to be able to hike on the Dusky Track. It’s an advanced tramper track – 84km one way, but we just did 6km and found it muddy but heavenly (not bushwhacking).

We took Namo over to the next bay, Supper Cove, to be able to hike on the Dusky Track. It’s an advanced tramper track – 84km one way, but we just did 6km and found it muddy but heavenly (not bushwhacking).

While Wet Jacket Arm and Breaksea Sound are still part of the Dusky/Tamatea Complex, I’ve broken them up, if for no other reason than my own sanity, so I can feel a sense of progression, ha! ~DS

“Whales! One o’clock, Starboard bow! Not that far!”

There isn’t much about humpback’s that you can get “used” to

fin and back slipping above the waves

scale inspires awe

flukes waving goodbye, whispering into the drink

surge of whales on the move

juvenile males on a mission

shouldering water ahead of them as they porpoise on the surface

strange knobby heads rushing through the foam

in calmer water, a spy hop, slipping up to peak at YOU

soft blow of a sleeping whale

the sudden totally unexpected wild audacity of a breach

that always always comes out of nowhere

and again

young whale under the stand up paddle board

gripping the camera, ready to go under

calves in the anchorage, sleeping with Mom

arced above her head

curious little ones spy hopping by the stern

or practicing their breaches

flopping, silly half out

then the day they show everyone what they’ve got

~MS

(Rough camera moves, sorry, but the proximity had us sufficiently EXCITED!!!)

The Bird Motus of Penrhyn, Cook Islands

Mad for Kio Kio, bonefishing in Penrhyn

Every fisherman dreams about a secret fishing hole somewhere. Someplace no one knows about. No one goes. No one (or hardly anyone) has ever fished. A place where you show up knowing you won’t see a single soul and that the fish have never seen a fly. This dream fishing spot is naturally chock full of fish, too, everywhere you turn.

Every fisherman dreams about a secret fishing hole somewhere. Someplace no one knows about. No one goes. No one (or hardly anyone) has ever fished. A place where you show up knowing you won’t see a single soul and that the fish have never seen a fly. This dream fishing spot is naturally chock full of fish, too, everywhere you turn.

The Cook Island’s atoll, Penrhyn, might just be that place.

This atoll lays more than 800 miles of open ocean from anywhere. There are no flights. It is visited by just two supply ships a year. The only way to get here is in your own boat, sailing far off of the normal tradewind route. There was a time when expensive flights from the main islands of the Cooks occasionally brought an intrepid fly fishermen from New Zealand, though because there are no hotels or any other tourist infrastructure on Penrhyn the only way to fish these remote flats, even then, was to stay as a guest with the pastor at Te Tautua and have him take you. This apparently did happen at least once. Years ago. Basically, the only people who ever visit, in very, very small numbers are sailors. The intersection of committed bonefishermen and blue-water sailors who can actually get themselves to Penrhyn yields a very tiny slice of humanity. I’d bet there aren’t more than about five of us in the whole world, and that includes our friend Mike, who’s introduction to fly fishing was walking the flats with me in the Gambier and Rangiroa.

The pastor insisted on taking us to his spot, though we had our own dinghy and knew from Google Earth exactly where to go. Wishing to be gracious guests of the island, we accepted the ride. We spotted the first pod of fish even before getting out of the boats and over the next four hours (the limit of the pastor’s desire to stay and harvest noddy bird eggs), I landed at least fifteen bonefish (which is a lot of bonefish), considering the amount of time it takes to land each one and the fact that a fighting ‘kio-kio’ clears the immediate area on the flat of willing fish. Mike caught nearly that many, as well, and we were often doubled up with fish on at the same time.

We fished this singular spot for a couple weeks going back on our own, and it wasn’t always as good as the first day, the tide and the weather have a lot to say about how good the fishing is going to be, but it was always our spot and the fish were always there. They aren’t as big on average as the bonefish in French Polynesia, but Penrhyn is chock full of them.

