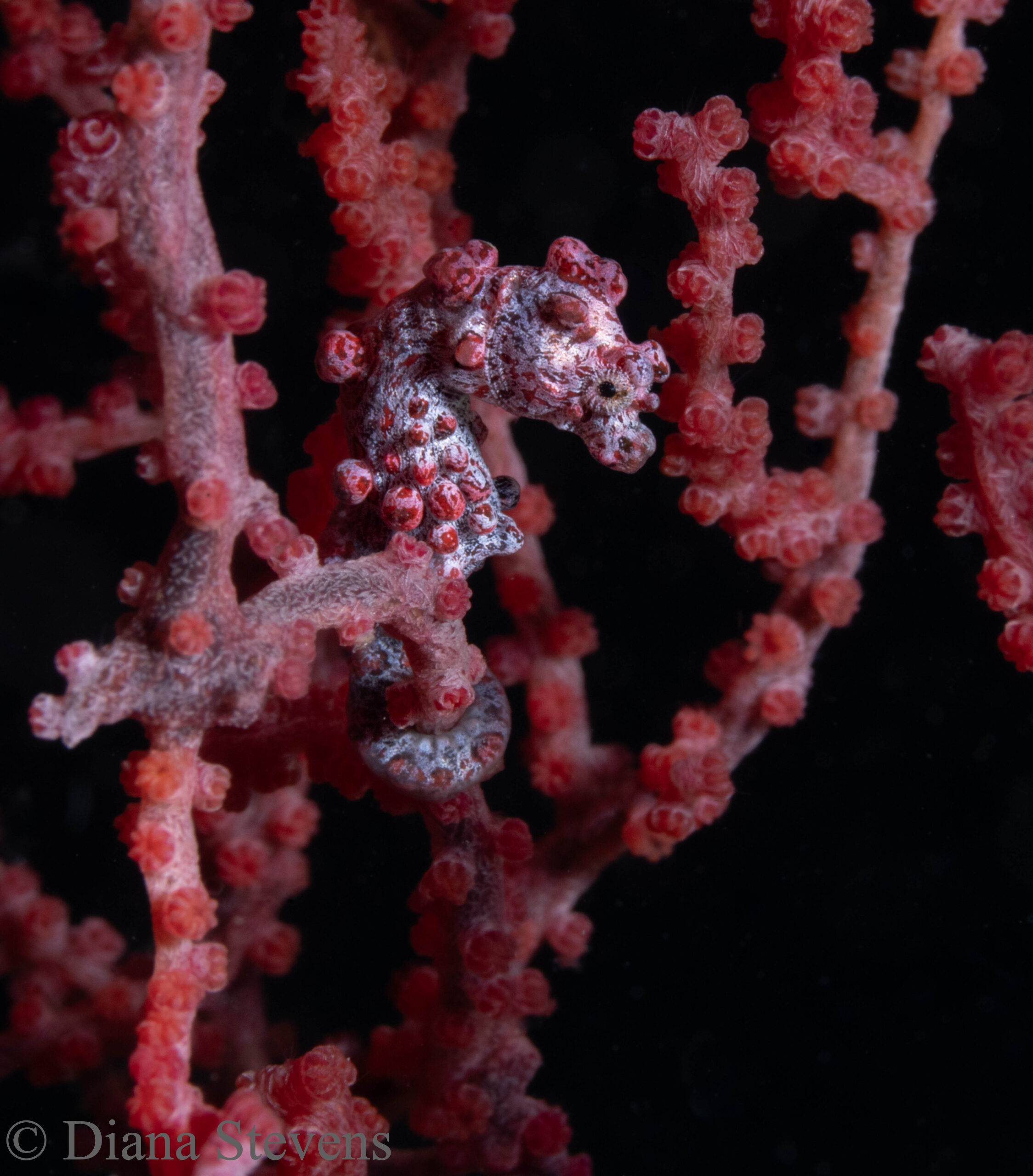

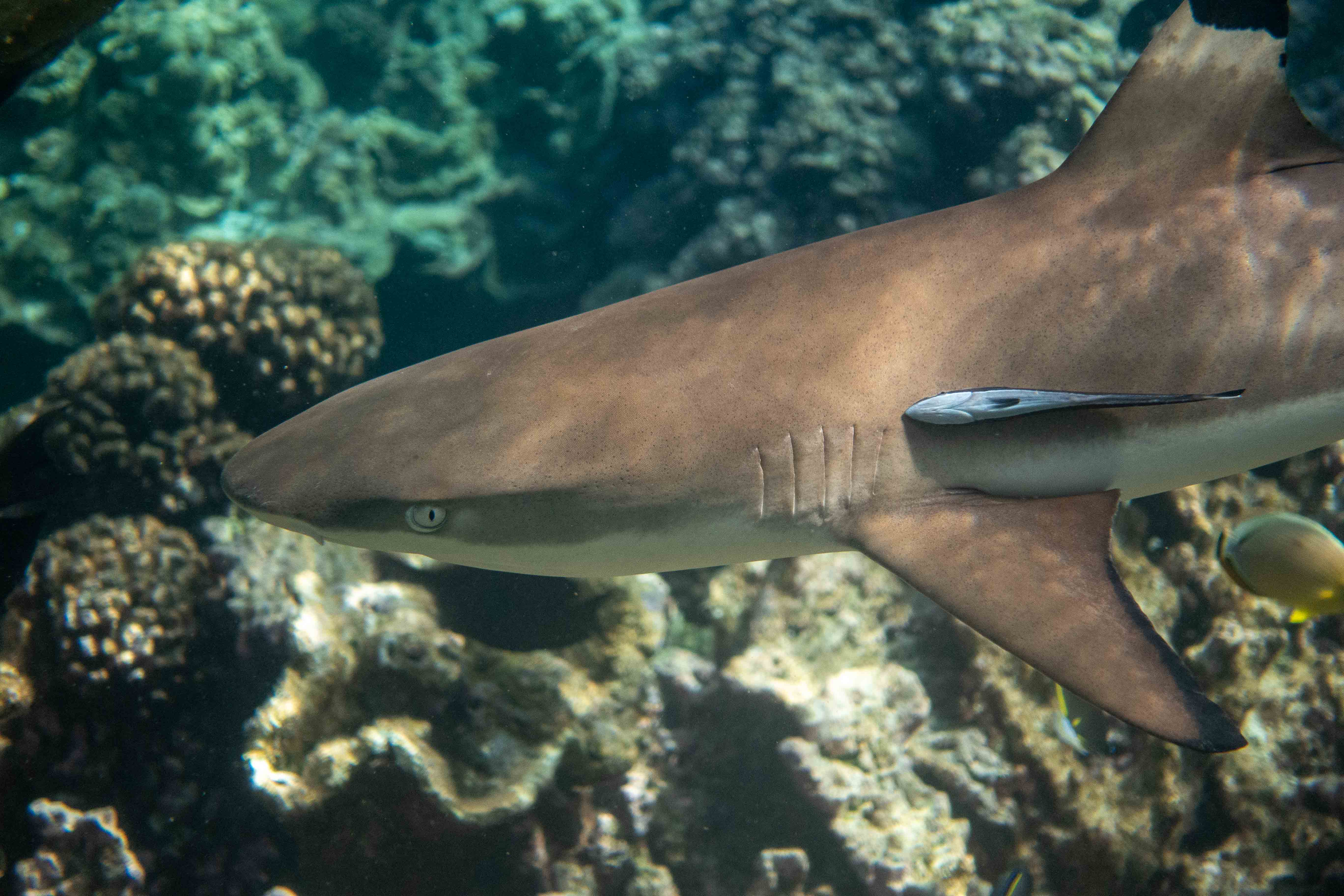

The final Lembeh Strait muck diving album (see the previous two posts for more crazy creatures from these murky waters).

Tag: Nirvana

Start MUCKING around!

Muck diving is not for everyone. Turns out it’s pretty much what it sounds like, no matter what Diana (and especially her photographs) will try to tell you. Fortunately, at least in Lembeh Strait, Sulawesi, the water’s warm and the visibility is just slightly better than the name conjures. If you go with a dive resort, normal dives times are around sixty minutes. Unfortunately (for me) we didn’t have that restriction, and due to regrettable advances in battery technology and Diana’s ability to forego breathing for extraordinary lengths of time, muck dives with her can run over two hours. I have a bit more blood to keep oxygenated, so I typically get a (usually pleasant) half hour nap in the dinghy at the end of the dive. So not quite two hours in featureless gloom, scouring the rubble and muck for creatures mostly too small for my aging eyes to see even when they are pointed out to me.

Muck diving is not for everyone. Turns out it’s pretty much what it sounds like, no matter what Diana (and especially her photographs) will try to tell you. Fortunately, at least in Lembeh Strait, Sulawesi, the water’s warm and the visibility is just slightly better than the name conjures. If you go with a dive resort, normal dives times are around sixty minutes. Unfortunately (for me) we didn’t have that restriction, and due to regrettable advances in battery technology and Diana’s ability to forego breathing for extraordinary lengths of time, muck dives with her can run over two hours. I have a bit more blood to keep oxygenated, so I typically get a (usually pleasant) half hour nap in the dinghy at the end of the dive. So not quite two hours in featureless gloom, scouring the rubble and muck for creatures mostly too small for my aging eyes to see even when they are pointed out to me.

And yet, I would spend a week in the muck anytime, for the chance to see, in person, two Painted Frog Fish holding hands twenty meters deep in the Celebes Sea. I’m so very happy to live in a universe where that is a thing.

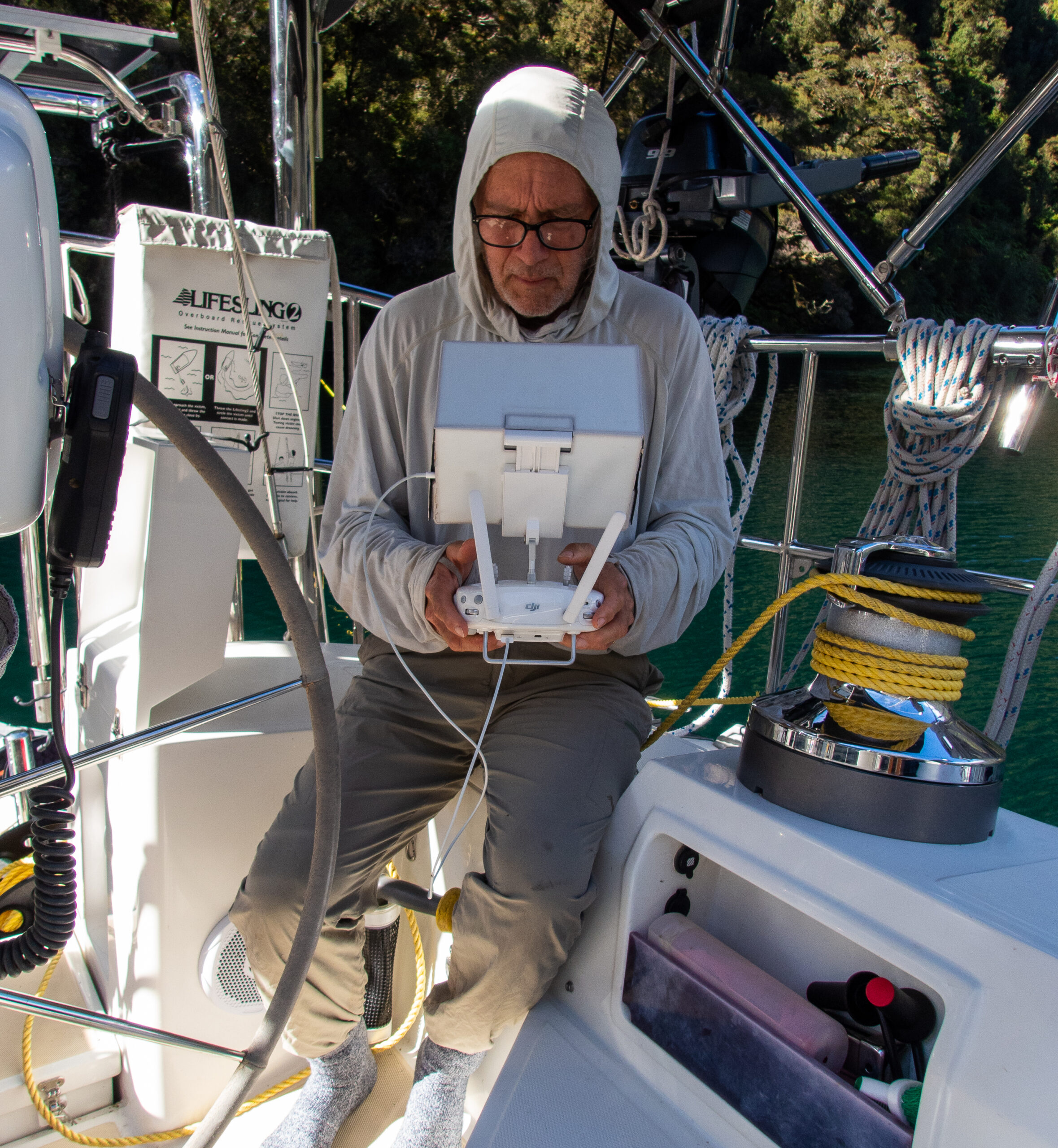

In Lembeh, Diana arranged for a guide which was crucial. Lembeh Resort (phenomenal outfit in every way) set us up with Sandro, a star on their crew, originally from central Sulawesi. He was absolutely delightful to hang out with for six days of diving; easy-going but also a very motivated, perfectly happy to squeeze into Namo – with tanks and gear for three divers – and wallow across the strait at dinghy speed while the professional dive boat he would normally have been on whizzes by. He did occasionally wonder aloud about what might happen if we came up and Namo wasn’t there (with no one to tend to her), but otherwise he was game for diving without a proper boat and happy to stay under for two hours if Diana’s batteries lasted that long. He’s been guiding in Lembeh for years, having worked his way up from being the personal gardener for the dive shop owner, and he’s obviously still fascinated with muck diving. He carried an erasable slate and enthusiastically wrote down names for what he was pointing out to us (often with the proper Latin name). He has a particular interest in photography and works with Lembeh Critter’s camera operation (training other guides and shooting in his spare time) so besides spotting unimaginable, tiny camouflaged creatures buried in the muck, he also was able to help Diana learn how to use the snoot on her strobe light, which gives some of these photographs their dramatic look.

It’s basically impossible to adequately describe how difficult underwater photography is. Start with the idea that literally everything is approximately seventy-nine times harder to do underwater (except maybe peeing in your wetsuit). Buoyancy is super tricky because if you stir up the muck you can’t take photos anymore, and there are seriously dangerous creatures buried invisibly in the sand where you would like to brace your knee. Looking through the viewfinder with goggles is significantly tougher than it might sound (and it should sound impossible). Sony’s “smart” autofocus system hasn’t been down there before either and typically just throws its hands up in the (water?) unless it’s really lucky to recognize an eye. Many of the creatures who’ve developed their camouflage over literally billions of years of evolution are also smaller than a dime, so depth of field is harrowingly scant (breathe and you’ll miss the shot). You’re wearing gloves (for safety), so adjusting things like your f-stop, shutter speed, strobe power or ISO is extra fun. And, of course, though some of these critters do sit still, there’s the usual unpredictability that comes with photographing wild things. I could go on. Basically it’s like the mosaic work Diana does, in that it requires an intensity of focus and bull-doggedness that lies far outside of any normally agreed upon bounds of sanity.

Enjoy the photos (comments are welcome), but also watch the behind the scene’s video I made of Diana and Sandro doing their thing, so you don’t get the wrong idea. ~MS