We pinched ourselves regularly to make sure it was not just a dream. ~MS

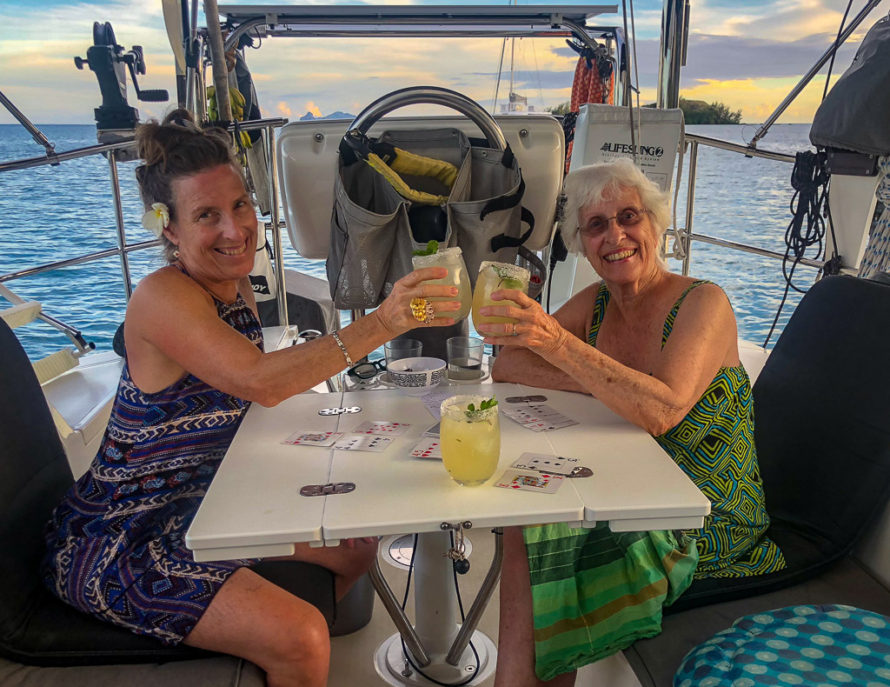

Mom and Lori team up in the Gambier!

Our 2019 ‘cyclone season’ in the Gambier kicked off with visits from our Mom’s and sisters. Mom and Lori arrived at the end of January and we enjoyed a couple of weeks aboard Allora, sharing our favorites (people and places) in this sweet eastern corner of French Polynesia.