Farewell New Zealand, we fell in love …

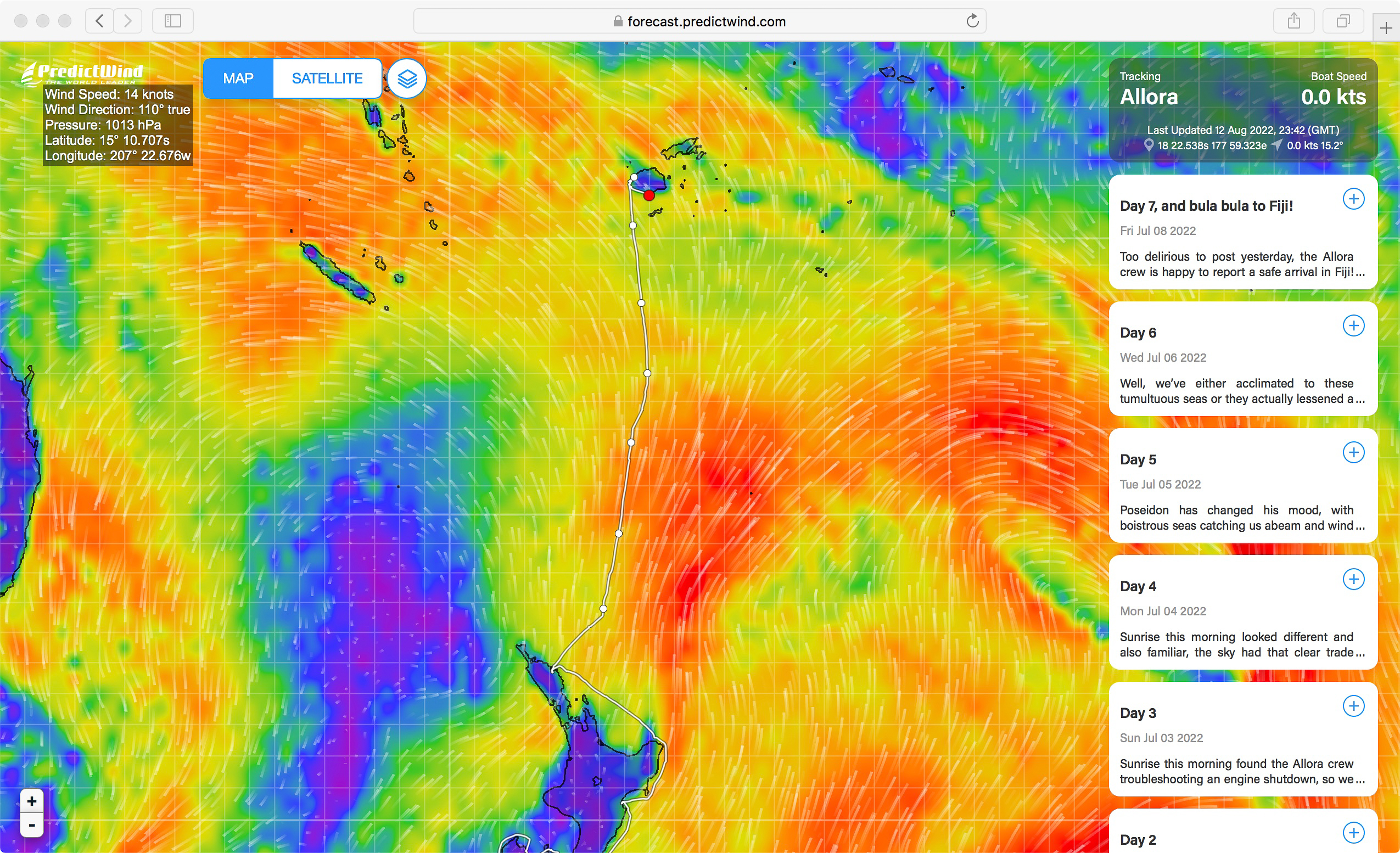

Passage to Fiji

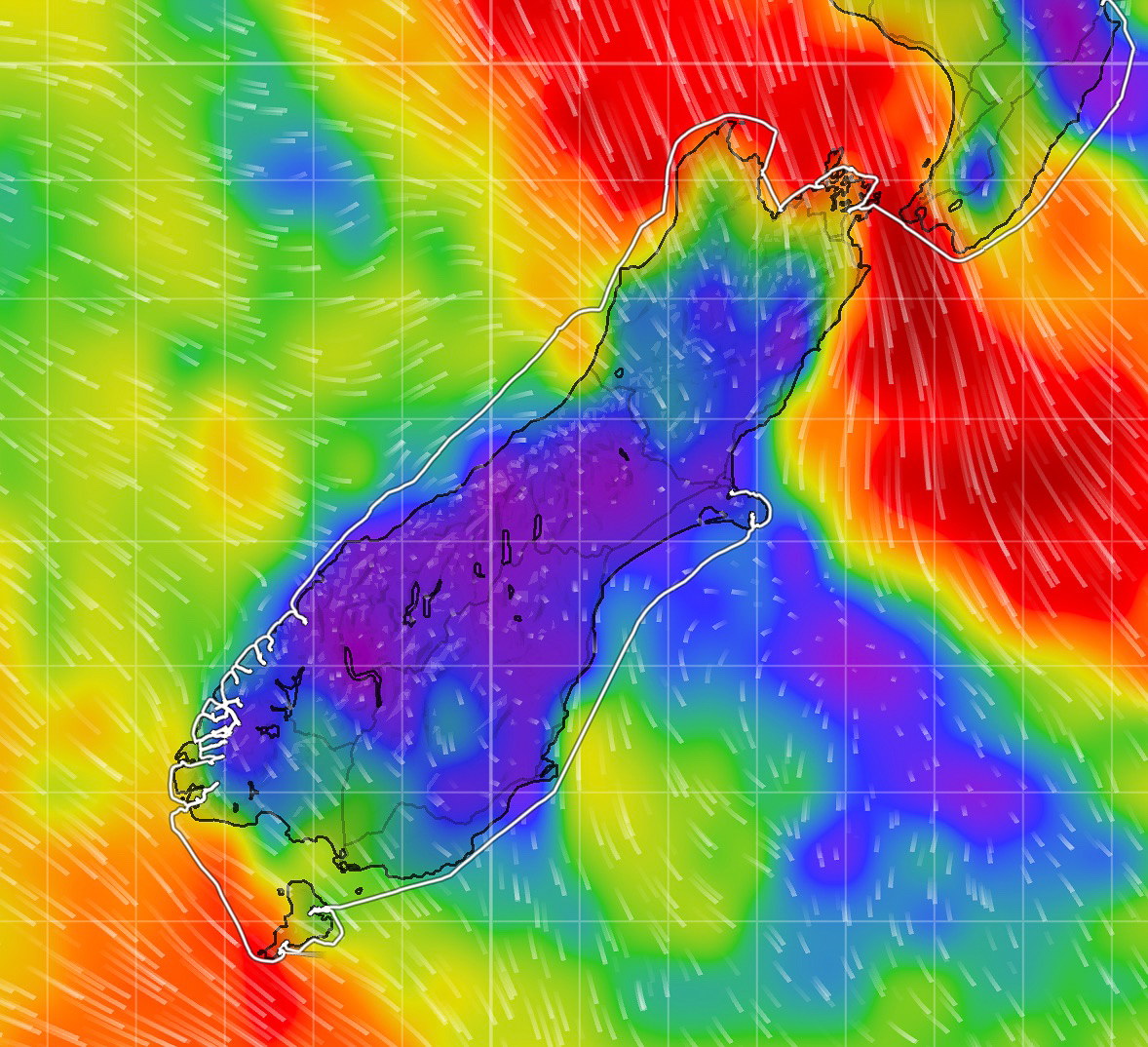

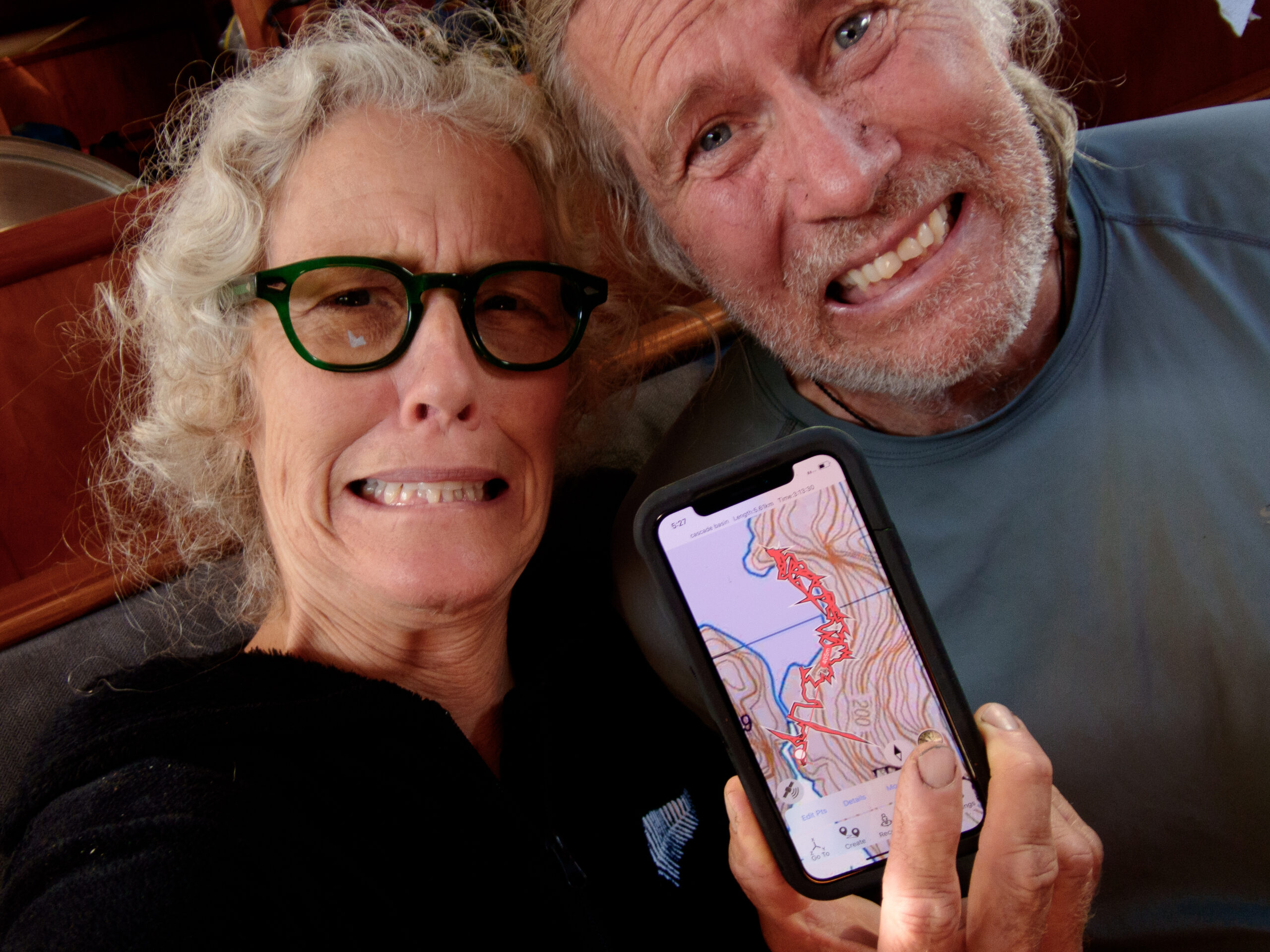

Words we used to describe this passage upon arrival in Fiji when asked by the manager of Vuda Marina (pronounced Vunda): boisterous, lively, bumpy, rambunctious. Our passage was probably pretty typical, as good as you could reasonably expect from Opua to Vuda Point, Fiji. We left on the very day our fourth consecutive visitor’s visa finally expired! New Zealand took such good care of us throughout Covid, but the time comes when even the most charming guests need to be encouraged to abandon the couch and find some new friends. We departed on the end of a passing front, which meant strong (up to 42kts) SW winds kicking us on the tail. Diana posted these notes via Iridium to our tracker.

“You would have thought we were eager to leave NZ – the way Allora shot out of the gate and rode the tail end of a ‘low’ with 3+ meter waves and up to 42kts of wind! We’re now 24 hours and 175 nautical miles in, and the seas are showing a trend toward easing with the wind. Currently on a port tack paralleling our rhumb line. The guitars have just come out and “I Can See Clearly Now!” Highlights: bioluminescence, Albatross, slightly warmer temps and Maddi as crew (just one night watch each, woohoo!”)

We hoped for maybe a day of wind to push us along, but we were lucky as the winds held out for almost two. You hear about the occasional passage with wind the whole way, but the horse latitudes aren’t called the horse latitudes for nothing… well actually there seem to be a quite a few theories about why they’re called the horse latitudes, only a couple of them to do with the paucity of wind. The basic idea is that this is where the easterly trade winds peter out, but is also the normal limit of frontal systems and westerlies in the mid-latitudes. Makes sense if the wind is going to switch from West to East that there should be some dead space between. We motored for just under twenty-four hours (we thought it might be as much as two days) using our 80 horses to get us through. We’re not big on running the engine (the noise gets tiresome and makes guitar playing tough), but we did enjoy the calmer seas, and the increasingly warmer night watches.

On my watch, just after dawn, just as I was about to shut the engine off and rally the troops to hoist the code zero, the engine made a loud screech and shut down without any warning beeps or anything. What followed was a gorgeous day of sailing in light beam winds with the big sail out that was a bit sullied by time spent trying to figure out what was going on with the engine. We suspected a transmission problem as there have been signs of impending doom for a little while, but we didn’t want make things worse and break something further, by trying to start it up until we could eliminate the possibility of water in the cylinders. I exchanged a few texts with the Yanmar guy in Lyttelton, Brian, who by good fortune happened to be at his shop on a Sunday, and he talked me through what to look for. Our mechanically minded sailor friends Ian in England (previously mentioned in this blog as the man with a plan) and Mark from Starlet both responded promptly to our SAT phone email with gearbox advice that was invaluable. I’m sure anyone can imagine how good it feels when you’re hundreds of miles out to sea, to have friends like this to turn to. Later, the Fijian mechanic showed us pictures of the main bearing in the gearbox which had literally blown up (which more than explained the problem.) Why is a longer story, which I’m happy to share with anyone interested in the gory details. I promise not to take the fifth. Luckily, we didn’t need the engine until well inside the reef at Fiji. By some miracle it held together long enough to get us into the marina.

The rest of the sail, the wind was on the beam or just ahead of the beam, consitently over 20 knots with 3 to 4 meter very confused seas for the first day, which slowly moderated a little (though the wind did not) and became more regular.

Maddi posted this note for Day 5:

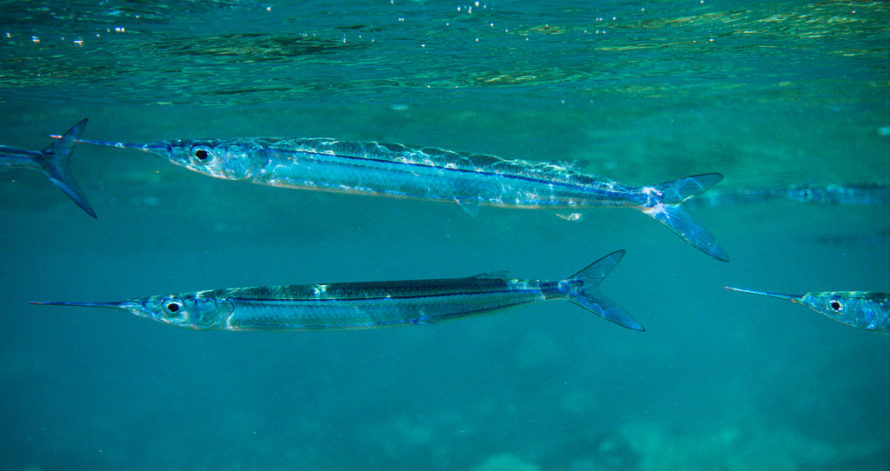

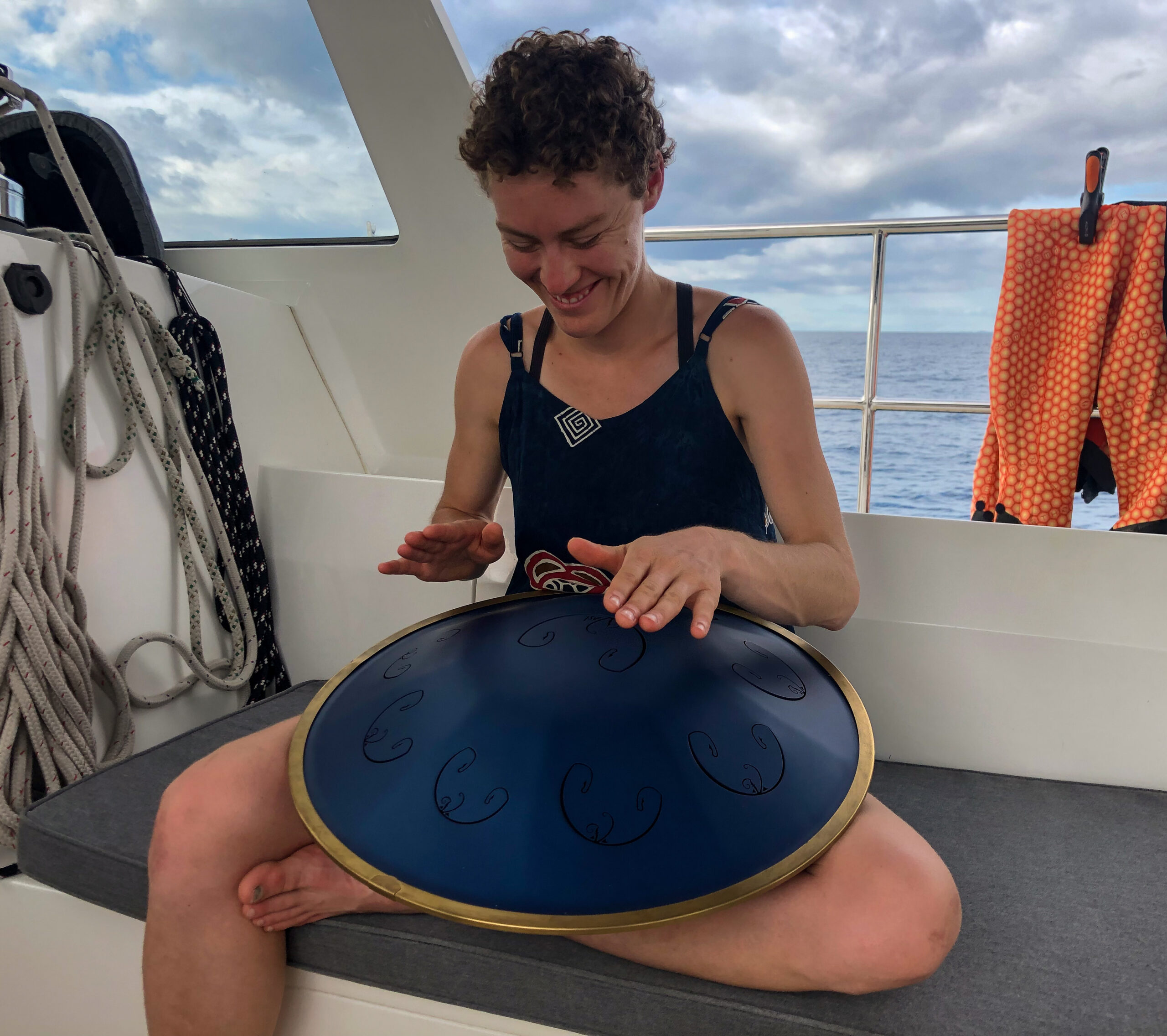

“Poseidon has changed his mood, with boistrous seas catching us abeam and wind aplenty. With our course now set for Nadi, the Allora crew has spent the day either laying down or holding on tight. It’s incredible how tasks that were easy in the weekend calm have now become ludicrously challenging: making coffee, putting on pants… just want to take a pee in peace? Good luck! We keep thinking things are calming down, but perhaps it’s just our imaginations (and wishful thinking from unsettled tummies). Allora, for her part, seems to bounce joyfully over the boisterous seas, carrying us northward. The warm air, puffy trade wind clouds, and occasional flying fish among the leaping waves remind us that we’re back the tropics. We managed to brave the splashy cockpit for some music today, and only one of us took a full dousing! Heading into the night a salty crew, with gratitude for the wind and hopes for mellower seas tomorrow.”

Though our speed through water was usually pretty stunning, it was all such a sloppy mess that our actual distance made good suffered. Still we logged a couple days over 170 miles, coming in at 7 days for the whole passage. After a rowdy, tumultuous, brisk and challenging ride, the calm water inside the lagoon felt surreal, the welcome song at the quarantine dock seriously touched our hearts and the Covid tests brought actual tears to our eyes!

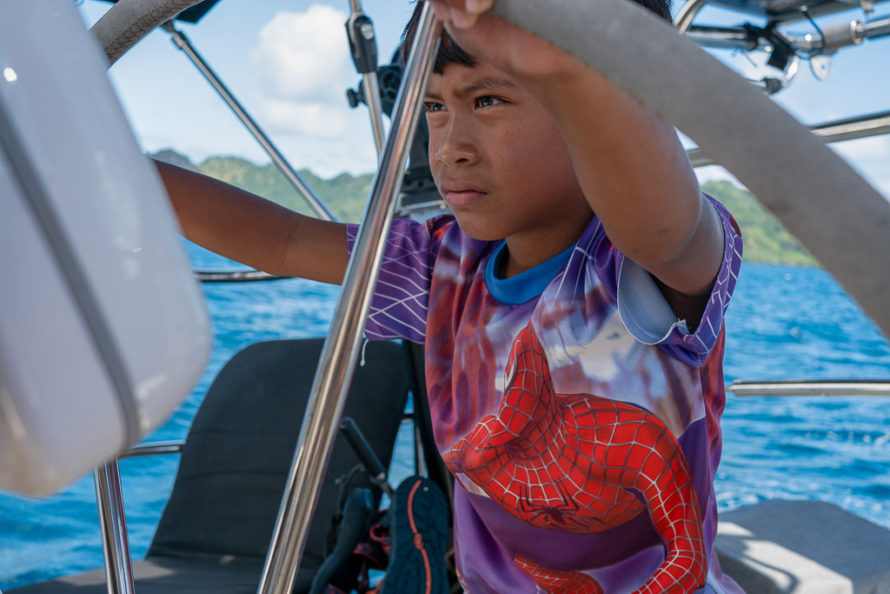

Maddi’s time in Fiji was already going to be pretty short, after waiting in Opua for weather, so we just couldn’t stand the idea of hanging out in the Marina, working engine or not, even though that would obviously be the prudent choice. We hadn’t seen the blown bearing yet, so blissfully ignorant, we decided that we would sail out to the reef for a couple of nights. We picked a spot that looked like we could sail onto anchor, and off, if we had to. Namo (our dinghy) was also standing by to push us along if all else failed. The wind cooperated (which is lucky because the engine quit again just after we got out of the marina and got our sail up), and though we didn’t have to sail onto anchor, we did have to manually drop it since the rough seas of passage had managed to drown a supposedly waterproof fuse box on the windlass.

The night before we had to take Maddi back for her flight, I woke up feeling pretty sick. Diana was feeling a bit off, too. She thought it was the rolly anchorage, I thought it might be bad food. By morning I was slammed. So Diana and Maddi brought Allora back without my help.

Unfortunately, there wasn’t a scrap of wind, so they motored the whole way, with Diana in deep psychic communication with the Yanmar 4JH80, to keep it together until she could get all the way in the narrow marina entrance and tied up to the circular quay at Vuda. I watched from below – first the palms of the channel drifting by and then our neighbors’ masts as she wedged Allora into her spot, bumper to bumper with boats on either side. Flawlessly executed. We realize we really need to trade jobs now and then, just to practice for occasions like this. ~MS

Passagemaking: Milford Sound to Abel Tasman National Park, South Island/NZ

It was a bit spooky sailing out of Milford at midnight without a moon. We had our inbound tracks on the chartplotter to follow, but it’s pretty amazing how disorienting darkness can be, even for feeling whether to turn to port or starboard to follow a line. Also with the steep granite walls, we didn’t feel 100% confident in our GPS. Diana went to the bow, and I stepped away from the helm to try to orient myself every few minutes, as we moved cautiously down the fiord. Though the GPS did seem to have a decent idea about where we were, it was also reassuring to have radar confirming the distance to the rock walls on either side. But what helped me relax most at the helm, was when Diana shouted that the dolphins had come to escort us out. I leaned over the rail and could just see and hear them splashing off our port headed for the bow. It was hard not to feel like they’d showed up intentionally to reassure us.

One of the many challenges of the passage from Milford up around Cape Farewell into the Cook Strait, is that there is only one place you might possibly stop, but that requires negotiating a river bar entrance at Westport (just north of Cape Foulwind!), which is safe only in decent weather. Otherwise, it’s a solid three day run (if you keep your speed up), which just barely fits into the cycle of weather shifting from South to North. The weather window that presented itself to us seemed pretty typical, catching the end of a southerly, motoring and motor-sailing through variable winds in a race to meet the Cape with relatively light winds rather than the usual NW or SE gale.Leaving sooner, we’d have had more wind to sail with, but we’d risk arriving too early for the switch of winds at Cape Farewell.

Diana took the first watch just after 2 AM after we cleared the hazards on the north side of the entrance to Milford and could head more directly north. “Really cold, icy hands,” she wrote in the margins of the logbook. “Overcast skies heading further out to clear Arawua Point/Big Bay Bluff.” Just after sunrise on my watch, I got a glimpse of the mountains south of Mt Aspiring, which reminded me of Wyatt’s 100 mile run the length Aspiring National Park. I wondered if he could have seen the Tasman Sea from any of those lofty ridge lines he traversed?

Also in the logbook, I see a lot of scribbles in these notes about fuel rates, and estimates of actual fuel burned for miles ‘made good.’ Allora carries 190 gallons full which is more than enough for the distance as long as the weather is reasonably cooperative, but it makes a difference if you’re burning 1.5 gallons/hour or pushing the engine and burning 2.5 gallons/hour. The extra gallon doesn’t double your speed. People better at the maths would probably be able to calculate exactly what fuel rate is most efficient. I settled upon 1.6 or 1.7 as an nice compromise of efficiency, speed (to make our date at Cape Farewell) and comfort.

We had rain. We had current steadily set against us. We had dolphins streak by in the night leaving comet trails in the bioluminescence. We fussed about the wind, almost-but-not-quite-enough to sail, ever creeping up on the nose. We almost lost a batten in the mainsail. Then later, Otto, our autopilot made a sudden decision to turn hard to starboard out of nowhere. The switch for the high pressure pump on the watermaker heated up and set off the smoke alarm (naturally at night-while I was off watch). We saw no other boats besides the occasional fishing boat working closer to shore. We caught a glimpse of Aoraki (Mt Cook) at sunset, and at Cape Foulwind a couple of seal lions waved as we passed by.

On the last night, as seems to be a theme lately, Diana drew the toughest watch of the passage. There was just no way to completely avoid a patch of heavy winds slated to meet us as we approached the Cape, straight on the nose. We tried to time it for the least possible, but Poseidon wasn’t going to let us off feeling too clever. For her whole watch, Allora slammed into 20 knots on the bow clawing her way up the last bit of coast to Cape Farewell. Finally, after calling Farewell Maritime radio to try to find out whether it was generally considered advisable to cut the corner at Kahurangi shoals (which they weren’t really able to commit to), we decided it probably wasn’t, so we slogged on. Diana went off watch and very soon after, we were able to fall off the wind. Just five degrees made a big difference. Pretty soon we were motor-sailing and by Diana’s last sunrise watch she was able to shut the engine off and sail along Farewell Spit, an amazing 25km sandbank off the northwestern corner of the South Island at the opening of Cook Strait. The winds were light but sweet. Finally! ~MS

Magical Milford Sound/Piopiotahi! – Fiordland

Piopiotahi (Milford Sound) resonates with awe and leaves us speechless, like the Grand Canyon or Machu Picchu, or the Magellanic Clouds on a vividly starry night at sea. The sheer mass and scale, the soaring beauty, each breathtaking turn. Words just pour out, but fail to capture what it feels like to sail into this magnificent fiord. The day we spent in this unique-in-the world place, was blue and lit with sun, the water impenetrably deep, granite walls towered over us, beyond imagination and comprehension, the waterfalls gushed bountifully without end. Apparently Captain Cook missed Milford on his first pass, and actually that’s not entirely surprising. Approaching from the sea the fiord begins rather humbly and then builds and builds in its symphonic crescendo of magnificence. A bit much? Not really. Every time I stepped away from the helm and out from under the dodger I caught my breath as I looked up and up. ~MS

George Sound/Te Hou Hou, (‘Georgious!’) – Fiordland

The run outside between Caswell and George Sounds is around 14 miles. We left early to try to beat some forecast rain and gusty NW winds, and almost made it. The rain started just as we made our turn in. Diana logged the max wind at 27.2 knots, then went down and crossed it out to a revised 29 knots. By the time the wind had blasted us another two miles down the sound, Diana had crossed that out to record 42 knots. Looking on the chart with the wind howling behind us, we were concerned if Anchorage Cove would be able to offer any shelter from this angle of wind, even though it’s listed as an ‘all-weather anchorage.’ We worried it might be too gusty to safely negotiate the narrow spot between the river bar and small rocky island. We decided to poke in and check it out if we could. Right away the wind dropped into the low twenties then the teens, which still felt like a lot to try getting into the tight spot where fishermen had set up a line we could theoretically side tie to. The rain hammered down as Diana watched from the bow for shallow rocks off the island and I maneuvered Allora in, ready to back out if we needed. Despite whitecaps just outside, the winds this close to the little island dropped to near zero and Allora was able to hover effortlessly while Diana (in the kayak) quickly tied lines on the bow and stern, getting absolutely soaked in the process. It was a kind of a crazy feeling, the sudden stillness and security of that spot with gusts in the forties not half a mile away. We wouldn’t have guessed even from a couple hundred yards out that it was worth chancing. ~MS