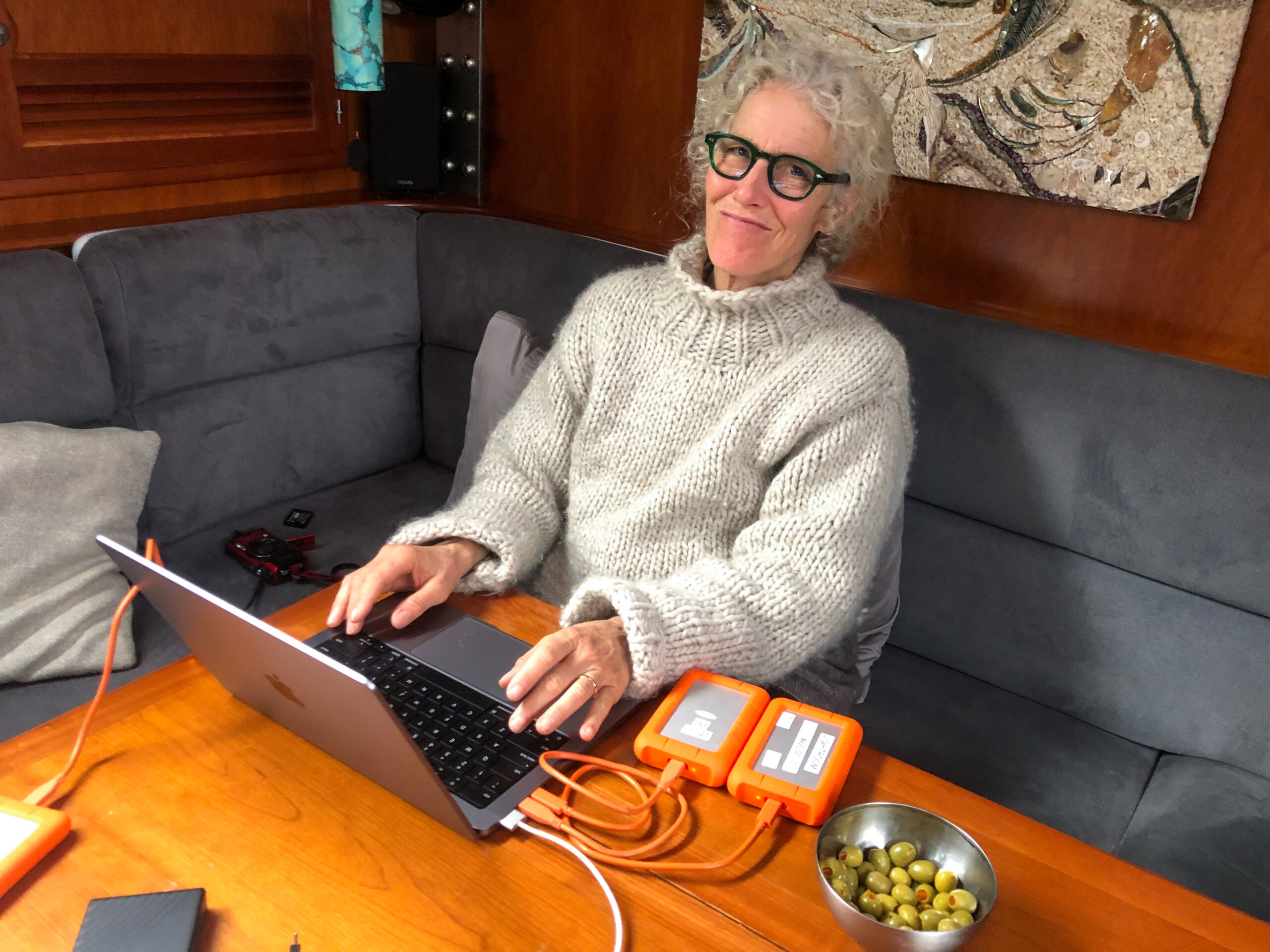

Mom certainly knows her way around the boat, so she slips into very relaxed mode and we always marvel at her being ‘game’ to do just about anything. This was Lori’s first full-fledged stay aboard, so it was particularly wonderful to immerse her in our life afloat. These were full, rich days!!! ~DS

Through Lori’s Lens:

Through Wyatt’s Lens, Gambier, 2019

NEVER Too Many Whales!