Northward to Charles/Taiporoporo Sound, Mesmerizing – Fiordland

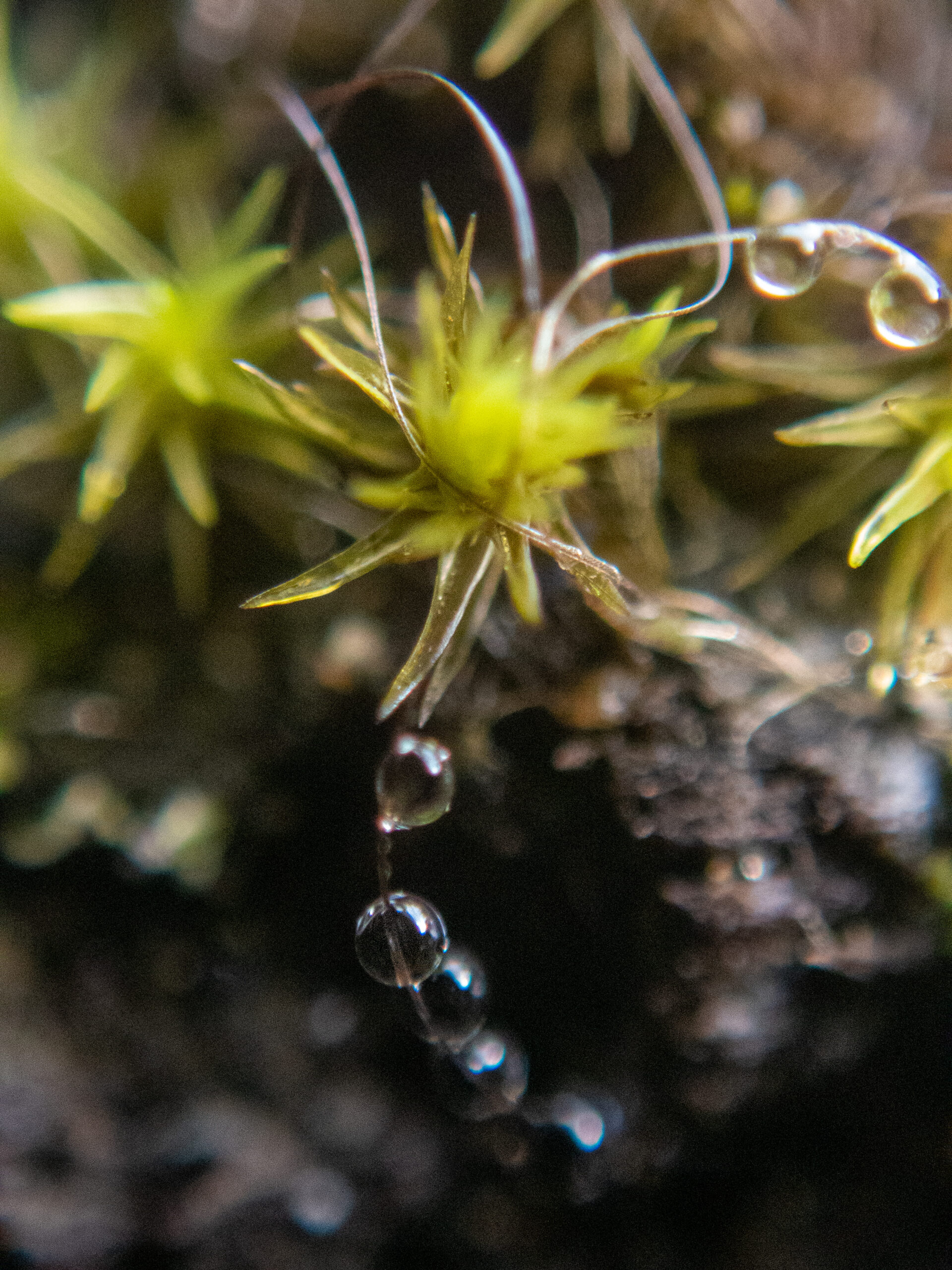

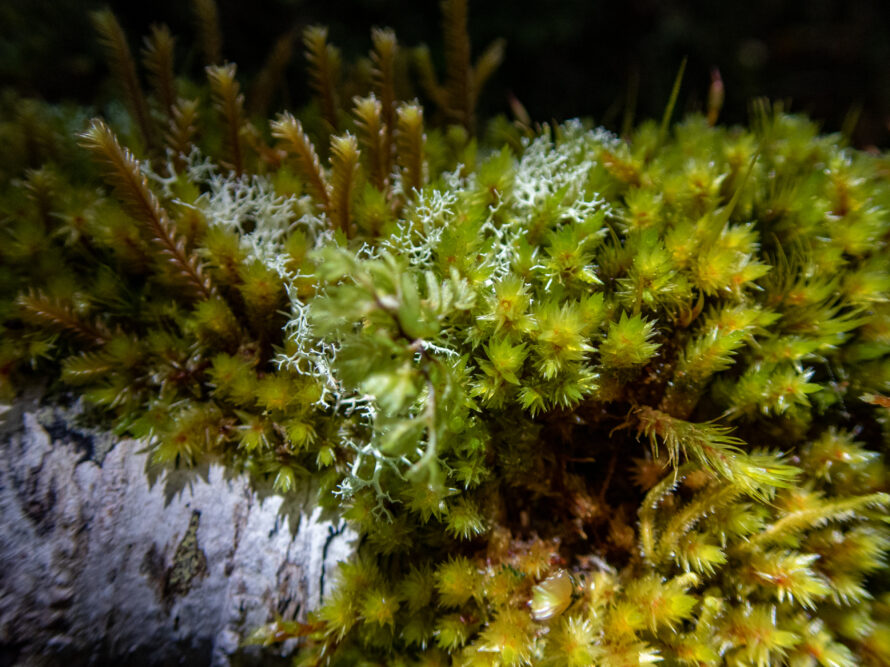

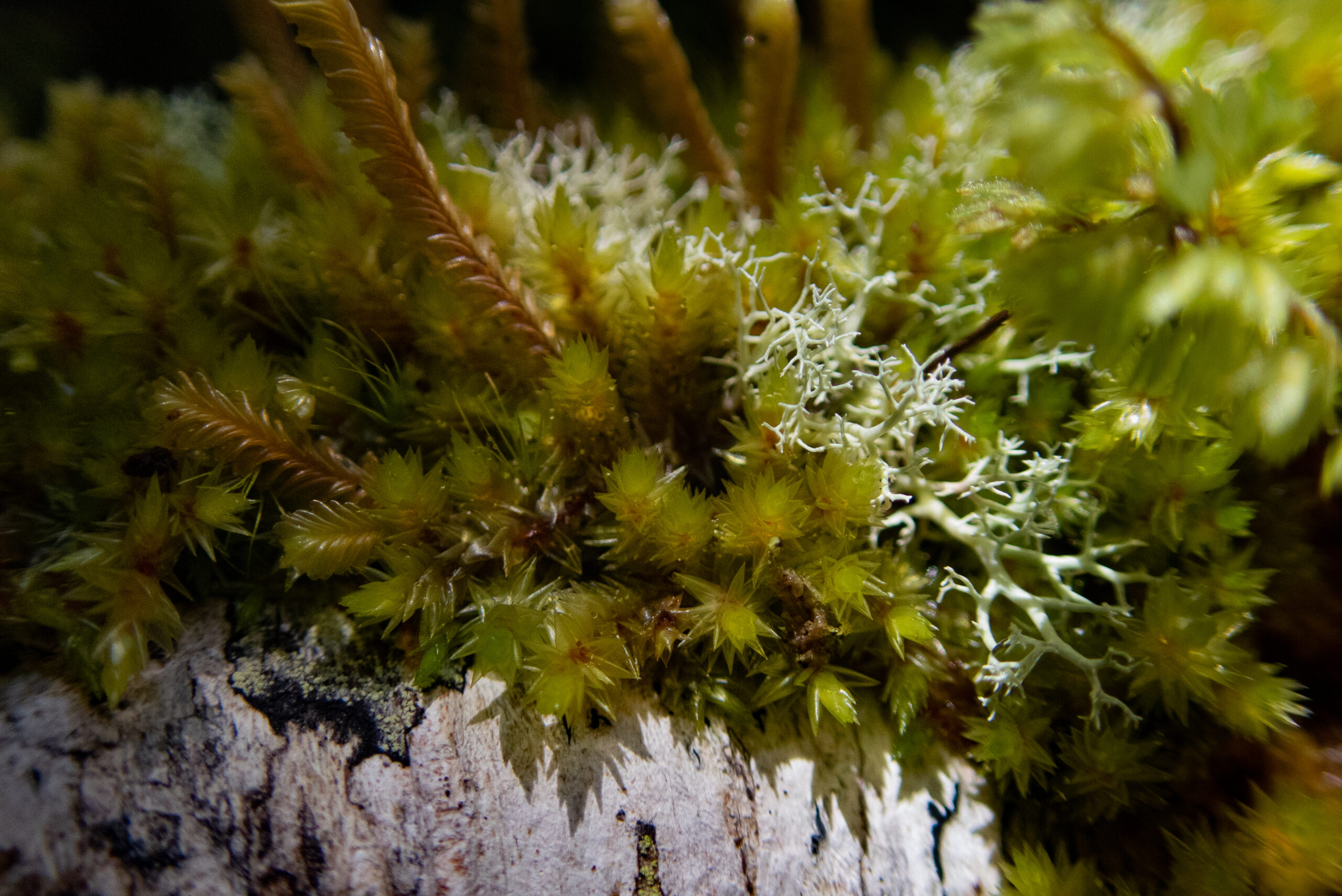

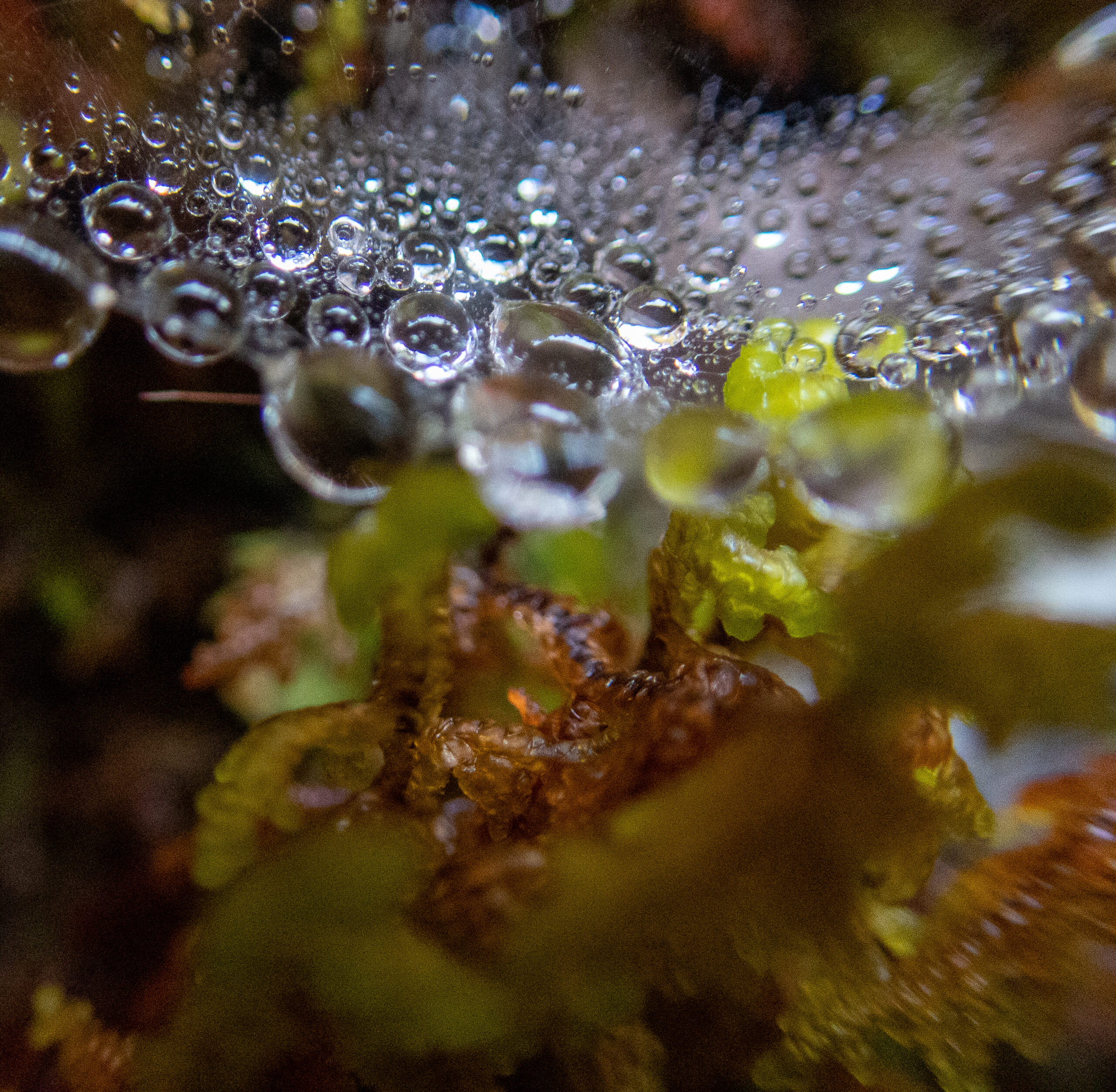

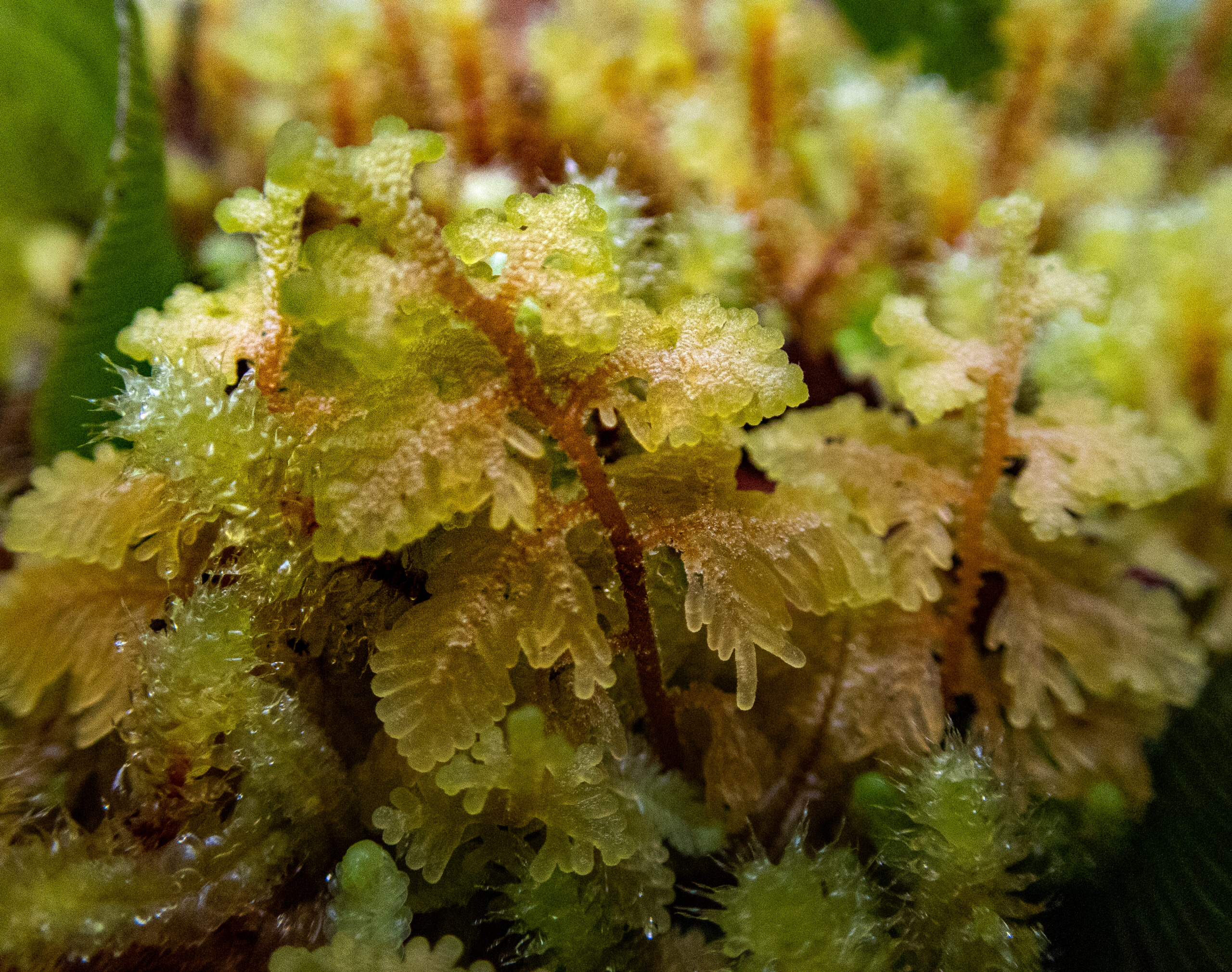

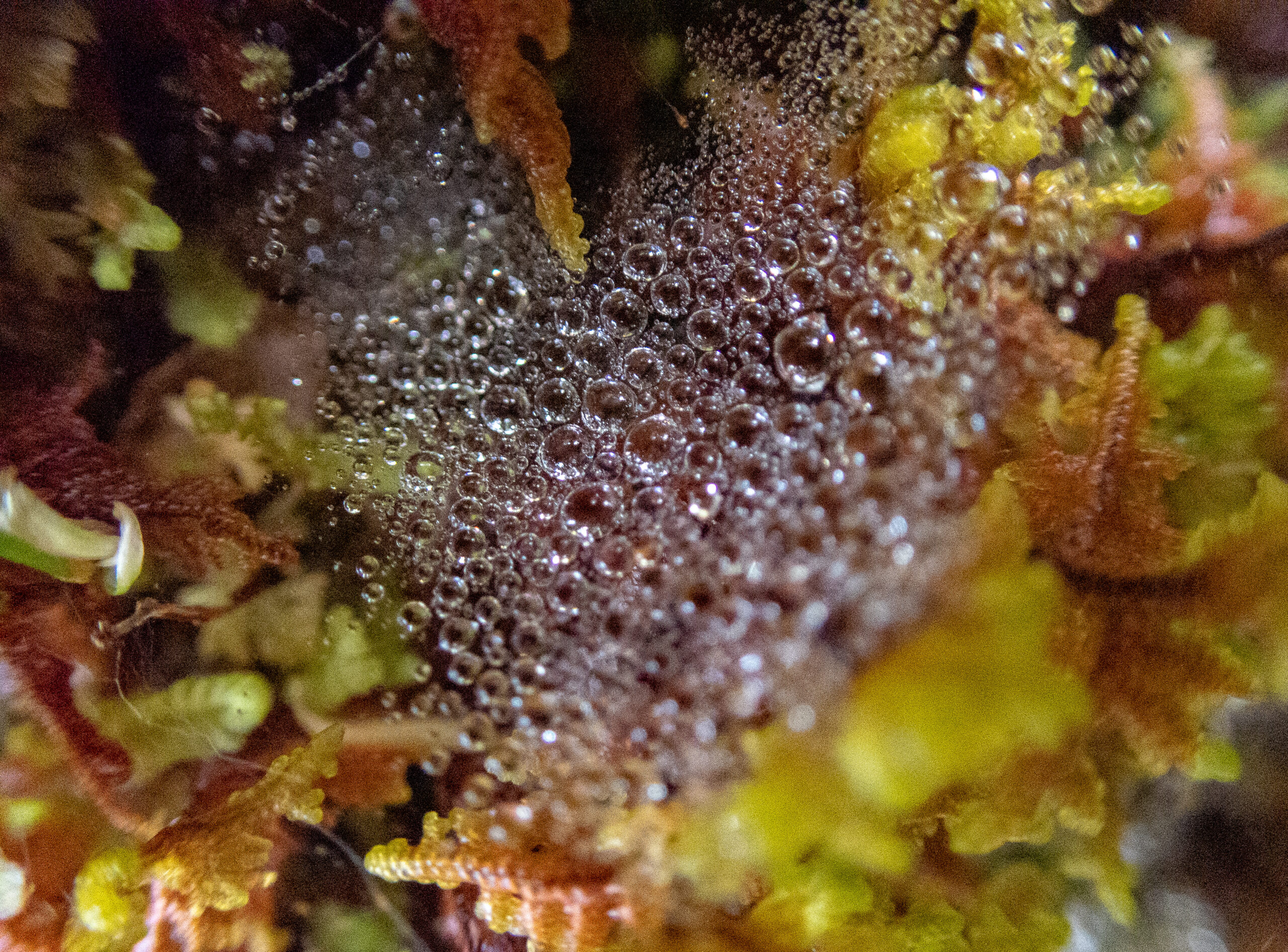

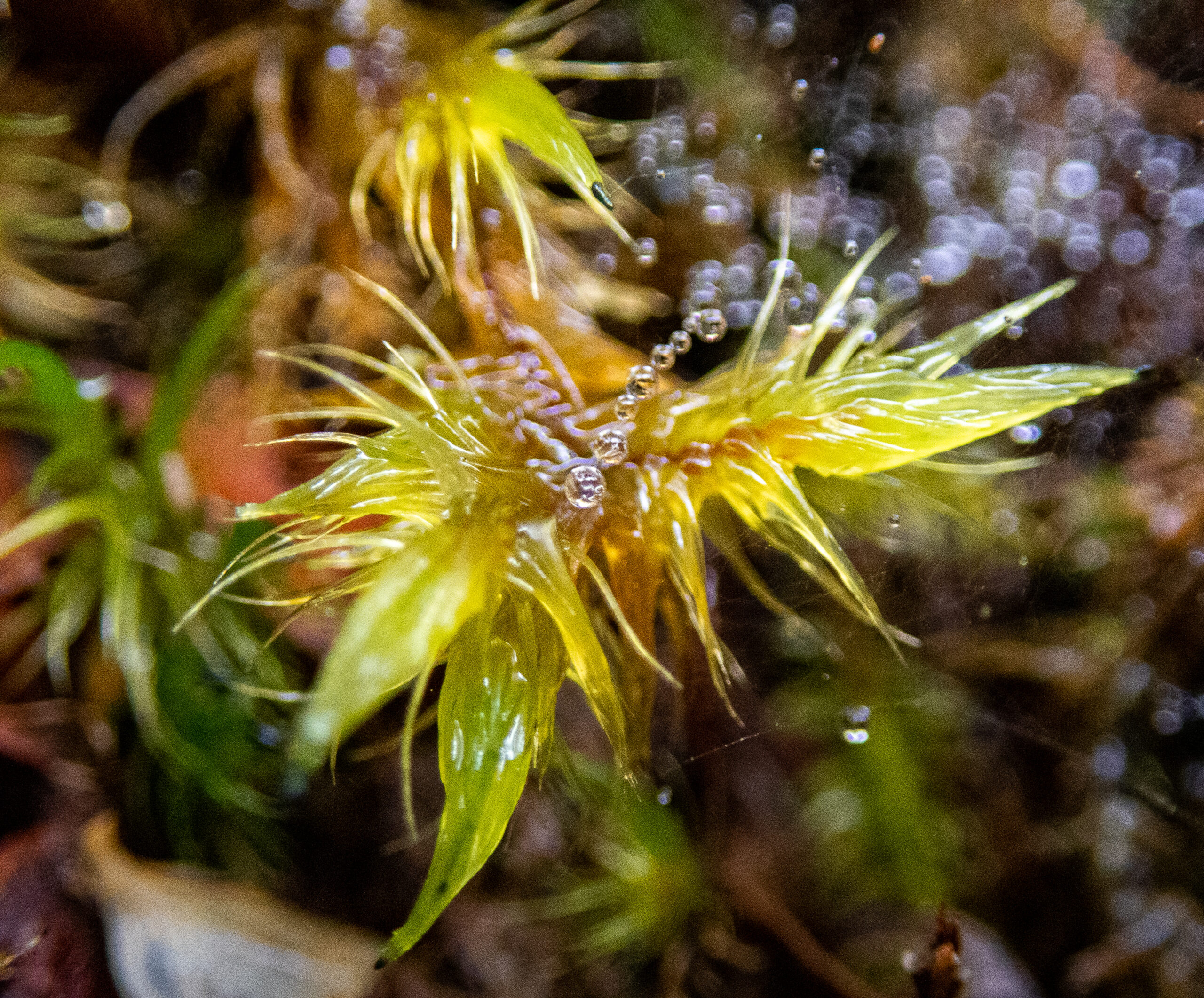

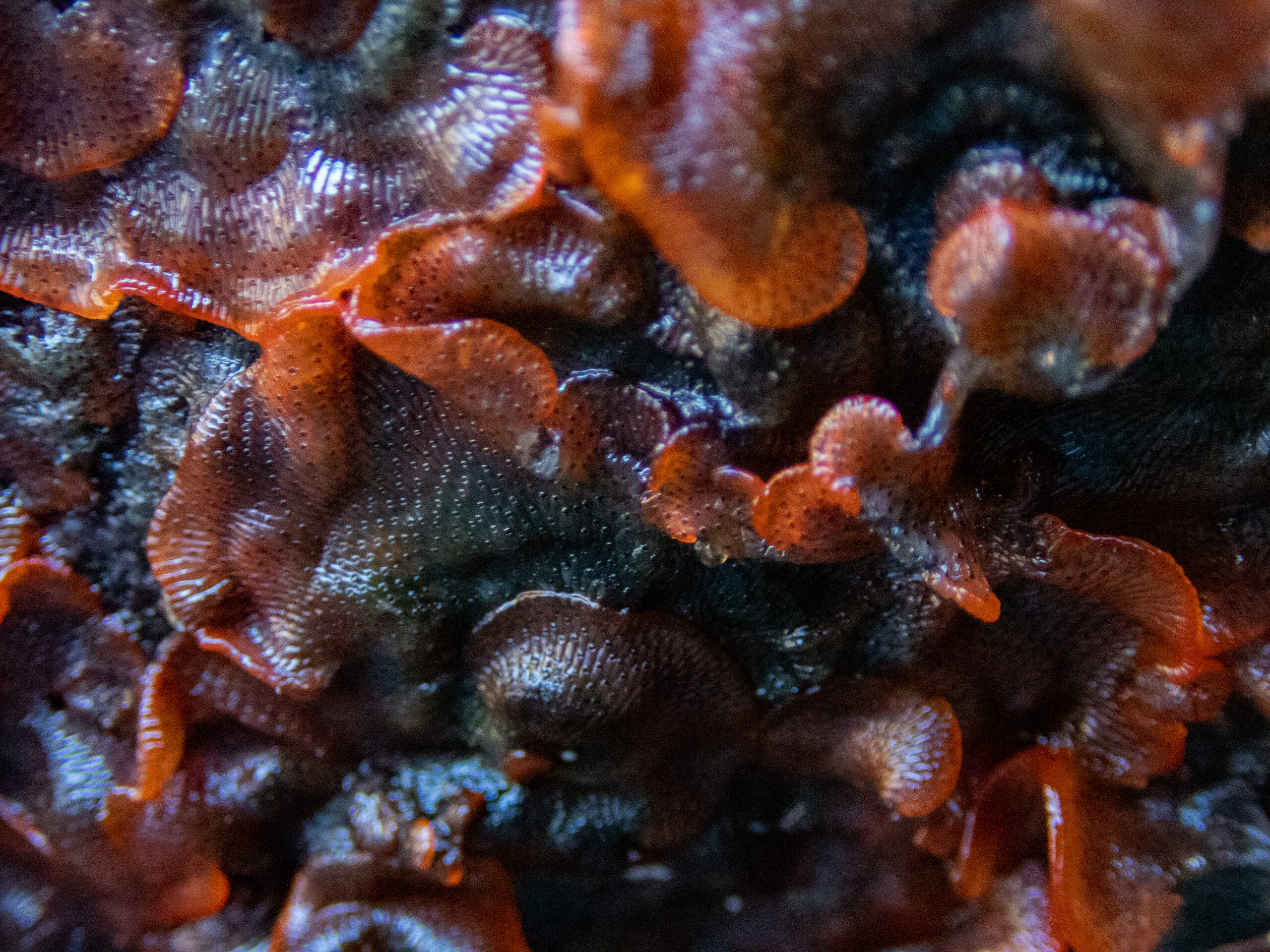

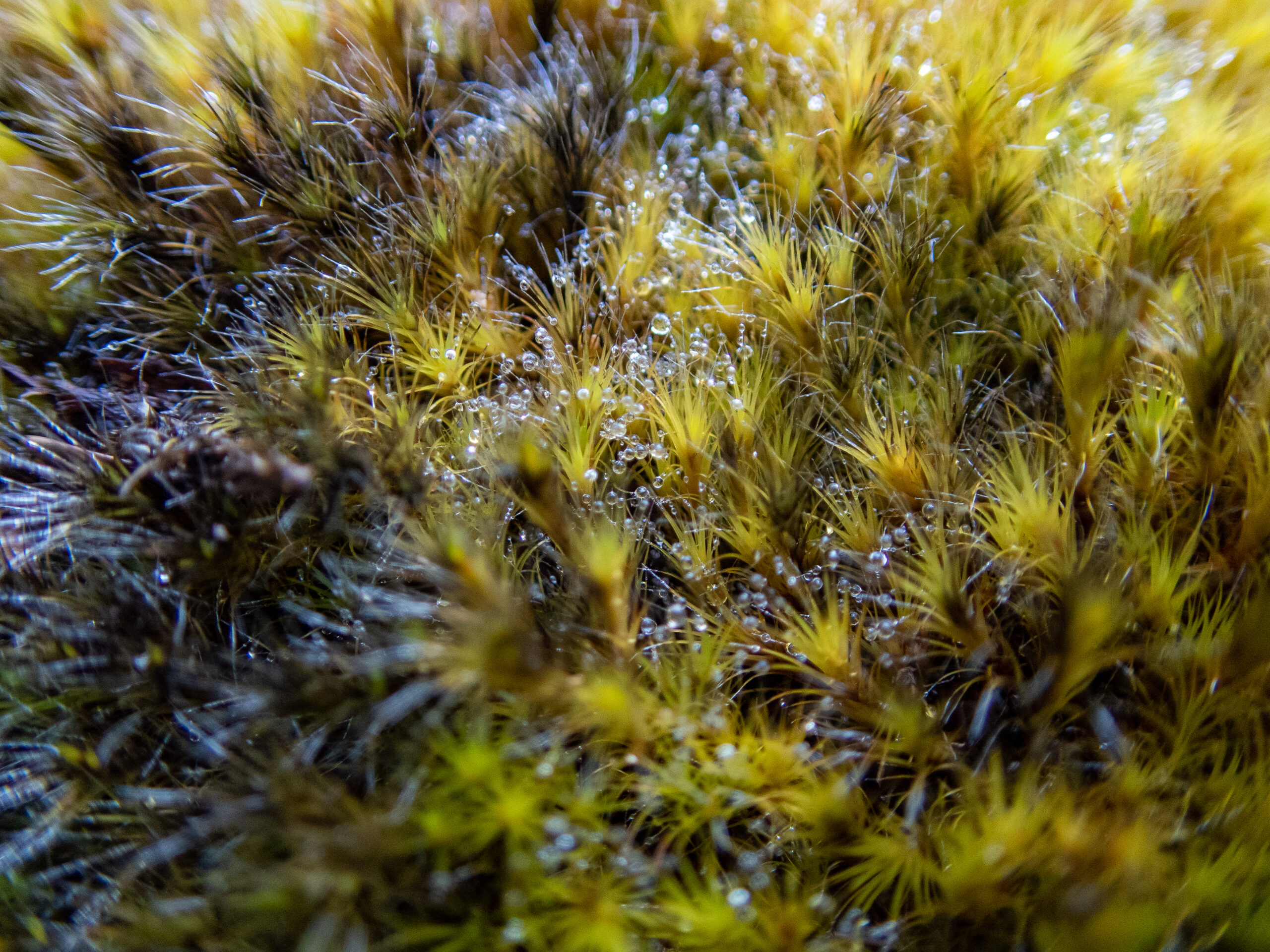

Abstracts

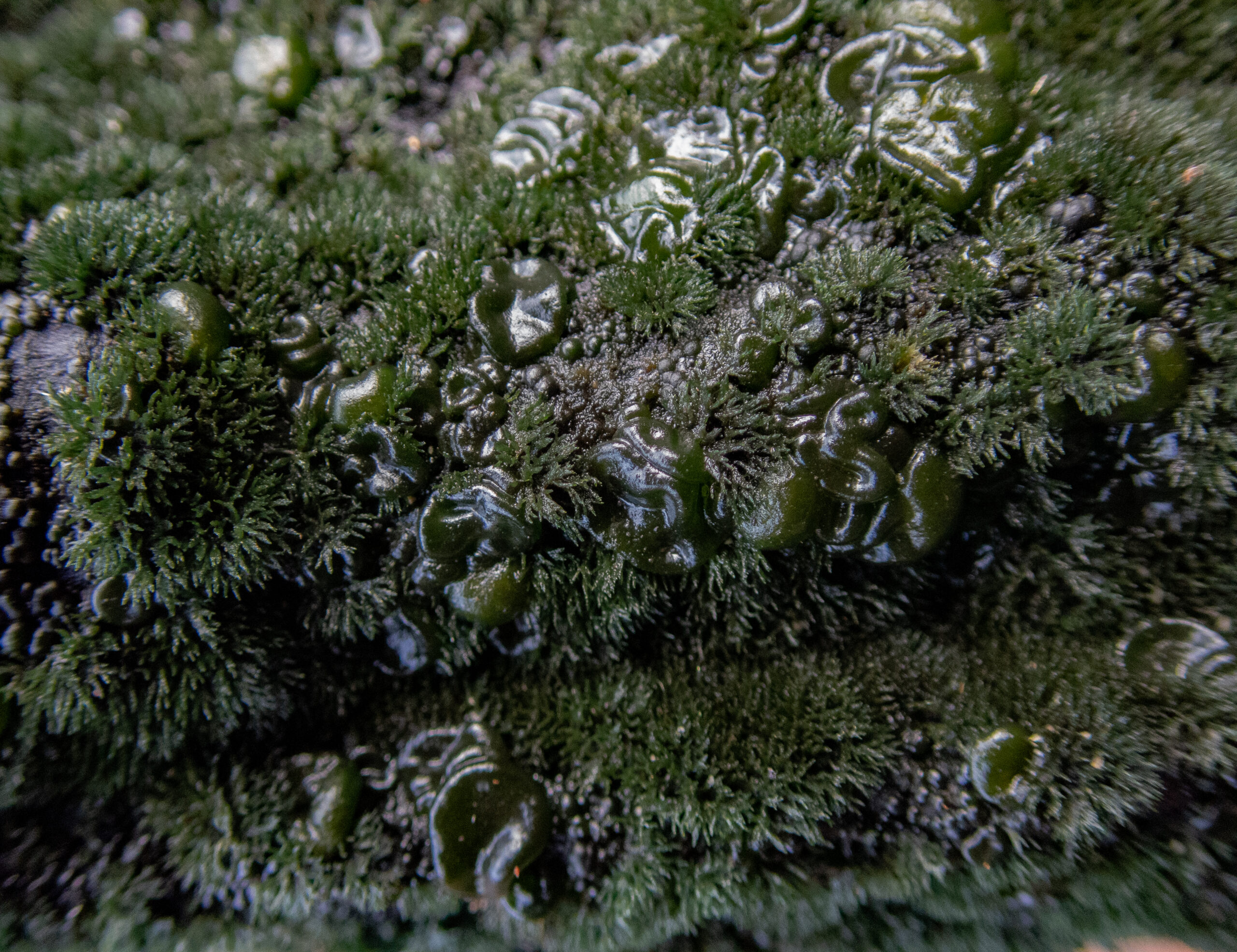

My favorite of Diana’s photographs from Fiordland are the “abstracts,” which she discovers by looking in a very careful, unique way, at the tidal line along the rocks, that magical transitional space between the hidden world underwater and the green, vibrant life-on-fire world above. Bare stone, stained and painted with time and color, bent and reflected by the still, secret, freshwater shimmering over the tide, the infinite, creative capacity of nature. Diana uses framing to share this vision, to point out Nature’s mastery of abstract art. It’s no surprise (and no accident) that these images feel so profoundly connected to her mosaic work. Most of the time these photographic expeditions are her solo meditations, which she shares with me when she gets back to Allora (after hours in the kayak!). But I’ve also been with her, paddling Namo gently into position, sitting right next to her, appreciating the wholeness of a beautiful place but without quite seeing what she is seeing. These images, for me, represent a particular (and particularly magical) collaboration between Diana and this very, very special world we are navigating in Fiordland.~MS

Dagg/Te Ra Sound, shared only with Wapiti in the ‘roar.’ – Fiordland

‘Anchorage Arm’ and had glassy calm conditions. Instead of trying to find shallow enough depths in the middle to anchor in, we snugged up super close to shore utilizing some fishermen’s lines which are rigged in place. Wonderful protection from winds, mellifluous creek sounds and voracious sandflies!

Something happened when the twenty North American Wapiti Roosevelt gifted to New Zealand in 1905 found their way into the heart of Fiordland’s steep and impenetrable wilderness. Maybe there’s a perfectly rational scientific explanation (maybe it has something to do with crossing breeding with Red Deer?). They got a bit smaller than the fat and happy elk of Yellowstone (which certainly makes good sense given the dense rainforest) but they also changed their tune, no longer bugling with that iconic, haunting call that resonates across the frosty parklands, lodgepole forests and granite peaks of the Rockies. Our visit to Daag coincided with height of the “roar.” It’s a sound that does not “belong,” but also feels so fitting, as though giving voice to the thick ferny jungle of that unpeopled wilderness. Deep, guttural, plaintive and haunting (in their own way) – their roars echo across the still water and ridiculously precipitous canyon walls. You can hear individual stags make their way up and down the steep shore, and we paddled Namo as stealthily as we could manage along the shore hoping for a glimpse, and though they often seemed very close, we never saw them. We could only imagine their antlered heads tilted back, belly’s trembling as they gave voice to the wilderness.~MS

Although Spanish moss grows on trees, it is not a parasite. It doesn’t put down roots in the tree it grows on, nor does it take nutrients from it. The plant thrives on rain and fog, sunlight, and airborne or waterborne dust and debris.

Known for it’s friendly, ‘cheet cheet’ call and it’s crazy flying antics, the Fantail or Pīwakawaka often follows another animal (and people) to capture insects. Time and time again, though, they acted as guides; when we were off track in the woods, they’d appear, chirping energetically, as if to say, ‘no … not that way, THIS way!!’ I learned to always follow them!

Some fungi fun: I haven’t had the time to research ID’s on most of these, so write me if you know and are keen to share?!

Vancouver Arm: Head of Bay, Third Cove, Stevens Cove, Breaksea/Te Puaitaha Sound – Fiordland.

Broughton Arm, Breaksea/Te Puaitaha Sound, Captivating! – Fiordland.

We were primed to love Broughton Arm. Tony, a New Zealand sailor we met in Tonga (from an Auckland sailboat building family) got there ahead of us and posted his impression, the humbling sense of privilege he felt to be in the remote presence of such mighty granite walls and peaks. “Paradise found!,” he exclaimed. It’s hard to think of a way to convey the heart sense of moving through pristine and unpeopled areas like this, the sense that goes beyond the imagery, the waterfalls, and magnificent trees, the wildlife. The sense of living stone and water and place. You look at one of the these peaks soaring above the the fiord continually stunned by the mass and energy represented there, and then by the bounty of life exuberantly, vividly greening those granite flanks. And water, water, water everywhere. ~MS

Wet Jacket Arm, not just any Arm – Fiordland.

Lots to captivate ~ lingering rainbows, new waterfalls, breathtaking bush, dolphins and surreal reflections while moving up to the end of Wet Jacket Arm. I wrote these words in the logbook from that day: ‘OH MY GOODNESS – A VISUAL FEAST!’

Mountains and Waterfalls and Reflections, oh my! Preservation Inlet/Rakituma – FIORDLAND,

Last Cove, Preservation Inlet

My first series of thoughts were about the precariousness of our situation, and how much we depend on our engine, despite being a sailboat. What in the world would Captain Cook do? We had arrived at the entrance to Preservation Inlet a couple of hours too early, despite our attempts to slow Allora down. No wind but a big southwest swell colliding with a northerly chop was making going slow under power uncomfortable, the mainsail slatting back and forth despite the preventer. We had already decided to edge up toward Dusky Sound (another twenty miles onward) and go in there instead as long as the forecast northerly held off. I’d barely turned Allora in that direction when the wind began building, directly on our nose, gusting up to 16 knots. No harm in poking a little further that way, to kill time. The Puysegur lighthouse flashed bright and high on our beam, a reminder of where in the world’s oceans we were. Puysegur hosts gale winds or stronger 300 days a year. The weather models showed the next gale arriving by afternoon, by which time we needed to be safely tied up at anchor. The first issue with the engine I noticed was that the display at the nav station was off. Weird, I thought. Then I noticed the gauges in the cockpit, shutting off and popping back on. Very weird. Then the engine warning came on, beeping insistently. What the heck? Thinking mainly at this point of not waking Diana who’d had a very rough night already struggling to get to sleep for the first few hours of my watch, I quickly shut the engine down. Then as we slowed in the airless swell, I pushed the button to start it back up. It flashed and went off. I tried again, it stayed on long enough for me to get a couple slow, battery dead, rolls of the engine. I had been thinking it was time to replace this starter battery, in fact, I had just had a conversation with Willy on Pazzo about how you know when your starter battery is dead. I should have known better than to bring this up with him, since the last boat conversation I’d had with him was about our flawless autopilot, which literally failed the next day (the