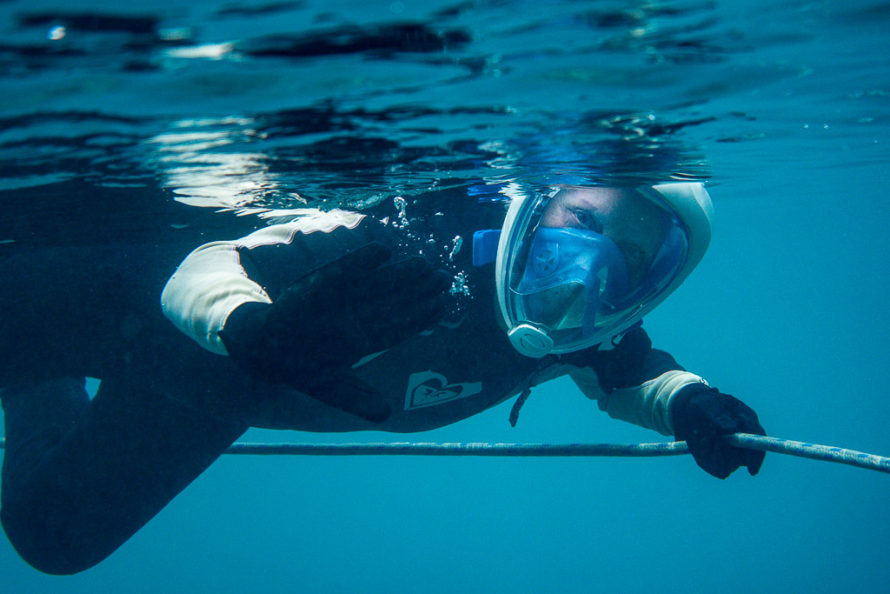

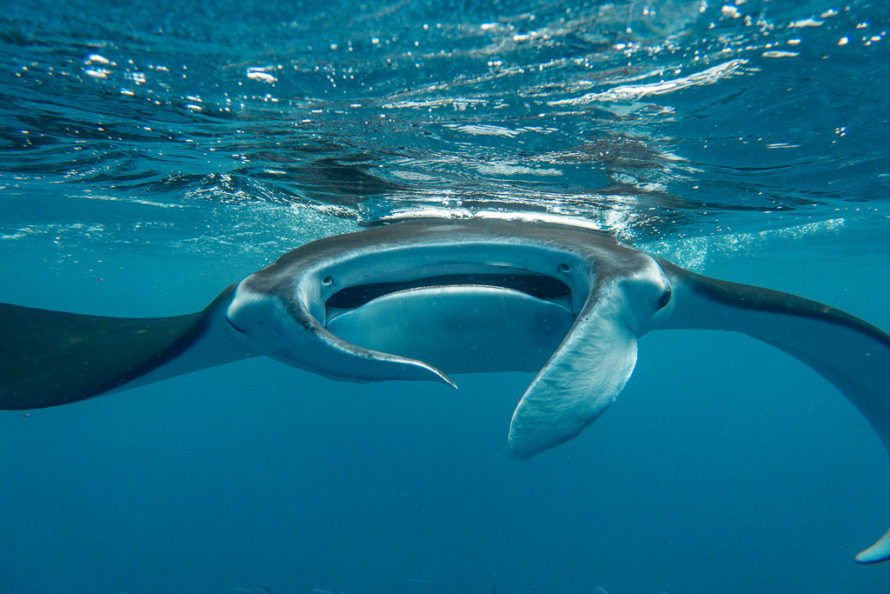

Manta LOVE in Tikehau, Tuamotus

Pictures are going to do most of the talking here. Just think about the size of these amazing creatures, ten, twelve feet wing span (Manta Alfredi get up to 18’ across). Watching them move, like huge underwater birds, is mesmerizing. One bunch of six or seven literally bowled us over. You can find them in this spot pretty reliably because it’s a cleaning station. Diana was hooked. Another boat came to join us, Jacaranda, who we knew from their blog and got to know on the Single-Sideband radio net that covers this part of the South Pacfic (called the Polynesian Magellan Net, at 8173 USB, 0800 and 0600 local time). Linda is as crazy about looking for new fish as Diana, and she and Chuck had some amazing experiences hanging out with Manta researches on the remote island of Socorro in Mexico. I spent the morning writing, but Diana and her dive buddies got out with the Mantas early each morning. During one of their best sessions they watched a pair doing a courtship dance and then mating which is a rare thing to observe in the wild.

Diana dove with the Mantas twice a day for the week we hung out and took, you might imagine, thousands of pictures. Some of those she sent to an organization called the Manta Trust, (https://www.mantatrust.org) which uses the unique patterns of spots on a Manta’s belly to identify individuals. They encourage people to send in their photos, and then experts in each region identify and catalogue them. Diana sent them pictures of seven distinct individuals. Six of them had been identified before, and they shared some of the information they had from previous sightings, where when, doing what. One of them was brand new to the researchers. They told Diana that they have identified 70 mantas just in Tikehau, so now that’s 71. The next fun part, was that all seven had numbers for identification but needed names. So Diana gave them Polynesian names. Haley’s boyfriend suggested that ‘Liam the Manta’ would make a fine name, though inspiring a Manta name as that would be, it did not make the final cut.

Meet the Mantas:

Ma taa raara – (A shining, or bright eye)

Vavevave – (Speedily!)

Atae – (Surprise)

Marema re – (Sparkling as the saltwater at night)

Tamure – (Dance Together)

Atavai – (Elegant)

Manino – (Calm, Smooth)

Polynesian beauty with an Emperorfish. I brought the dinghy over to say hi and see what they were up to and she shared two fish with us for dinner.

Rangiroa -The Tuamotu Folks Have Heard Of

Our first instinct, on our initial pass through the Tuamotus last year, was to avoid Rangiroa. It seemed too popular – with actual hotels for tourists, including those ‘elegant’ thatched roof bungalows out over the water that plague Bora Bora. But on our second pass this year, we ended up spending a month in this largest of the Tuamotus atolls.