first time in six and half years). For a few panicked moments I couldn’t think about anything except the weather forecasts I’d been looking at that predicted wind on the nose if you tried to sail for Dusky and no wind at Puysegur until the arrival of the gale. I guess Captain Cook would just have had to sit there roll in the three meter swell and wait for however many hours it was going to be until the gale chased him in. I didn’t like the sound of that at all. I went below and switched the starter battery to combine with the house batteries and the engine started up. Phew! But the engine warning was still blaring CHCK ENGINE. Amazingly, Diana was still sound asleep, despite about the blaring warning lights, or me running up and down the companionway, starting and stopping the engine. Okay, I checked the oil. I checked the temperature. I checked the cooling system. I checked the transmission. All good. The engine sounded absolutely fine. I’d installed the display at the Nav because supposedly it might give me more information than just CHCK ENGINE… how about check battery, or check electrical system? I reluctantly woke up Diana to tell her about the situation. It definitely did not seem like a good idea to head toward Dusky, we agreed. I figured out how to make the engine warning beep a little bit quieter below and she tried to get back to sleep. I started a slow zig zag toward Puysegur lighthouse, chugging along at under 3 knots, keeping a wary eye on the churning cauldron of Balleny Breaks less than a mile northeast of us and slowly got used to the steady ringing of the engine warning. We motored up the stunning Preservation Inlet to Last Cove as I kicked myself for ignoring my instinct to replace that starter battery. I’d checked it and it seemed okay, but it would have been relatively cheap and easy to replace it, just in case, and not be in this situation. Our first anchorage in Fiordland. We’ve been working on how to set our anchor and lines, a sleepless night from the passage and an engine with a steady CHCK ENGINE still blaring did not make it easier. With a big blow coming we wanted to get it right. 300 feet of rode and two lines to shore.

The weather models, all four that we download via satellite, predicted this narrow window for rounding the great cape on Stewart Island and sailing with an easterly breeze up to the notorious Puysegur before the wind switched northerly with forecast 50+ knot gusts. We put a lot of faith in them, and they were spot on. After a long nap, I started the project of dealing with the starter battery. My idea was to replace it with one of the house batteries. In the process, I had the thought to check the Duo Charger which regulates the battery charging from the engine’s alternators. The installation showed two fuses and as I pulled the wires to find the inline fuse, I noticed the one for the starter battery was a bit loose. I tightened it up, started the engine, and the charging voltage jumped up right to where it belonged. A loose wire. That was all. Three turns of a screw. ~MS

Cascade Cove, Preservation Inlet

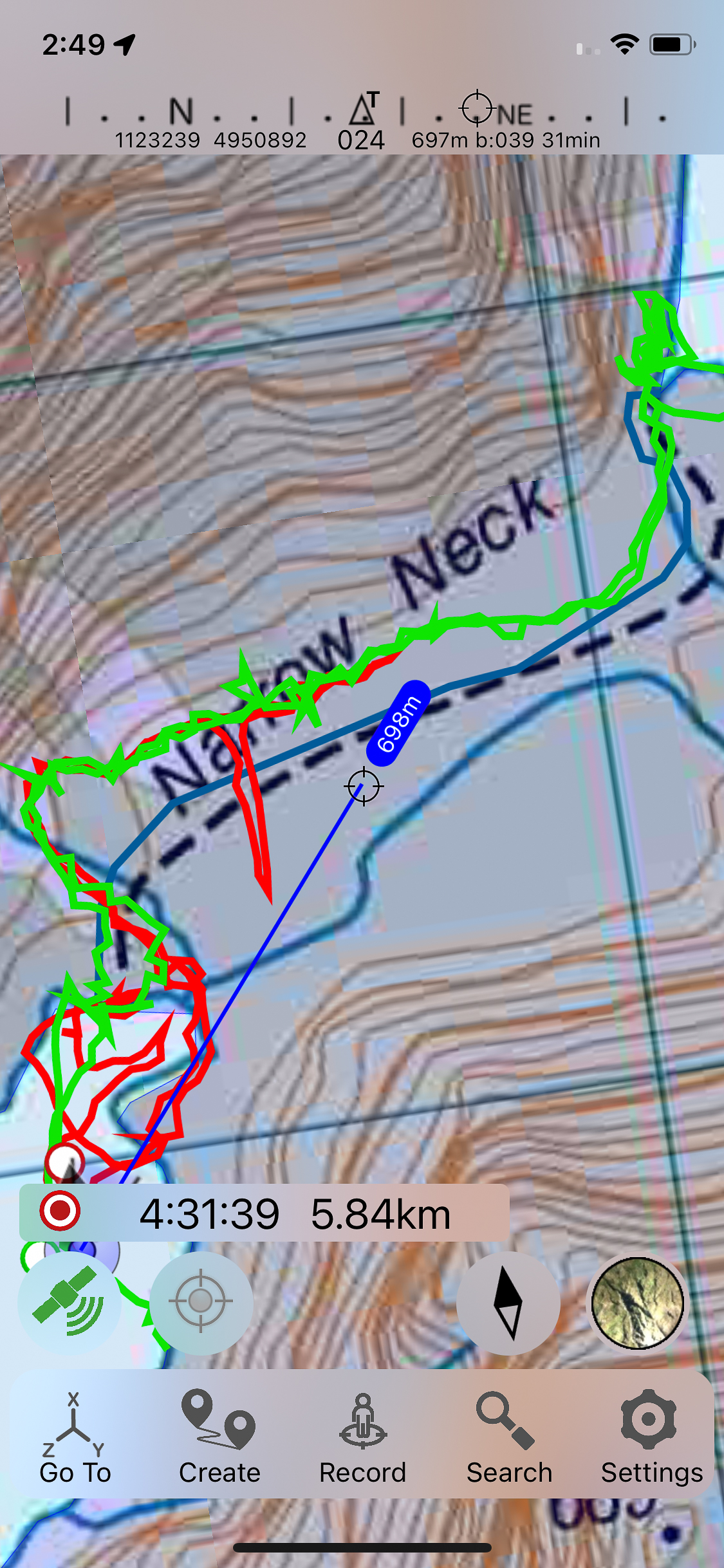

We arrived as the announcement came over the PA on a small Real Adventures cruise boat anchored at dead center in the cove, “the generator will be turned off at 9:30 and then back on again at 6:00 for your convenience…” Two crew walked to the bow, short sleeved black uniforms and to our delight, weighed anchor, the boat disappeared past the head of the cove and left us to the cheerful sound of a small waterfall pouring down the rocks next to a stout blue shoreline. We dropped our own anchor and tied up a boat length from shore. One of our books said that brown trout inhabit the river which flows into the lake above the dramatic falls at the head of the cove. A mere two kilometers as the Tui flies. All we needed to do is scramble up the side of the falls, then bushwack along the lakeshore. We clambered up, relying on roots and branches for hand holds, worrying about the way back down, and somehow made it to the top of the falls. The steep sided outlet of the lake forced us up and up over fallen mossy logs and broken rock faces. Every step was a miniature triumph as we inched and wiggled and scooted minutely closer. The edge of the lake, walking in the shallow was better for a while, until it became a mote of surprise waist deep holes and fallen logs. After hours invested in about a kilometer of progress, we admitted defeat and turned back, now knowing what lay ahead. Many times we expressed gratitude for the near absence of sandflies and the forest herself was pure magic of green mosses and deep ferns and wise old trees. Back at the outlet of the lake where for a brief time there had been trail flags to follow, we found a row boat pulled ashore that we had walked right by. Those Long River brown trout will never know how close them came. The biggest challenge was finding our way back down to the dinghy tied up in the outflow below the falls. We had cleverly laid out markings with sticks on our way up to mark the way, but those didn’t work out any better than bread crumbs did for Hansel and Gretel. We cliffed out, over and over again, but eventually, banged, bruised and muddy found a way down, never more happy to find Namo, dutifully waiting to take us home.

Next stop: Fiordland/Dusky Sound

Port Pegasus, Pikihatiti, southernmost region of Rakiura/Stewart Island

Port Pegasus

After a long period in the 19th century of surprisingly energetic efforts to master and exploit the natural “resources” of Rakiuru, whaling, mining, seal fur trade, fishing and harvesting lumber, New Zealander’s finally left most of this southern island alone, so that ninety-eight percent of the island is under the management of the Department of Conservation (DOC). It is wild again, and feels that way. There are a few DOC huts scattered about, and a system of trails but most of the island is difficult to reach in any other way than a boat. Port Pegasus still has the remans of some of the settlements, rusted and covered in the bush, but arriving by sea it feels beautifully raw and untouched with very few visitors. We saw a few other boats, including Pazzo, who we met in Lyttelton. The fishing was ridiculously prolific. We caught something on nearly every drop of the jig, and it took less than fifteen minutes to have our first legal sized Blue Cod for tacos. All in all, a very special, wild, rarely visited place that was a little chilly from steady winds that certainly had a whiff of Antarctica on them.

Minerva North, Haven in the Pacific

Of all the places Allora has taken us, North Minerva Reef, is a stand out. The reef literally emerges only 90cm at low tide, and when walking on what feels like the Pacific’s very precipice, we had the surreal sensation that we’d been transported to another world. I urge you to read this article from New Zealand Geographic, which lays out the inherent hazards and contentious history of this fascinating ‘land:’

We, like many others, made a stop at Minerva North, to break up the often difficult passage between Tonga and New Zealand. Most boats poise themselves to try to stop, but the weather conditions have to be right to enter the pass and take the time in ‘pause’ mode as opposed to continuing onward, so we felt lucky to manage 3 days in the fold of the protected lagoon. We weren’t alone, though! The 30 boats at anchor around us were dubbed, ‘The Minerva Yacht Club!’

“Whales! One o’clock, Starboard bow! Not that far!”