I’ll keep my part of the motivation for staying so long to one sentence: Rangiroa has the best bonefishing in the Tuamotus. Okay, moving on. Okay, well maybe not moving on. I broke both my nine and eight weight rods on these fish. I used up my entire stock of number 4 hooks. I fished everyday, and there were bonefish wherever we went, even at the touristy Blue Lagoon. We’re not talking armies of tourists, lets say a couple dozen for a whole day in three or four small boats. One group even waved me over and fed me lunch. The tour operator was an avid fisherman and pure Polynesian friendly. He told about a spot where he’d seen a giant bonefish, so big that at first he’d mistaken it for a shark.

Unfortunately, I never got over there. The wind shifted and we had to pull up anchor – which is a short sentence for describing a pretty harrowing situation where our anchor windlass failed, and we had to untangle the anchor from some nasty bottom, manually, and then with a little luck and jimmying of the windlass control, we raised the Rocna, just as the waves and wind built in earnest. Fortunately, we figured out the wiring problem at the next anchorage and it was an easy repair. ~MS

Pacific Ocean Crossing

Galapagos to the Marquesas Islands, French Polynesia 4/25 – 5/13/17

It’s been 6 months since Allora’s first ocean crossing. I am writing this from French Polynesia, eking out the time and wifi to finally share this treasury of experience. Gathering our 3 kids, Haley, Madison and Wyatt, as crew (we call them, ‘GREM’, to be explained later) was ideal and a bit of a miracle at this point in their busy and widespread lives. I have to say, I love that it felt imperative to each of them to make the voyage – what adventurous souls! Haley had already crossed the Indian Ocean with SeaMester; I think she knew something of the quiet and solitude we’d be experiencing.

We’re family, yes, but in this experience, we formed an alliance, a team. I was reminded of leaving Montana to live in Ravenna, Italia; we were drop shipped into a new culture – it was palpable, the intense newness of it all – but after that year, our family had shared something indefinably rich. Here, out on the illimitable sea, we truly relied on each other once again to ‘navigate the waters.’ Though I think each of us came away with an impression that also felt wholly personal, as I look back at those sweet days, I see a point in time in which we were able to slip into an eddy in our lives, to come together and share this magic – we were uncertain and proud, bored and content, tired and euphoric, collectively.

I hope to always recall the slow but sure rhythm of these 18 sweet days. My mosaic work often feels like this – bit by bit, piece by piece and one day, something’s manifested. In this case, we, with the wind, landed in paradise, Fatu Hiva, Marquesas. ~DS

Stats:

Distance: 2,956nm (3,401miles)

Avg. speed from Isla Isabela, Galapagos to Fatu Hiva, Marquesas: 6.895 knots/hr (7.9 mph)

Avg. 24 hr distance: 165nm (189.8 miles)

I’ve been thinking about the tuna I killed

the exhausted fish bleeding into the water

after our gaff cut its gill then came apart and fell overboard

clouds of blood, Maddi thought of whaling

what it would be like on another scale

the rivers of whale ichor gushing into this exact ocean

from a heart bigger than all five of us

even this, probably average tuna, appears from its deep refuge like a giant

the mass of muscle that challenged our arms despite enormous mechanical advantage

We confounded the powerful, sleek prince of blue water

though we cannot actually lift him, but barely heave him aboard

like a deer drug through the snow

our muscles are spent

chunks of sashimi as big as an elk quarter

deep in the cheek, beautiful stuff I could, should eat from my knife even as I filet

I never ate deer raw

I worry I may one day think I have taken something I shouldn’t have

more than is left to take

for a man living in a world where food is easy

taken invisibly with efficient economic precision

swaddled in styrofoam and plastic

a big mac or burrata

seared tuna or sushi

for anyone who indulges a whim

anywhere, anytime

even in places that in my lifetime once offered only boiled meat and potatoes

peaches and apricots in the season of miller moths beating against the screen door

the man across the street in Hillrose, Colorado had collections of arrowheads

chipped stone for killing, scraping and digging

New technology just a few decades or a century ago

Here we see white fishing boats with towers for spotting the game

powerful motors for dragging it from the deep

fishermen like whalers still, raw

distant lives, sheltered by unquestioning pragmatism

shortsighted, strong armed servants of a frivolous city dwelling species

below us shifts Melville’s eternal blue noon

the multitude of shades of azure

that would have names if we were like eskimos naming snow

it all deepens to black

red squid and sperm whales

all that’s left of the world falls like ash into the deepest sea

~MS