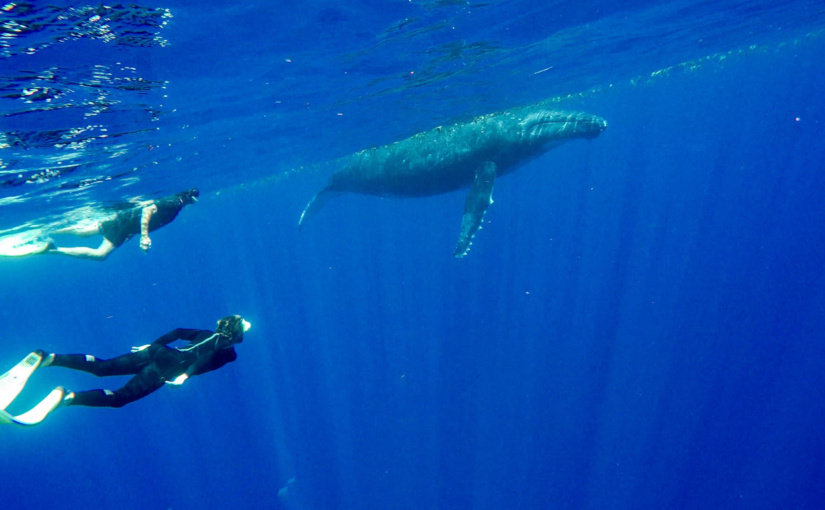

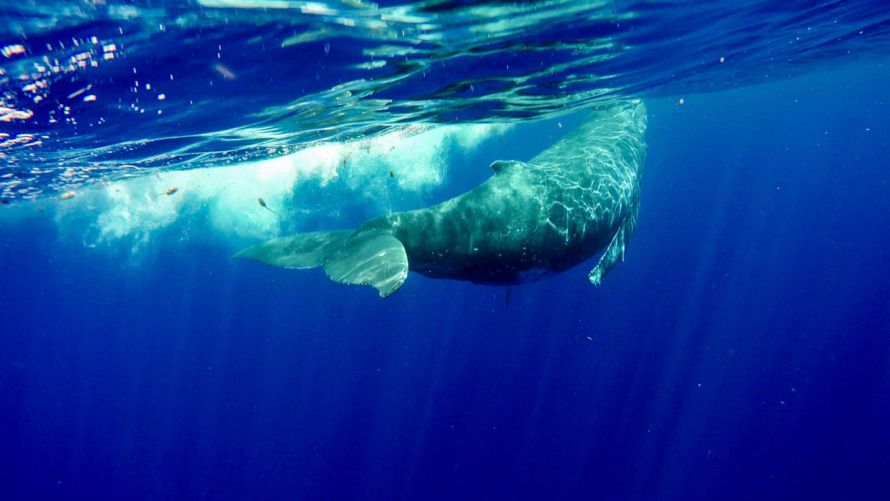

There isn’t much about humpback’s that you can get “used” to

fin and back slipping above the waves

scale inspires awe

flukes waving goodbye, whispering into the drink

surge of whales on the move

juvenile males on a mission

shouldering water ahead of them as they porpoise on the surface

strange knobby heads rushing through the foam

in calmer water, a spy hop, slipping up to peak at YOU

soft blow of a sleeping whale

the sudden totally unexpected wild audacity of a breach

that always always comes out of nowhere

and again

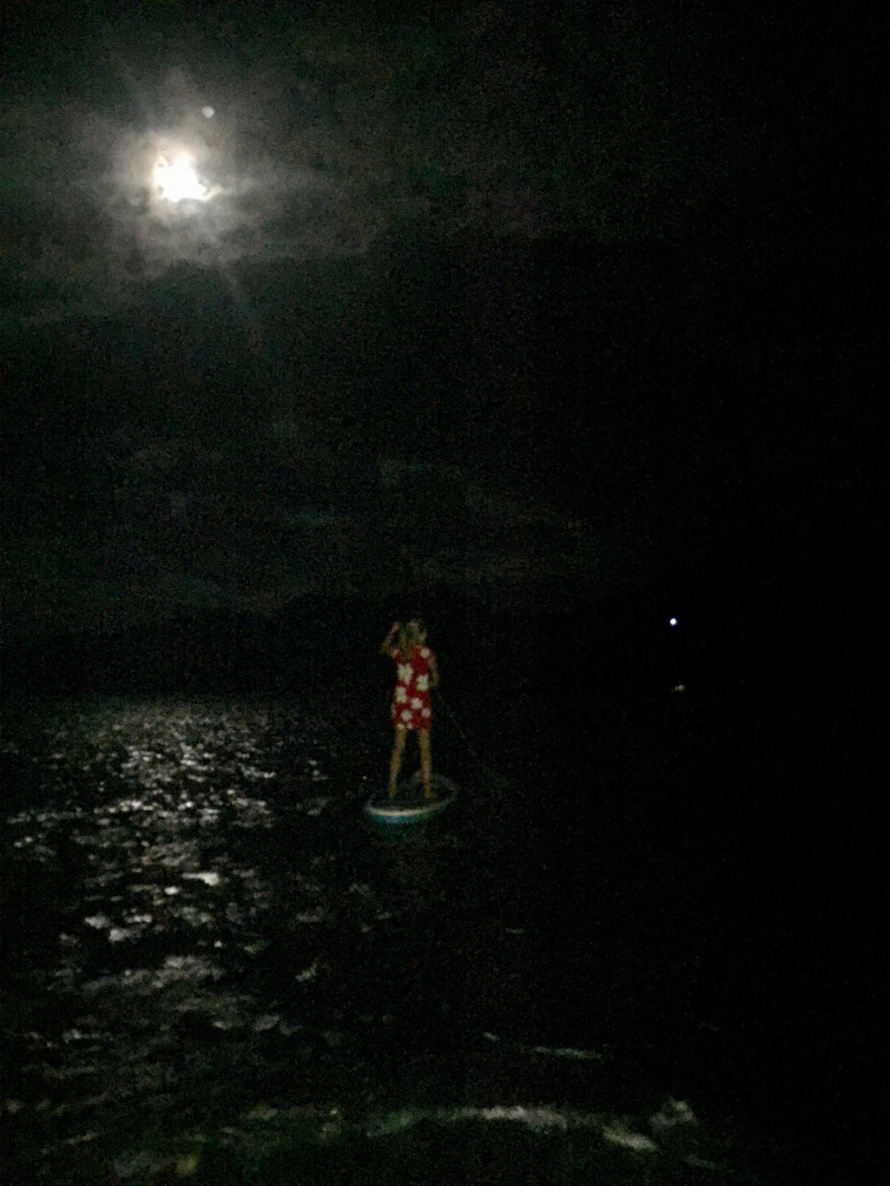

young whale under the stand up paddle board

gripping the camera, ready to go under

calves in the anchorage, sleeping with Mom

arced above her head

curious little ones spy hopping by the stern

or practicing their breaches

flopping, silly half out

then the day they show everyone what they’ve got

~MS

(Rough camera moves, sorry, but the proximity had us sufficiently EXCITED!!!)

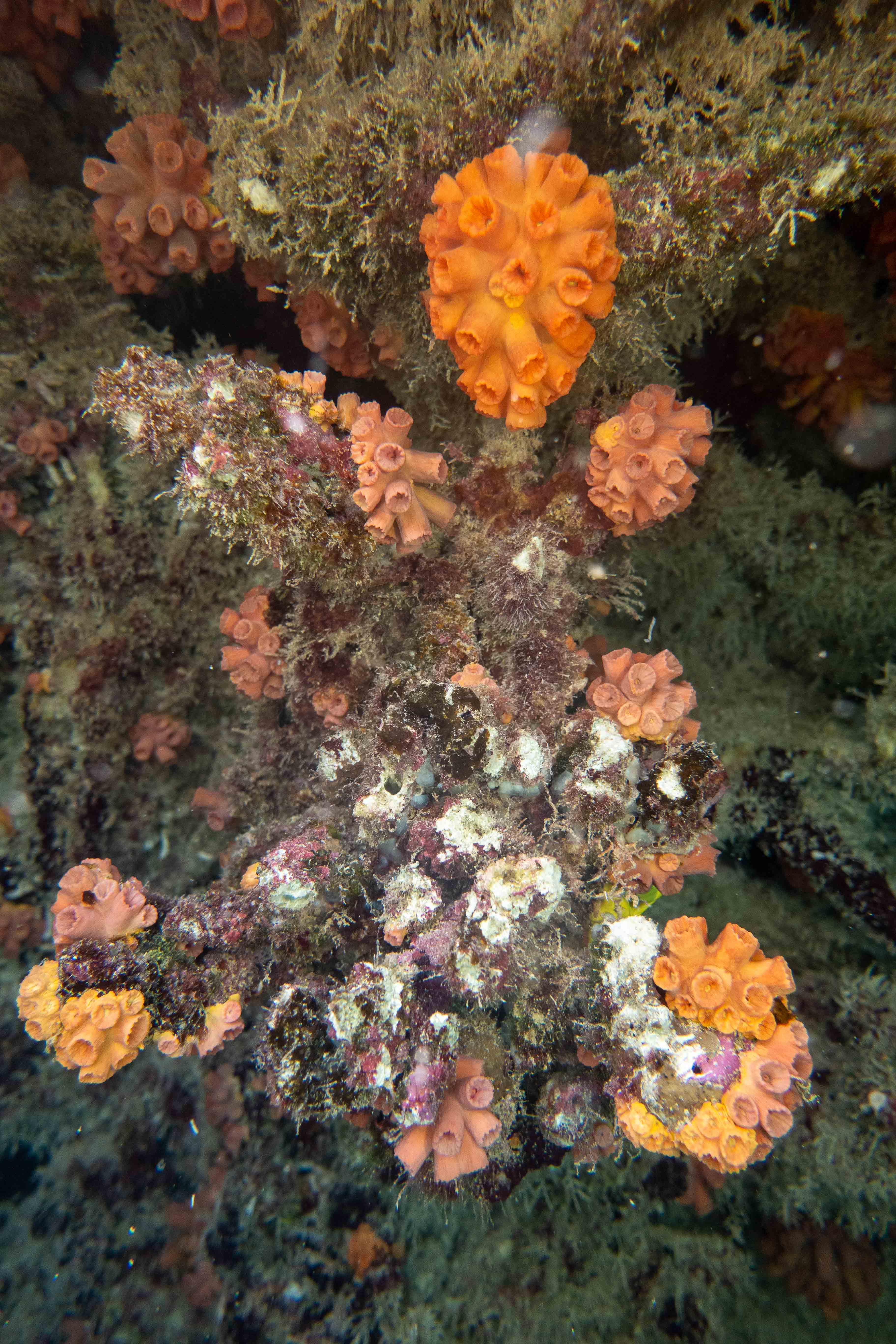

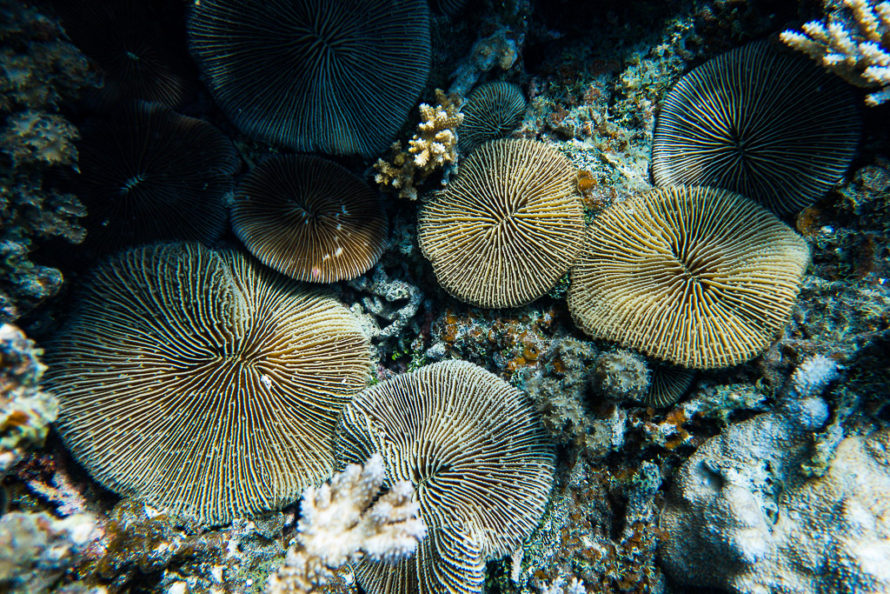

Penrhyn Underwater

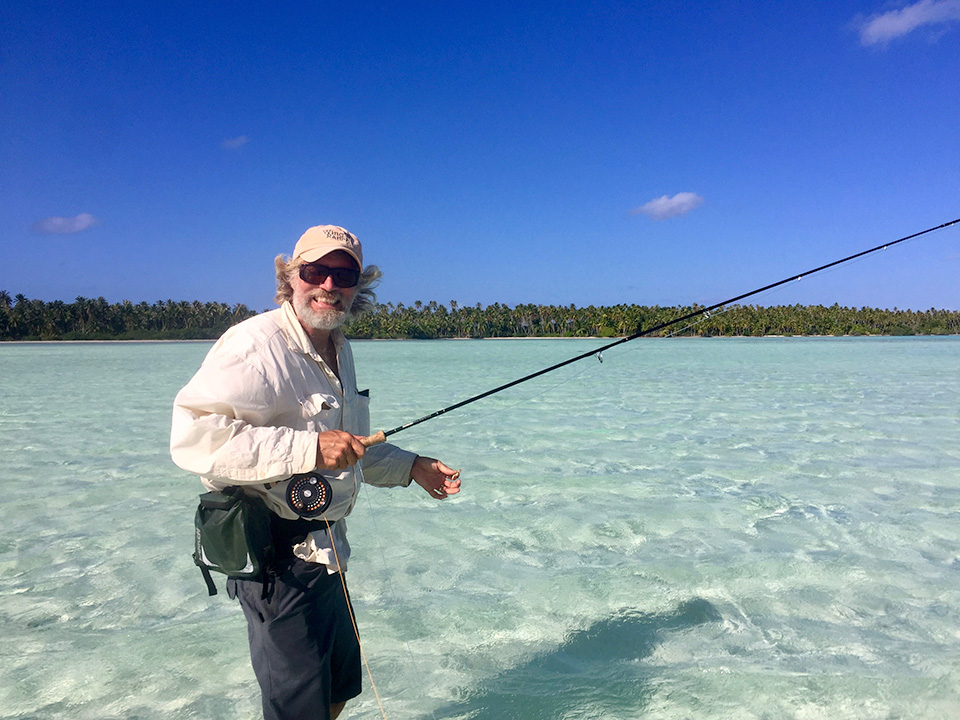

Mad for Kio Kio, bonefishing in Penrhyn

Every fisherman dreams about a secret fishing hole somewhere. Someplace no one knows about. No one goes. No one (or hardly anyone) has ever fished. A place where you show up knowing you won’t see a single soul and that the fish have never seen a fly. This dream fishing spot is naturally chock full of fish, too, everywhere you turn.

Every fisherman dreams about a secret fishing hole somewhere. Someplace no one knows about. No one goes. No one (or hardly anyone) has ever fished. A place where you show up knowing you won’t see a single soul and that the fish have never seen a fly. This dream fishing spot is naturally chock full of fish, too, everywhere you turn.

The Cook Island’s atoll, Penrhyn, might just be that place.

This atoll lays more than 800 miles of open ocean from anywhere. There are no flights. It is visited by just two supply ships a year. The only way to get here is in your own boat, sailing far off of the normal tradewind route. There was a time when expensive flights from the main islands of the Cooks occasionally brought an intrepid fly fishermen from New Zealand, though because there are no hotels or any other tourist infrastructure on Penrhyn the only way to fish these remote flats, even then, was to stay as a guest with the pastor at Te Tautua and have him take you. This apparently did happen at least once. Years ago. Basically, the only people who ever visit, in very, very small numbers are sailors. The intersection of committed bonefishermen and blue-water sailors who can actually get themselves to Penrhyn yields a very tiny slice of humanity. I’d bet there aren’t more than about five of us in the whole world, and that includes our friend Mike, who’s introduction to fly fishing was walking the flats with me in the Gambier and Rangiroa.

The pastor insisted on taking us to his spot, though we had our own dinghy and knew from Google Earth exactly where to go. Wishing to be gracious guests of the island, we accepted the ride. We spotted the first pod of fish even before getting out of the boats and over the next four hours (the limit of the pastor’s desire to stay and harvest noddy bird eggs), I landed at least fifteen bonefish (which is a lot of bonefish), considering the amount of time it takes to land each one and the fact that a fighting ‘kio-kio’ clears the immediate area on the flat of willing fish. Mike caught nearly that many, as well, and we were often doubled up with fish on at the same time.

We fished this singular spot for a couple weeks going back on our own, and it wasn’t always as good as the first day, the tide and the weather have a lot to say about how good the fishing is going to be, but it was always our spot and the fish were always there. They aren’t as big on average as the bonefish in French Polynesia, but Penrhyn is chock full of them.

We pinched ourselves regularly to make sure it was not just a dream. ~MS

Sweet Tuamotus, Last round through …

I’m going to ask Marcus to wax poetic about our final weeks in the Tuamotus. Suffice it to say that this region of French Polynesia is most definitely a favorite of ours and I even heard Marcus say he could live there. If fresh produce was available, I might be on board! For the time being, these pics can be a placeholder. These are shots from Tahanea, Fakarava and Rangiroa.

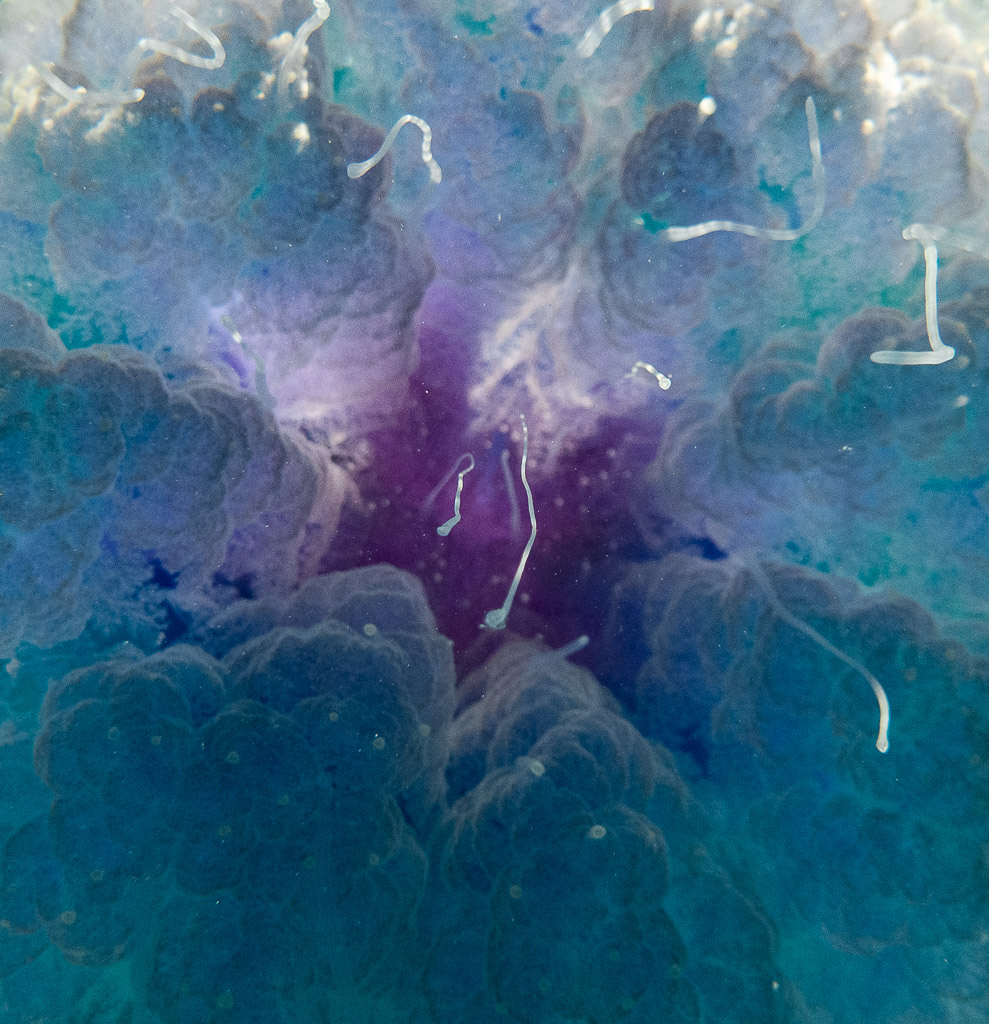

Cephea cephea/Crown Jellyfish

Tahanea, Tuamotus – April, 2019

We saw these dinner plate sized jellyfish while meandering around the SE corner of the lagoon searching for our anchorage. I hoped they’d stick around so I could get a closer look, because I could see that they were intriguing, but I HAD NO IDEA!! These shots were taken over 4 days of 15 -20 individuals. I was mesmerized!!! We were without wifi, so couldn’t even learn about the magic I was witnessing, but I was aware of being incredibly lucky to live on a planet where such a creature exists.

A quick search reveals a paucity of information about this jellyfish, but here’s a bit of what I found: Cephea is a genus of true jellyfish in the family Cepheidae. They are found in the Indo-Pacific and East Atlantic. They are sometimes called the crown jellyfish, but this can cause confusion with the closely related genus Netrostoma or the distantly related species in the order Coronatae. They are also sometimes called the cauliflower jellyfish because of the cauliflower looking crown on top of the bell.

Common Names: Crown Jellyfish, Cauliflower Jellyfish, Sea Jellies, True Jellyfish, Transparent Crown Jellyfish and Crown Sea Jelly

Scientific Name: Cephea cephea

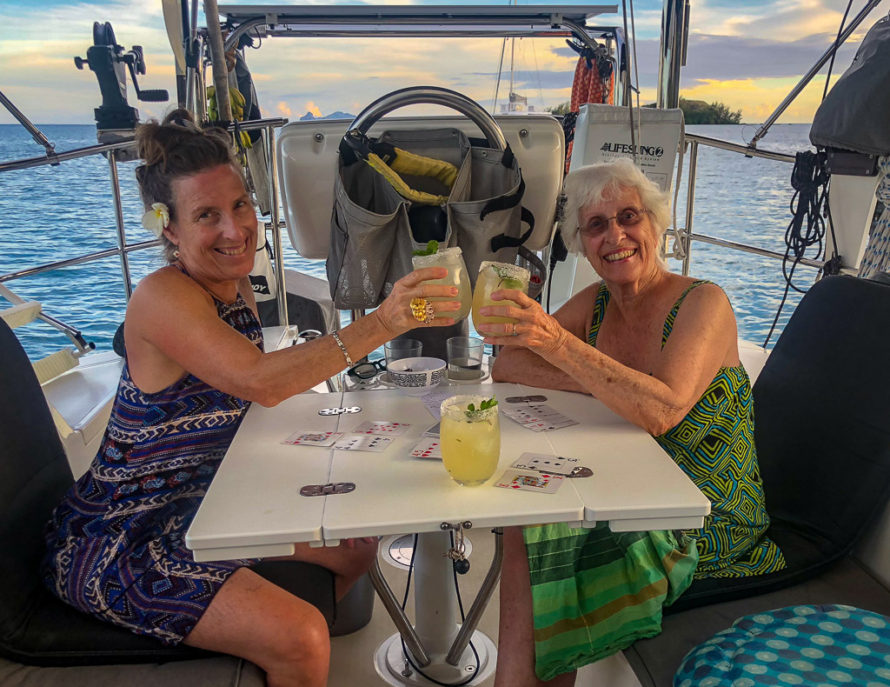

Elizabeth and Michelle, Mom/Sis team 2, Gambier!

cerulean seas

rain storm snorkel,

diving (with and without weight belt),

sharks, shells, sand, sailing in the lagoon

bugs on the beach, turtles

coconuts and an ancient village

Taravai petanque, ukulele and guitar

gusts from the mountain

anchoring pandemonium,

slow time and quick time

Valerie’s painting with sand

more fish more music

more fish more fish

damsels, butterflies, leatherbacks, grouper

parrot fish, sling jaw, guinea fowl puffer

canyons of coral, warm water

singing, laughing, lazy days

~MS

Mom and Lori team up in the Gambier!

Our 2019 ‘cyclone season’ in the Gambier kicked off with visits from our Mom’s and sisters. Mom and Lori arrived at the end of January and we enjoyed a couple of weeks aboard Allora, sharing our favorites (people and places) in this sweet eastern corner of French Polynesia.

Mom certainly knows her way around the boat, so she slips into very relaxed mode and we always marvel at her being ‘game’ to do just about anything. This was Lori’s first full-fledged stay aboard, so it was particularly wonderful to immerse her in our life afloat. These were full, rich days!!! ~DS

Through Lori’s Lens:

Through Wyatt’s Lens, Gambier, 2019

NEVER Too Many Whales!

Manta LOVE in Tikehau, Tuamotus

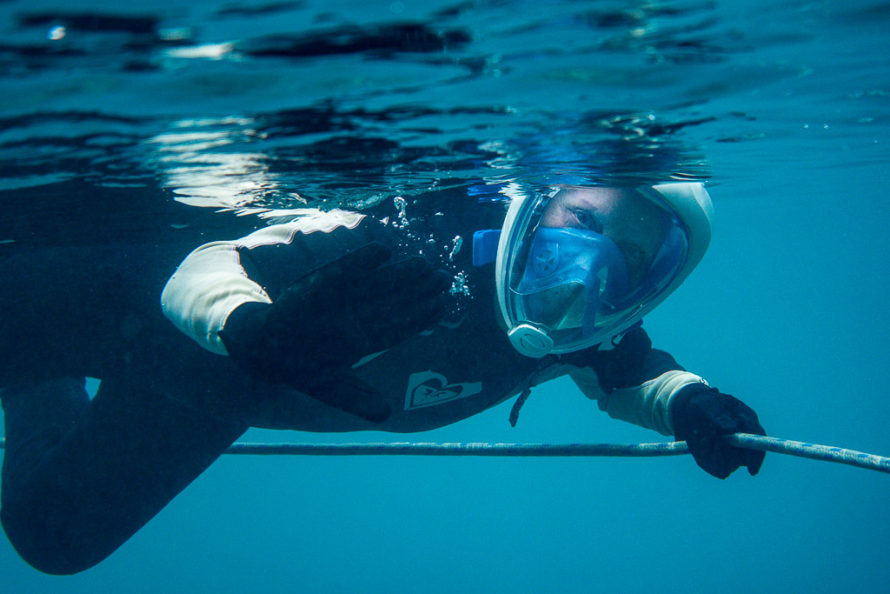

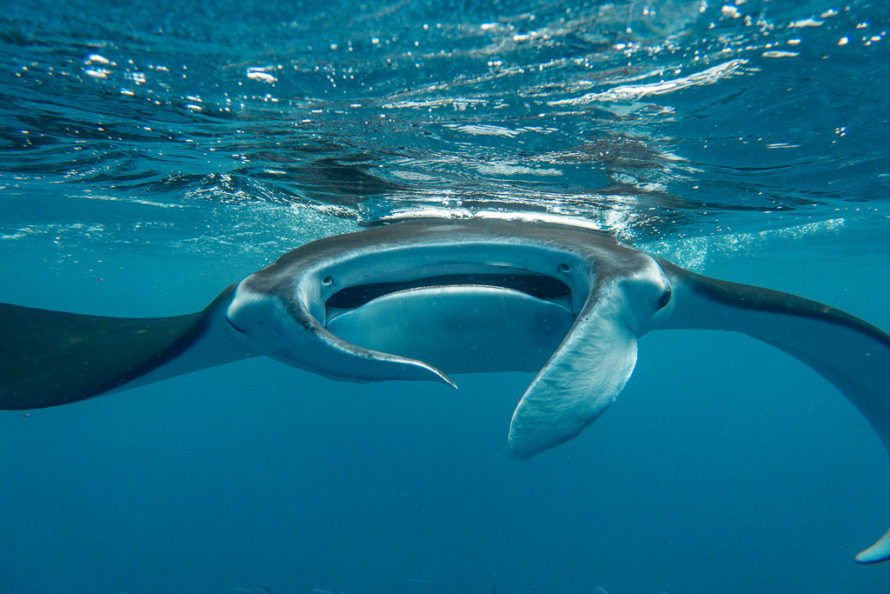

Pictures are going to do most of the talking here. Just think about the size of these amazing creatures, ten, twelve feet wing span (Manta Alfredi get up to 18’ across). Watching them move, like huge underwater birds, is mesmerizing. One bunch of six or seven literally bowled us over. You can find them in this spot pretty reliably because it’s a cleaning station. Diana was hooked. Another boat came to join us, Jacaranda, who we knew from their blog and got to know on the Single-Sideband radio net that covers this part of the South Pacfic (called the Polynesian Magellan Net, at 8173 USB, 0800 and 0600 local time). Linda is as crazy about looking for new fish as Diana, and she and Chuck had some amazing experiences hanging out with Manta researches on the remote island of Socorro in Mexico. I spent the morning writing, but Diana and her dive buddies got out with the Mantas early each morning. During one of their best sessions they watched a pair doing a courtship dance and then mating which is a rare thing to observe in the wild.

Diana dove with the Mantas twice a day for the week we hung out and took, you might imagine, thousands of pictures. Some of those she sent to an organization called the Manta Trust, (https://www.mantatrust.org) which uses the unique patterns of spots on a Manta’s belly to identify individuals. They encourage people to send in their photos, and then experts in each region identify and catalogue them. Diana sent them pictures of seven distinct individuals. Six of them had been identified before, and they shared some of the information they had from previous sightings, where when, doing what. One of them was brand new to the researchers. They told Diana that they have identified 70 mantas just in Tikehau, so now that’s 71. The next fun part, was that all seven had numbers for identification but needed names. So Diana gave them Polynesian names. Haley’s boyfriend suggested that ‘Liam the Manta’ would make a fine name, though inspiring a Manta name as that would be, it did not make the final cut.

Meet the Mantas:

Ma taa raara – (A shining, or bright eye)

Vavevave – (Speedily!)

Atae – (Surprise)

Marema re – (Sparkling as the saltwater at night)

Tamure – (Dance Together)

Atavai – (Elegant)

Manino – (Calm, Smooth)

Polynesian beauty with an Emperorfish. I brought the dinghy over to say hi and see what they were up to and she shared two fish with us for dinner.

Rangiroa -The Tuamotu Folks Have Heard Of

Our first instinct, on our initial pass through the Tuamotus last year, was to avoid Rangiroa. It seemed too popular – with actual hotels for tourists, including those ‘elegant’ thatched roof bungalows out over the water that plague Bora Bora. But on our second pass this year, we ended up spending a month in this largest of the Tuamotus atolls.

I’ll keep my part of the motivation for staying so long to one sentence: Rangiroa has the best bonefishing in the Tuamotus. Okay, moving on. Okay, well maybe not moving on. I broke both my nine and eight weight rods on these fish. I used up my entire stock of number 4 hooks. I fished everyday, and there were bonefish wherever we went, even at the touristy Blue Lagoon. We’re not talking armies of tourists, lets say a couple dozen for a whole day in three or four small boats. One group even waved me over and fed me lunch. The tour operator was an avid fisherman and pure Polynesian friendly. He told about a spot where he’d seen a giant bonefish, so big that at first he’d mistaken it for a shark.

Unfortunately, I never got over there. The wind shifted and we had to pull up anchor – which is a short sentence for describing a pretty harrowing situation where our anchor windlass failed, and we had to untangle the anchor from some nasty bottom, manually, and then with a little luck and jimmying of the windlass control, we raised the Rocna, just as the waves and wind built in earnest. Fortunately, we figured out the wiring problem at the next anchorage and it was an easy repair. ~MS

To Be A Dolphin!

I don’t know quite how to describe the magic of diving with dolphins. They played, they chatted, they rolled and swooped, they came over begging us to rub their bellies. We lost track of our depth and where we were. They came to see us two out of our three dives in Rangiroa’s Tiputa Pass. It was probably better the second time, because it was easier to slow down and take it in, rather than worry that they would only be there for a moment. It was wonderful to swim with them in their element, to watch one jump up out of the water, looking from below. In Baja we always debated which we loved more dolphins or whales (now there’s a silly argument), and it generally depended on which we’d seen most recently. I remember us saying, ‘dolphins, definitely dolphins’ once, and seriously just few minutes later a humpback breached out of nowhere and it was ‘whales, definitely whales.’ Guess what the sentence is now? ~MS

The wildlife of these remote atolls, which were originally called the Puamotus (poor islands) where lesser chiefs were once exiled, is addictive. It never stops. ~MS

Return to Paradise – French Polynesia

Fakarava North

Anyone watching us might have wondered what we were up to, bouncing back and forth between the anchorage off of Rotoava and a spot near the north pass of Fakarava. Part of the story is that you need winds with some north in them to be able to sit by the pass comfortably. There’s a nice public buoy by the channel marker and the snorkeling there is pretty awesome. Diana became quite familiar with its retinue of sharks and one particularly friendly triggerfish. I liked the spot because it’s a jumping off point for going to the far northwest corner of Fakarava. This is a nature preserve area, so no anchoring allowed. It’s about a five mile dinghy ride, but a pretty cool spot with some really nice fishing. Diana explored with me the first time, and I did the 10 mile round trip a few more times on my own. I brought a VHS radio in case I had any problems. Occasionally, a few boats brought tourists from visiting cruise ships to a place out that way they like to call the blue lagoon (every atolls got to have one). It’s a pretty spot and they bring lunch. I was lucky this time that they did, or not lucky depending on how you look at it. While I was off wandering across the endless flats in search of bonefish, one of these tour operators spotted Namo anchored by the shore of one of the motus. Apparently, he could not think of a single earthly reason that anyone would park a dinghy in that remote spot (not by the blue lagoon). So while I was out of sight, he “rescued” Namo and towed her away. It’s true that if one of the sailboats in Rotoava lost a dinghy this is where it would float to. Lucky for me there was still one other tour operator in the area, though it was a bit of hike to get to them. He was able to get one cell phone call out before he lost the signal, and after about an hour of chit chatting with the cruise ship passengers, Namo reappeared with the apologetic tour operator at the helm. ~MS

Toau

I think we’ve been to Toau four times now, maybe more. Diana’s posted about it before. The difference this time was that a new group of sailors was moving through, having done their crossing this year. It was interesting to see the island get new visitors, sailors who migrate through each year, visit the same spots, have barbecues on the beach, talk about their experiences crossing the big ocean, and think about the mysterious way the wind messes with the tides. There’ll be another group next year, too. We are so remote and still there is a steady presence. Toau is a popular spot, despite its tricky pass, for good reason.

Among the new crew were friends we made in Baja, Mike and Katie on Adagio. They have dive tanks and a compressor, so we got to do a little scuba diving. Mike is also a pretty fanatical fisherman and gets as excited about the subject as I do. He’d only been fly fishing once before, kind of on a lark in Yellowstone. But we grabbed a couple rods and went out a few times to see if he could hook one. Fortunately, he’s a good enough fisherman to understand that’s a pretty tall order for a first time, but he got a few shots, enough to get a fair idea of how addictive it can be. The fish were being tough in Toau this year, giving me a hard time, too.

We spent a little time on our own, too, doing what we do. Freediving to photograph fish, and yep, more fishing. Lots of water time.

We moved around to Anse Amyot, (the ‘false pass’ outside the atoll in the north), for a little more diving with Adagio, which was excellent, including some caves in the reef absolutely jam packed with sea life. I fished a little more. We bought some wildly overpriced lobster from Valentine, the snaky operator of the business there and had a wonderful lobster dinner with Mike and Katie. Valentine tells the story that she came to Toau as a little girl from nearby Arutua in a small boat with a two horse outboard. She says she was brought by her father to keep her grandfather from stealing her. She has his name, is the explanation. She’s been there a long time. She’s very, very religious. But she doesn’t seem particularly happy with her lot. There’s a defunct phone booth on the motu and a very funky pension. They installed buoys for sailors ($5/night) from the time there was a village here. This is the first place we’ve been where we felt this proprietary vibe, but the option to tuck in safely on the outside was sure nice. ~MS

South Pacific Moods

Last night with the moon just one day past full

you could see the sandy bottom and coral bommies in forty feet of water

chalky white like the moon

trade wind clouds shuttled gently overhead

and the surf on the reef seemed content and quiet

it’s good to be awake in the middle of the night

We are anchored in an atoll in the middle of the ocean

blue candy water

the haunting possibility of bonefish

Diana is not wearing clothes

when this winter front from down under passes and the wind settles back in again

what a beautiful place this will be

the passage down was textbook, two 180 mile days back to back

before the wind died for long enough to get a bunch of water made

and top off the batteries

arrived early to see the “pass” out of Raroia roiling like white water in Yankee Jim Canyon

When the internet is everywhere will all these remote places cease to exist

will they be like the color “dunia” of Otto-Raul’s Ten New Colors

undone by the ubiquitous web, always visible, available, knowable

Water makes us vulnerable to weather like nothing else

The wind swings and makes waves even in a protected lagoon

we put a lot of faith in our anchor rode

catching on coral rocks at the bottom

what does it take to break a piece of chain

if a pin works it way out of a shackle

everything we have could end up on the rocks

in a place too distant to recover it

Death by Coconut

Coconut palms are a funny weed to have so beguiled a species

they count as an invasive species here in the Tuamotus

a government subsidized invasive species

I guess so people have something to do, making copra

They are also incredibly dangerous

death by coconut is no joke

death by true love

is real too

you can keep looking up

but you can’t move fast enough

The stars above the motu shine in shrill dissonance

to conversations about digital apps

we are utterly dependent on GPS

and the stars wonder how they’ve become just window dressing

but nobody wants to hit a reef at night

the water sucks away from the cliff like edge and then hammers on like a threat

Kon Tiki wrecked here

Two boats sailed in today from the southern end of the atoll

tandem, tacking upwind in a light breeze

at a distance it looked like one boat

sailing as close as lovers, which it turns out they are

She eased her jib a little to fall back and follow

as they found a way through the coral heads

They moored to one anchor, one with a dark blue stripe, one light

tethered together with a boat length of line

He’s been single handing for six years

she wanted to learn

and when they met she’d already been looking at getting this boat

the same boat

So they sail together, she learning to sail alone

he’s not giving up on single handing,

since they are the same make of boat, they carry spares that work with each

on passage they can take turns watching each other’s boat sail by autopilot

watching for traffic and the hazards

they certainly have more space than they would with just one boat

no one has to climb the mast if there is an argument

but there are risks and downfalls to the arrangement

it’s much more expensive

if something goes on with the other boat, they can only help as much as they are able

they are still truly single handing

they admit that at some point they will move on to one boat

she says it will be hers

a point he is not yet willing to concede

Waterline Challenged (Lawsons, Maddi & Wyatt visit)

In August, we had the supreme pleasure of seeing how many loved ones we could fit aboard Allora without sinking her or going mad. Turns out it’s probably 7!

Actually, other than playing bumper bodies routinely and Scott slamming his head too many times, we managed well, sailed Allora, played hard and laughed a lot. It wouldn’t be called luxurious, but we had the sleeping spaces we needed and the Lawson’s were as mellow and relaxed as we could wish for. Wyatt and Maddi were here as well, both awaiting their Fall school starts. Those two can navigate Allora’s spaces and systems quite nimbly, so they stepped into their familiar ‘GREM’ role and really helped out. The coolest thing: with this group, we had a veritable band aboard! Concerts were spontaneous and the norm. In their absence, we truly miss the melodies.

Scott and Lori showered us with copious gifts, all useful and helpful, and we continue to be thankful, probably daily, as we make use of them. Sumner’s positive, can-do attitude was infectious; what a delight she is to be around – an ideal member of Team Allora. I treasured having Lori in my midst. Basically, we are already talking about when we can get these guys back. This voyaging life is extraordinary, but it is made even more so when we can share it with our ‘people.’ Come play with us!

Shadows In The Shallows

As we sailed south from the Marquesas, Diana was looking for sharks, calm lagoons protected from the ocean swell, turquoise water and coral, safe anchorage within earshot of the surf breaking on the reef. I was looking for flats — wide expanses of water that doesn’t rise above your knee in depth. Ideal for flyfishing. To reach the Archipelago of the Tuamotus, you sail by the Isle du Disappointment. We wished we had the time to detour, to see it for ourselves, if nothing else so we could say we’d been to the actual Island of Disappointment, but it was night when passed and low lying atolls are dangerous in the dark. We slipped by beneath the whisker of a moon.

Disappointment is a prerequisite for flats fishing. You must be comfortable in the waters of frustration. Particularly, if you go looking for fish that might or might not even be there. Bonefish inhabit the tropical oceans of the world, but they are not on every flat. And on the flats they do visit, they are not there every day. And when they condescend to haunt that ephemeral world, they come armed in ghostly mail, reflecting the dazzling world around them, barely visible. Liminal shapes. But you have to see them to catch them. You might spot a bonefish and she will turn and disappear right before your eyes. You will wonder if you have seen her at all. Often the only thing you can see is not the fish itself, but its shadow on the sandy bottom.

These atolls have long been known by sailors as the Dangerous Archipelago, and before GPS and Google Earth came along, most gave them a wide berth on the downwind run from the Marquesas to Tahiti. They get more visitors nowadays, but their isolation means that beside a select, well known few with air strips, the only practical way to visit is to sail there in your own boat. It took us twenty-five days to reach the Marquesas from Panama and another three days of fast sailing to reach the first of the atolls.

It’s a long way to go and nobody sails that far just to go bonefishing. Not even me.

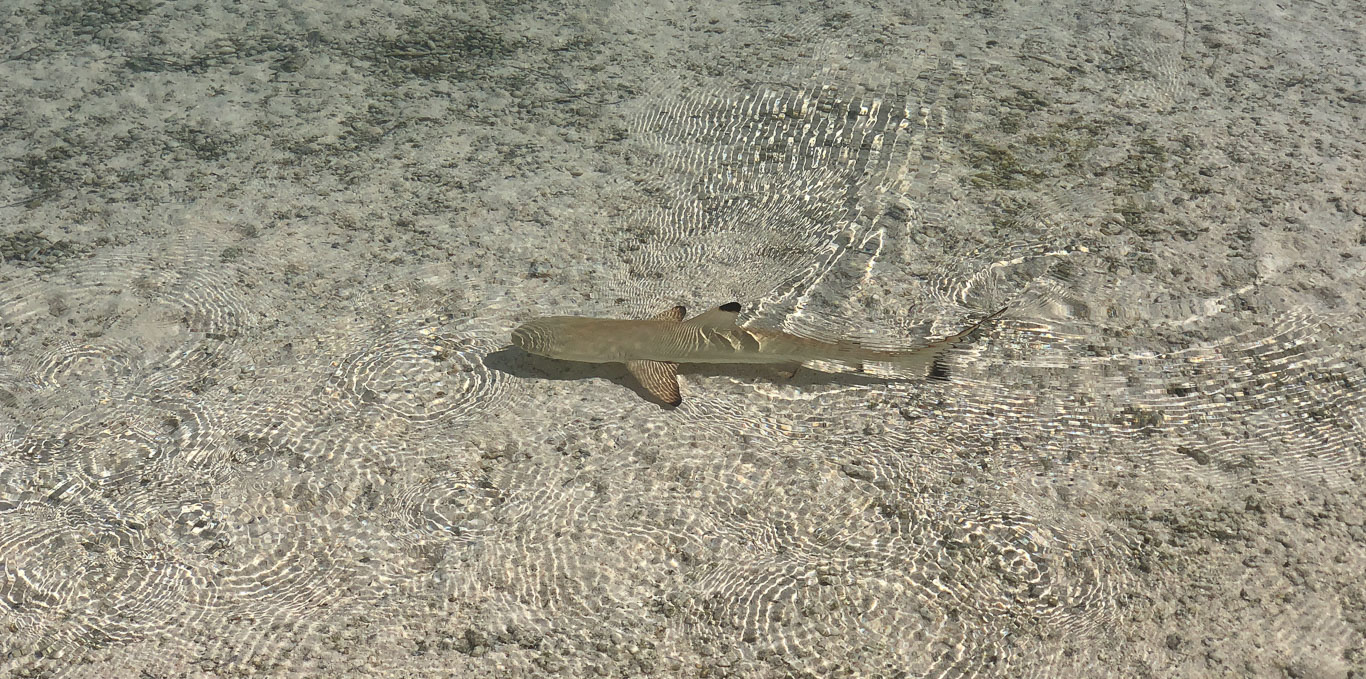

We chose the Raroia atoll as our first stop because it was the most windward of the Tuamotos that we could easily reach from the Marquesas. It also has a well known, well charted pass for entering through the reef. We had no idea what we might find on the flats there, and nothing in google earth showed up that looked like the classic sandy bottomed expanse you’d find in the Bahamas. I expected something like the gentle reefs of Turneffe flats in Belize, but what we found was not like either. The reef itself looks like a rocky moonscape when the tide is out. It is hard bottomed and the rocks and coral are viciously jagged. Near where we anchored, there were the rusted remains of a shipwreck, the massive engine block and parts improbably strewn through the shallow water. It was easy to imagine the churning caldron that this South Pacific reef would be in a storm. The surf breaking over the reef at high tide sent wavelets rippling over the flat and the current in the cuts reminded me of wading the Madison River. It was a live, active environment. It did not look like a place you’d find bonefish, and I did not.

What we did find, was first and foremost, sharks. Black tipped reef sharks make a fine living in the Tuamotos. As a top predator, they seem like the sign of a healthy ecosystem. The coral here teems with fish like an aquarium. The closest I could find to a “flat” were some sandy shallows on the lagoon side between the fast running Hoa’s (Tuamotan for the cuts in the reef). There were also lots of other fish, and I quickly hooked my first Bluefin Trevally which went screaming across the shallows just like a bonefish. It happened fast and was so easy, I initially underestimated this species. These crazy, nervous, spooky, wild fish have since put me in my place. Bluefin Trevally is a beautiful fish, and the couple that rushed in and grabbed my fly, as opposed to the dozen that bolted away at the speed of light when they heard the line hit the water, were as powerful as any bonefish, maybe a little less fighter jet and more raw power, but ripping into my backing nonetheless. One of the first I landed broke the tip of my new eight weight rod. I also caught some smaller blue jacks that were fun (one shadowing a shark), and a less than gorgeous but hard fighter called a Long Nosed Emperor fish. On Raroia, I found a version of flats fishing, but not bonefish.

I had read that we might find bonefish on Kauehi, another atoll due west from Raroia. A Montana fly fishermen (like myself) posted a short article about catching them there years ago. He and his wife had crewed on a sailboat crossing from Panama to Tahiti, and Kauehi is a natural, first stop in the Tuamotos. A beautiful island with a charming village, the seductive if elusive promise of internet at the post office, and baguettes on Saturday and Wednesday (a slightly chewy “wonder bread” version). This is one of the atolls with flights from Papeete.

I saw what I thought must be a pair of bonefish almost as soon as I waded out onto the town flat. But they disappeared quickly and soon I was questioning if that’s what I’d seen at all. It took more than an hour to find another pair. I blew the cast completely, trying to compete with 15 knots of wind. Now the question was if I’d get another chance to cast, or if I’d just botched a very rare opportunity. When I finally spotted the next fish, I forced myself to slow down and tiptoe quietly into a crosswind position and wait until I could make a short cast. It paid off, and I had my first Polynesian bonefish on, ripping way across the flat throwing rooster tails of water as it unspooled line like no tomorrow.

An old man (well, not that old, but with a gray beard like me) was taking a Sunday afternoon nap under an awning at the beach. With the southern winter trades, the temperature in the shade is perfect. I felt bad disturbing him marching across the beachfront of his idyllic bit of paradise, but he waved me over in that friendly Polynesian style, and I showed him a picture I’d taken with my phone of the bonefish I’d just caught on the flat in front of his house. He confirmed that they are called kio kio here and told me (in French) that they made excellent Poisson Cru, which is a yummy dish we experienced in the Marquesas, made there with raw tuna, lime and coconut milk. He didn’t seem particularly startled to see me out wandering around the two mile long flat near town, but when I asked Gary, the french dive master of Ephe Mer Plongeé, who’d been living aboard a sailboat in Kauehi with his wife and son for five years how often he saw people fishing out on the flat, he said, “Never. Nobody ever fishes out there.”

Obviously the locals do, I saw them come in with parrot fish and trigger fish they had harvested with a spear. So that’s not what Gary meant by nobody. He meant no off-islander with a fly rod. The young Polynesian man who showed me his spearfish catch, thought the triggerfish would eat my fly when I showed him what I was fishing with. And they did, though it wasn’t quite that easy, though certainly more than it must be stalking these skittish fish with a spear.

Fishing here is a way of life and it’s about food. It fits most people’s image of fishing — casting a baited hook into the dark water and waiting to see what you might happen to drag up. Flyfishermen are not that different from other fishermen, in most basic respects. Their attraction to the game varies according to the particular part of it that keeps bringing them back, the aspect of flyfishing that rewards and maybe also torments them. It’s like other games, like love even (yes, I did say that). For some size matters. For some it’s the battle and the conquest. For some it is the flirtation and the take. It’s first sight, the beating heart of the approach, the cast. The strategy and the plan. You only have to walk into any fly shop to realize that for some, it’s the fashion. For me, though there’s no doubt, it is true love, for all of the above.

A passion (or possibly an addiction) for salt water flats fishing, particularly bonefish, is something one comes to naturally as a fly fishermen for trout. It’s particularly seductive for a dry fly fisherman whose been bitten by the bug of rising fish sipping small dry flies in the gin clear waters of Montana.

Seeing the fish, stalking, presenting the fly. Precision. Timing. Delicacy. The take and the set. Those are the common elements of the game. A dry fly fishermen must remove himself from the fly, and any hint of current that might pull on the line, so the presentation floats naturally on the surface. The bonefishermen needs to learn how to move the fly the way the bonefish expects it to move, learning the timing of their body language to know when they’ve taken the fly and give them enough time not to pull it from their grasp.

Dumb luck will catch a certain percentage of fish anywhere. But it won’t work often enough to keep it interesting. If a game is too easy, it’s not really worth playing, right? On the flats, like so many things in this concentrated environment, mistakes comes fast and furious. Miss the cast, miss the set, break off. Bonefish almost never give you a second chance.

In Toau, the next atoll we visited, Diana saw bonefish swimming under the boat. In general they were concentrated closer to shore, probably because even though the flat is huge, most of it has three feet or more water even at low tide. Also, nobody lives here most of the time. The shallow edges go on for a couple miles. This atoll is one big step further away from the world. You cannot fly here. It’s only seventeen miles from one of the biggest and most populated atolls, Fakarava, so it isn’t that far. I saw the first pair before I really stepped into the water after taking the dinghy ashore. Another single within a few minutes after that. I landed the first fish within an hour of stepping onto the flat. Which was a nice start.

It hasn’t been non-stop like that, by any means. These fish aren’t easy. They spook at the line more than the fly, but they don’t like to hear it plop down. I started using a long tippet and tying my flies with lighter bead eyes so they can land more quietly. The colors that look right to me in this environment are tan with a touch of orange. It needs to belong but can’t be camouflaged — just sparkly enough to get some attention. They bead eyes are heavy enough to make sure it sets on the bottom which I think is crucial here, but not so big that they make too big a splash. In my previous iteration, I used ‘bunny fur,’ which I thought would be good for the splashdown, but I think it was too white. My final pattern used tan squirrel with 6 strands or so of iridescent flash. I caught 7 bones in total, six on this fly in less than three hours on the flat. I’ve been catching fish in water with no ripple on it, right up against the long beach, so I can watch them investigate the fly. Occasionally, they are pretty aggressive about grabbing it, but mostly they follow first, then take it only after it drops like it’s trying to hide. They seem to be used to the idea that whatever it is they are eating, shrimp or crab, is going to try to bury itself in the sand, not swim away. You really have to wait on the set. See them root down on it. They don’t take as long as the Triggerfish, which flop back and forth over the fly like they just can’t get ahold of it, and no wonder with that little mouth which looks overdo for a visit to the dentist. I try to resist casting to them now, because they almost always mangle or break off my fly, and I have a limited number of hooks in my fly tying kit. There are no fly shops for hundreds if not thousands of miles. That said, the other day I couldn’t resist, stupidly, casting to a grouper when I reached the rocks at the far end of the flat. He grabbed the fly in a dash and then didn’t seem to realize he had it, chasing away another small fish that had come out to investigate. I had to give him a tug for him to feel the hook and then he was off, straight for his favorite rock. After walking over reeling up all the line, I could feel he was still on, but I couldn’t pull him out from under the rock and eventually broke him off. After a bit he came out, the fly gone from his mouth, and glared at me like he was considering picking a fight.

Probably the most exciting thing about Toau bones is that sometimes I find tailing fish. It’s not like smaller Belize bones tailing in groups on the flat, these are pairs or big singles. Big tails. They don’t work a spot for very long, but they aren’t in a hurry either. I hooked a really big one in about eight inches of water. I was lucky because he was moving directly at me. Even so I spooked him and had to recast as he scooted along, now broadside. This time the fly hit the water in the right way and he turned to find it. The take was clear and obvious, an easy set. The fight was unforgettable. He was off at warp speed (of course) and ran toward the shallow without stopping until he reached the shore. Then he turned a hard one eighty. I started reeling frantically (as you do) wishing at that moment I had a large arbor reel instead of my classic old Abel. But nothing was going to keep up with this fish. I reached for the line to start stripping by hand out of desperation, and then jumped. This huge bonefish nearly ran me over in his panic. I still had backing out, and he was zinging past my feet. I assumed he was long gone, but then he hit the end of the line, still on, and turned on a rocky shallow spot. Some poor fish there leapt skyward to get out of his way as he ripped across less than six inches of rock strewn water and in a second it was finally over. Somewhere the tippet had found a sharp piece of coral.

Day 3 on the Toau flat, I think (nice to be losing track), the fish conspired to humble me. My first big theory that it would be good to have low tide in the middle of the day turned out to be exactly wrong. Despite great visibility, and probably because of it, I did not see nearly as many bones. Fewer sharks even, until the tide started to come in as the sun dropped. After three thirty it gets hard to see at any distance except over by the shore where the windless water reflects the darker trees. I finally landed one fish out of a pair, but before that, it was either, wrong time, wrong fly, wrong cast, wrong presentation. They followed but would not take. I could see their eyes as they came in that close, but they wouldn’t pick the fly up.

With their 3D world reduced to two dimensions, and the sun a glaring light, Trevally are a nervous wreck in shallow water. They don’t know what they want to do. They cruise at high speed looking for an ambush with none of that sharklike cool. When they blow up at the slightest provocation, they streak away and then seem to worry that they’ve made a mistake and streak back in to see what they’re missing, then blow up and away again. They dart at the fly as if they know they are making a mistake. I cast to a pair of Trevally cruising inches off the beach and they left so panicked, I think they moved to the next atoll. But then later, I was able to get a cast fifteen feet in front of a pair coming toward me, a little further off. The first fish charged the fly from that distance so fast I have no idea whether I was stripping or what I was doing, but he was on! Another Trevally half an hour later startled me by bashing something under the ledge of the coral right at the shore and then came racing out my way. I cast to him, but I don’t think he saw the fly. He was too busy looking right at me.

I guess I have been a little skittish on the flats, too, and maybe for the same reason. There are always lots of black-tipped reef sharks everywhere I wade. Curious as cats, with (presumably) bigger teeth. Early on, two of them, inspired by my splashing in shallow water charged in and hit my leg. Unnerving to say the least. Several others came swimming in at high speed, and finally I ended up bumping one six footer on the head with the butt of my rod to stop it. So there it is, full disclosure, there are lots and lots of sharks in the Tuamotus. I started carrying a walking stick for discouraging sneak attacks.

8:30 is about as early as the light works. The water feels cooler in the morning, but I think the light is more significant. These bones seem to stick to the very skinny water and so when it’s straight overhead they are skittish or not around. I saw more bonefish early, including tails. But I was having trouble getting the sequence of things right. Fish headed the right direction. Cast close enough, but not too close. Fish seeing fly but not spooking because it’s moving too fast. Timing right on the set, not too soon, not too late, not too quick, but quick enough. Tight line on the fight, keeping fish away from any rocks. Landing and releasing the fish without alerting any of the bigger sharks. It’s a long list. I headed back a little later than I had planned, around 10:30, Cast, hooked, landed two fish on the way back. The sharks found me after releasing the second one. I thought the bonefish must be okay, but the bigger shark, darker in color was very aggressive in swimming directly up to me. I think he could smell the bonefish in the water about me and he was sure he would find it at my feet or in my hands. I still don’t think he would bite me unless that bonefish was actually there and he could take it from me. That might be a different story. Though, I told myself, since evolution would not have designed them to bite human legs, standing ones anyway, I wonder if he would or even could be able to turn sideways in the shallow water in order to take the bite. So maybe he couldn’t bite my leg even if he wanted to. These are the kinds of things you think about on a Polynesian flat. I had to beat the water with my shark stick a couple times and then it tore off. I assumed it was because I had taught it a lesson about messing with a stick carrying member of homo sapiens. But then he started zig zagging at high speed. My heart sunk. He was chasing something. What’s truly astonishing about these sharks is how far away they must be able to sense a panicked or tired bonefish. Somehow they know the fish are too fatigued to outrun them. I’ve seen them working the flat where I’ve just released a fish like bird dogs in Montana.

Because of the couple of sneak “attacks,” I’ve developed the habit now of turning all the way around ever so often to make sure I’m not being stalked. It seems like a good idea anyway. On a flat, unlike a river, a fish could be coming from anywhere. One of the things I’ve noticed is that sometimes there’ll be a couple of nervous blue jacks following my mud trail. I think the sharks come from that direction for the same reason. They investigate all anomalies on the flat. You (if you are a shark) never know. This time about twenty or thirty yards behind me at the end of the faint trail I was leaving in the sand was a bonefish following me. I turned and made the short cast to an easy fish. He tailed on the fly nicely. Now I was sure that this new fly pattern, which had evolved from my short experience in Toau and in Kauehi, was the perfect Polynesian bonefish fly.

Day five on the Taou “town” flat. We explored “town” today. So far what we can find are the remains of a half a dozen structures. There are a couple of hard hats around that must be for the safety of working in the coconut groves, but the shacks are falling down. This was my most successful day fishing so far. The High tide was 6:52 and low tide was 13:06. I didn’t leave until 10 because we spent the morning doing some boat work. I scooted off, guiltily, leaving Diana finishing the job, cleaning oven parts on the stern. As soon as I started toward the flat after tying up Namo (our dinghy), I came upon two Trevally working quickly up the beach, as they do, not two feet off the edge of the water. I moved up the bank and walking as fast as I could without running I was just barely able to catch and pass them. I kept moving until I had time to get down to the water’s edge and strip off enough line for a cast. I made the cast at least ten or fifteen feet short, so I could move the fly when they got close. Even at that distance they reacted at the speed of light. My thought process barely had time to catch up with what was happening. They spooked right? Even with plenty of wind to hide my line noise and even casting way ahead of them. They are so hyper sensitive, they just blew up. No way to catch them in this scenario. Except that… my body was moving ahead my conscious thought process, and I stripped out of habit. And, unbelievably, a fish was on. Besides sailfish in Mexico, these are the most beautiful fish I’ve ever caught (okay, maybe not the mug, which is a little dopey) but the coloring is spectacular. The second Trevally did not abandon his buddy for a good part of the fight and I found out when I landed him that these Bluefin do have small teeth, like a brown trout.

It was a nice start and it got even better but then worse. I had barely waded onto the flat when I spotted a pair of bonefish. They were moving slowly enough that they were clearly looking for food. When I’ve cast to fish here that are really moving across the flat, they spook, or if they follow I get a refusal. These fish were in 6 inches of water. Really. I was lucky with my cast. The wind subdued any line splash down, and the fly went into the water without too crazy a plop. The one fish turned on it followed and took the fly without hesitation. Because I didn’t want to lose the fish to a shark and because I knew my tippet was stout, I pressed the bonefish pretty hard and when he was close I leaned heavily into the rod to get his head up and bring him in. I slipped the barbless fly out of his mouth and as soon as I let him go, I noticed what had happened. I had broken my rod tip. I’d already broken my eight weight at Raroia on a Trevally (also no spare tip, yes I’m that foolish). Looking at the tip of the rod was a lot like looking at the water when you’ve dropped some crucial boat part overboard (like the oil drain plug on the outboard for instance). Something you can’t just replace with a clever substitution. You just can’t believe that something so irrevocable has happened so quickly that could have such major consequences. The most immediate consequence was that I had to stop fishing after a late start with low tide just two hours away. I had one more rod. An eleven weight, which was going to make delicate casts a challenge, but at least, I had something to fish with for the next two weeks before the Lawsons, Maddi and Wyatt meeting us in Tahiti could rescue me with spare tips.